Enrique Chagoya

Mexican, 1953- (active USA)

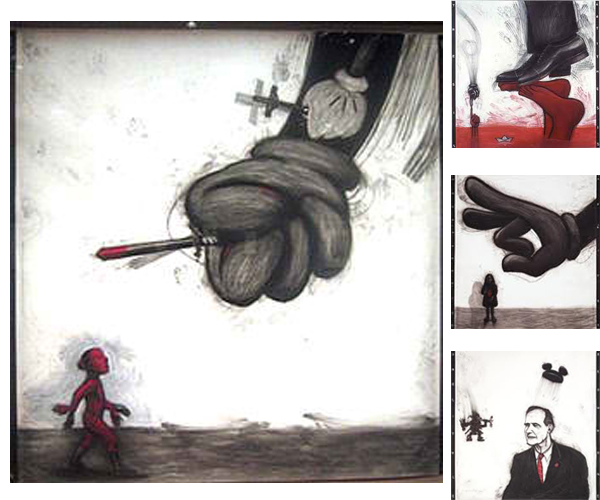

1942, 1989

charcoal and pastel on paper

80 x 80 in.

SBMA, Museum purchase with funds provided by SBMA Friends of Contemporary Art

1996.7

Undated photo of a youthful Chagoya

“My artwork is a conceptual fusion of opposite cultural realities that I have experienced in my lifetime. I integrate diverse elements: from pre-Columbian mythology, western religious iconography and American popular culture.”

Enrique Chagoya

RESEARCH PAPER

THE ARTIST

Enrique Chagoya was born in Mexico City in 1953. His father, a bank employee by day, and an artist by night, encouraged his son’s interest in art by teaching him to sketch at an early age. Chagoya credits the nurse that helped raise him with his first exposure to the culture and history of the Mexican indigenous peoples. As a young adult, Chagoya enrolled in the Universidad National Autonoma de Mexico, where he studied Political Economy and contributed political cartoons to union newsletters. He then relocated to Veracruz and directed a team focused on rural development projects. He describes this experience as one that “made me form strong views on what was happening outside in the world”.1 This growing political awareness would later surface in his art. At age 24, he immigrated to the US and settled in Texas. After working as a union organizer he moved to Berkley and worked as a graphic designer. He then enrolled in the San Francisco Art Institute, where he earned a BFA in 1984, and later went on to earn an MA and an MFA at UC Berkeley.

He is currently an Associate Professor at Stanford University’s department of Art and History, where he teaches painting and printmaking, and his work can be found in many public collections.

Being from both Mexican and American cultures, Chagoya uses popular and religious symbols to express complex issues of colonialism, and oppression that portray the historical and contemporary issues of these two clashing cultures. He most identifies with the Spanish painter Goya, and sees himself, like Goya, as expressing and reacting to his time with dreamlike, unconscious imagery. Chagoya describes his art as an “integration of diverse elements from pre-Columbian mythology, western religious iconography and American popular culture.”2 He believes that these diverse images collide and synthesize in the viewers mind.

In a 2000 collaborative book of images and montages that was inspired by pre- Columbian codices, the Codex Espangliensis, Chagoya illustrates the colonial conquest and cultural transformations that have formed the Americas from “Columbus to the Border Patrol”. In this work, he expresses that history is told by those who win wars, and that he uses “contemporary action figures and cartoon icons to stand in for the cultural imperialism perpetuated in commercial as well as political realms. Superman, Mickey Mouse and Wonder Woman join in a visual history of political oppression and exploitation that is both violent and seductive.”3 Chagoya holds that cultures are successively transformed and or destroyed by conquering cultures that destroy the previous cultures written history. They then re-write it from their point of view. He believes that the conquest of the Americas started in the late 15th Century with the destruction of the written history of the ancient cultures. He often uses blood and bloody bodies in his works to represent the slaughtered indigenous peoples, and uses the hands and fists of cartoon superheroes to symbolize both the colonization and Catholic conversion on one hand, and suffering and martyrdom on the other.

THE ART

Enrique Chagoya’s bold charcoal and pastel work on paper, “1492”, executed in 1989, is a prime example of his art that expresses his unique artistic and political vision that has evolved from living between two cultures, his early exposure to indigenous Mexican culture, and the historical roots of that country. It also clearly expresses the centuries old imbalance of power between the colonizing cultures of Christian Europe (Columbus in 1492), the current (1989) U.S.’s cultural imperialism, and the indigenous peoples that preceded them. Titled after the date that Columbus discovered the Americas, Chagoya juxtaposes a red indigenous figure that looks to be casually strolling on an empty plain, about to be slaughtered by two ominous fists. There is an “E” on the sword that is most likely a symbol for Espana (Ferdinand and Isabella) that funded Columbus to discover the New World. The largest fist holds a bloody sword, suggesting the violent subjugation of the Mexican natives by the Europeans in the 16th century. Behind that fist is a smaller, cross bearing fist of the ubiquitous Disney icon of Mickey Mouse that suggests the later oppressive influences of Catholicism and the economic and cultural imperialism of the U.S.

The work is on paper with two bold black lines that line either side of the subjects, and the numbers 1, 4, 9, and 2 are in the corners of the piece. The use of paper gives a fragile look that contrasts with the bold figures on it. The numbers that title the work, frame the action, and seem to frame it in time, and history. The use of charcoal and pastel, on the fragile paper, give the work a rough, earthy feeling. Perhaps this is Chagoya’s feeling about his native country. The only color in the work is a dominant red that is both the indigenous figure’s (Indian) skin, and the red blood on the sword and fists, that probably symbolizes slaughtered, and martyred peoples.

Upon first viewing, the red figure is the focus; an innocent in peril. A closer look reveals a human mask and four arms and hands that let the viewer know that it is Xipe Totec (Shep-eh Toe-tek), the pre-Aztec “flaying” god of Spring and fertility. He was a golden god with little skin who flayed a human being and wore his skin over his body for protection. He is most often portrayed as wearing the face and the skin of a flayed victim whose hands can be seen dangling below his hands. In worshiping this god, the Aztec priests yearly sacrificed a human by removing his heart, flaying him, dyeing the skin yellow, and wearing it during their ceremonies. The god underneath represented Spring, re-growth and fertility. The skin was the “new skin” of Spring, and dripping blood was the fertile Spring rains. The Aztec empire in early Mexico was a violent, conquering culture that sacrificed the conquered humans to appease their gods. It was predicted to Montezuma, the ruler of the Aztecs, that a light god, in the form of a “white bearded man” would overthrow him. When the Spanish under Cortez arrived in 1519 the empire was overthrown, thus ending the Aztec empire. In this light, the larger fist could also represent this conquest of the Aztecs.

There is a strong theme of human hands in the work; the dominant, aggressive cartoon fists, and the four hands of Xipe. These are both symbols of mans’ historic primitive aggression with the use of his most primitive weapon, the human hand. The fists in the work are accented with fingerpainted lines that imply movement in the air, but also suggest smeared blood. This theme is further developed by the placement of numerous faint handprints to the left of the fists, leading upward above Xipe’s head. Perhaps these prints show the other side of mans’ primitive aggression. They are possibly the bloody hands of suffering martyrs and innocents who have been sacrificed throughout the ages in the violent successions of dominant cultures. The movement upward of these hands is like a succession of souls of slaughtered innocents moving toward heaven. Finally, the human hands in the piece are those of the artist, Chagoya, caught between two cultures, and caught in the succession of dominating cultures today. He is part of both the dominating and dominated cultures, using his hands to express a facet of the human condition.

Thus, in what looks to be the story of an innocent native about to be sacrificed by avenging cartoon gods, a deeper inspection reveals the history of conquering cultures in Mexico. This work is the moment in history, 1492, that marks the entry of the Western Europeans into the New World that leads to the successive conquering and cultural transformations of the cultures that came before them. The work also makes a broader statement by Chagoya about the political, economic and psychological nature of man’s need to conquer and control weaker peoples.

In conclusion, Chagoya, with bold, dreamlike symbols, and a simple palette of colors, depicts the history of the Mexican culture from the Aztecs to today. He uses the pre-Columbian god, (Xipe Totek), the symbol of Columbus, (a bloody “E” sword and cross), and the post Columbian image of the U.S. (Mickey Mouse) to depict the subjugation and colonization of the indigenous people by a succession of violent, religious, and imperialistic cultures in the Americas.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Paul Guido, 2006

Footnotes

1. Chagoya, Enrique. Quoted in Steven Nash, Borders of the Spirit,” Triptych

(October/November/December, 1994) 24.

2. Chagoya, Enrique. Artist’s Autobiography. Online. Stanford University, Art and Art

History Dept: 2/22/05.

www.stanford.edu/dept/art/people/bios/chagoya.html

3. Guillermo, Gomez-Pena, Chagoya, Enrique, Rice, Felicia. Codex Espangliensis; From

Columbus to the Border Patrol, City Lights Books, San Francisco, 1998

Bibliography

Blackwell and Blackwell, Mythology for Dummies, Wiley Publishing, 2002.

In the Docent Files, and file in Museum Library:

1. KQED/Public TV: Spark: Enrique Chagoya

www.kqed.org/spark/artists-orgs/enriquecha.jsp, 2/22/2005

2. Manuel, Diane, The Prince of Darkness and Light. Stanford Today, Jan/Feb, 1997.

3. St James Guide to Hispanic Artists, Farmington Hills, MI: St. James Press.2002.

Provenance Materials, Bill of Sale of work from Gallery.

Acquisition Committee, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Paule Anglim Gallery, San Francisco, 2/13/96.

E mail from the artist to Paul Guido. February 12, 2006.

Xipe Totek

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xipe_Totec

www.britannica.com/eb/article_9077691

www.latinamericanstudies.org/xipe_totec.htm

Undated photo of Chagoya painting at desk

COMMENTS

The three additional images (above right, not in our collection) are from the same time period and series, as the SBMA’s 1942. Two were included in the Des Moines Art Center’s exhibition, Enrique Chagoya: Borderlandia, a 25-year survey of the Mexican-born, American artist, September 21, 2007 through January 6, 2008.

The wall text that accompanied them:

Editorial Cartoons

Chagoya first exercised his artistic free speech in the large-scale, charcoal and pastel political cartoons from the mid-1980s to early 1990s. These mark the Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush years, when the conservative Republican agenda resulted in perceived setbacks in civil and human rights and, arguably, initiated censorship in the arts. Like Spanish master Francisco Goya and Mexican popular artist José Guadalupe Posada, Chagoya uses a dark humor to deliver his political criticism. Invoking the familiar and adorable Mickey Mouse-by gloved hand, mouse ears, or full costume -- Chagoya introduces the reality of the friendly face that disguises a powerful administration or corporation.

Thesis / Antithesis, 1989

Tesis / antítesis

Charcoal and pastel on paper

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Gift of Viacom and Bravo, the Film and Arts Network

1994.87a-b

A red and black palette dominates much of Chagoya's work. In Aztec culture, the color combination symbolizes duality and the interdependent nature of opposites. A basic structural element of Mesoamerican religious thought, this dual concept holds a place in numerous cultures, including the yin and yang of Chinese philosophy.

As indicated by its title, Thesis / Antithesis presents a selection of paired oppositions: black and red, civilized and natural, clothed and naked, right side up and upside down, above and below, air and water, gloved and bare-handed, shoed and barefoot, hand and feet, and sky and air. The synthesis of the opposites in the image takes place in the mind of the viewer.

When Paradise Arrived, 1988

Cuando el paraíso llegó

Charcoal and pastel on paper

di Rosa Preserve, Napa, California

The giant gloved hand of Mickey Mouse appears poised to flick an innocent Latina girl (with a radiating halo and bleeding heart) out of the picture. Across the middle finger, the words "ENGLISH ONLY!" are written, referring to the 1986 California referendum that made English the official language of the state-a harsh blow to the bilingual education laws that had assisted in the assimilation of a huge population of immigrant children to the Untied States. Chagoya's exclamatory text confirms the contempt shown toward minorities and immigrant populations by the dominant powers of U.S. corporate culture-here exemplified by Disney with Mickey's giant, gloved hand.

http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/7aa/7aa840.htm

One Little Brown One, 1989

Auction: Bonhams -May 2, 2011 - San Francisco

Charcoal and pastel on paper

79 1/2 x 79 ½”

Description: Gift of the artist to Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco, California

For: “Art Against Aids Charity Auction”, San Francisco, California, 1989

(Sold for US$ 7,930 inc. premium)

Private Collection, Northern California

LG 2012