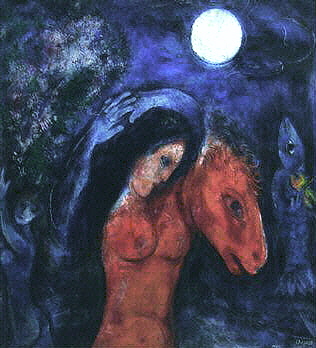

Marc Chagall

Russian, 1887-1985 (active USA, France)

Horse-Woman (Femme à Cheval), 1945

oil on canvas

32 5/8 x 29 1/2 in.

SBMA, Gift of Dwight and Winifred Vedder

2006.54.4

Photos of Virginia Haggard-McNeill with Chagall, and Bella with Chagall (above right).

'My art is an extravagant art, a flaming vermilion, a blue soul flooding over my paintings.' - Marc Chagall

RESEARCH PAPER

At first glimpse Chagall’s “Femme à cheval” (Horse-Woman) dazzles us with its two vibrant primary colors: vermilion and deep blue. The two central heads bent down looking in the same direction also draw us in. Then, as we come closer, much more is revealed: the two heads, that of a woman with long black hair and that of a red horse stem from one red female body. That nude female body is very present in the foreground. Her raised arms form like a halo around her head. From this nocturnal world lit by a cold white full moon emerge unexpected, but not unfamiliar forms: on the right a fish plays the violin, from behind the moon one guesses an upside down horse, and finally, on the left, a young woman, also nude, holds a huge bouquet of flowers.

All these elements (the red horse, the double headed hybrid figure, the flowers, a creature–whether human or animal, playing the violin) have appeared in Chagall’s previous works, but not in this grouping. We know that in all his paintings, there is a subtext, a personal narrative that often remains ambiguous because the storyline is charged with his emotions, his subconscious, and his past. A certain melancholy pervades this scene, but there is also music and flowers! Chagall is on the point of starting a new life.

Horse-woman, a transition work

We are in 1945, in New York, Bella, his first wife and great love, had died very suddenly the year before. Chagall is totally distraught by the loss of his companion, his lover, confidante, and advisor. “All is darkness”, he said. For several months, he does not touch a paintbrush and all his paintings are facing the walls. Bella, like him, was Jewish and from Vitebsk (Belarus). They had left Russia because his Communist colleagues no longer appreciated Chagall’s work and he did not like the direction Modern Russian art was taking. So, in 1923, after a year spent in Berlin, he returned to Paris with his wife and daughter. He had previously spent several years there (1910-1914) to develop his art, when a young man. That final departure from Russia was their first exile. Then, in 1939, the Nazis invaded France and they had to face the risk of being sent to death camps. In early1941, after being arrested and released, he finally accepted to leave France, his second homeland. Thanks to the help of Varian Fry and an invitation from MOMA, they were able to take refuge in New York. This was the second exile. He saw himself as “the wandering Jew”, a character that already appears in his early work. In New York, they had friends, especially in the Jewish community, with whom Chagall could speak Yiddish or Russian, as he never learnt to speak English. Nevertheless the situation in Europe remained a constant source of anguish. In those circumstances, Bella’s death was even more destructive. His daughter Ida, now married, finally found a young French-speaking English woman to be his housekeeper. Virginia Haggard-Mc Neill was 30 and Chagall was 57. She was vivacious, cultured, cosmopolitan, and herself in a precarious situation. After six months they became lovers and she shared his life for seven years, first in up-state New York, then in France. Together they will have a son, David. Her companionship drew Chagall back to his easel. He later said: “Bella sent you to watch over me. Rembrandt had his Hernrikje Stoffels, to comfort him from Saskia’s death, I have you”. However, Bella remained forever his muse and a part of him. She appears in many of his subsequent works, often as a bride.

Horse-woman, a love poem in blue and vermilion

In Paris, Chagall had become great friends with many poets – some of them were well-known surrealists. He himself wrote poetry in Yiddish. But colors were his true medium. From colors he created forms and expressed his feelings and his dreams. In their immediacy they become poetic short cuts.

As André Breton, the leader of the Surrealist movement in France, said: “Chagall brought the metaphor into 20th c. painting”.

Our painting is a metaphor for closure and the beginning of a new life. The red, double-headed, hybrid representation of the couple stands in the center, and is much taller than the side figures. Bella is the central female figure to which the red horse is physically attached. The red horse is Chagall who often represented himself as a donkey, a goat, a rooster or a flying fish. Already in 1911 Chagall had dedicated a picture to Bella, entitled “The beauty and the Beast". The same theme recurs in his work called “Mid-summer nights dream”, where he appears as a goat. Here, their heads are parallel, both bent down. We can feel heaviness and melancholy. No levitation as in many of his other works. They are wedded for life, an eternal part of each other.

However, on the left, a young woman, also in the nude, but a smaller figure, emerges from the all-enveloping blue. In fact, she is herself blue, holding a large bunch of flowers. She may well be Virginia. The flowers, the presence of love and happiness for Chagall, are back in his life. Bella had introduced flowers in Chagall’s life and painting, back in Vitebsk in 1915. “I had only to open my window and blue air, love and flowers entered with her” (Marc Chagall: My Life). The colors of Virginia’s bouquet are rather subdued, compared to earlier representations of flowers. Touches of pink and white lit by the large, white full moon. The green, which encircles the bouquet, could be construed as a sign of renewal. There is also music: the vivid colors of the violin held by a fish glow to the right of the horse’s head. Music played an important role in his early Hassidic life and the fiddler is one of his most famous characters. The fish too is a recurring presence in his work. It refers to his childhood: his father worked in a fishery, his mother sold herring in her small shop, and fish was also an important part of their diet and festivals. It is also considered as a sexual symbol. So, the couple, the female figures and the fiddler fish constitute the three vertical pillars of this painting.

We have already mentioned the dominating color blue, which permeates the rest of the picture. Sidney Alexander remarks in his biography of Chagall “Chagall’s blue is as metaphysical as medieval gold”. Thus he sees Chagall’s work as a continuation of medieval mosaics, early Byzantine painters and icons. It is certainly true that one often talks of Chagall’s blue. It is almost his signature. He himself said” Why blue? Because I am blue like Rembrandt is brown”. (Quote from Baal Teshura, Marc Chagall, Taschen 1998). Note this second allusion to Rembrandt for whom Chagall had the greatest admiration and with whom he identified. Stressing the power of color in Chagall, Picasso said: “When Matisse dies, Chagall will be the only painter who understands what color really is”.

As for the hybrid figures, which recur in many of his works, they have long been part of European profane and religious art, including the works of several of his contemporaries. Chagall shared their desire to abolish the separation between the realms of the creation and it is no surprise that he took great pleasure in illustrating La Fontaine’s fables. His animals do not belong to the wild, but to the world of his youth, in Bielaruss. There is no key to understand how he uses them, no more than there is a key to understand his other recurring symbols. Their respective meaning is dictated by the artist’s vision of the whole scene.

Although the Horse-woman is more static and quieter than many of his larger scenes, it possesses the same intensity and poetic form of expression. It is an intimate picture, saddened by the past, but open to a happier future, and rich in subtle allusions. Here again, painting and story telling are but one. “Complicated clear Chagall with his concealed confessions and sly revelations” (Sydney Alexander, Marc Chagall, a biography).

Notes: In 1947, Chagall paints a self-portrait where the emphasis is on himself: Self-portrait with a wall clock. Here again he has the head of a red horse and a woman’s head comes out of his body, nestled slightly behind his. It could be Virginia. This time, he holds a palette and paintbrushes and stands in front of a picture of the Crucifixion where a bride who is probably none other than Bella comforts Christ. Is he the Crucified? That period of his life was happy. He, Virginia, and David lived in the country surrounded by farm animals and, Chagall could devote himself to his work. However he also carries within him the sadness of a difficult past and the scar of a great loss.

The red horse

Chagall was familiar with Fauvism and German expressionism where colors are independent of the object represented. He was also a friend of the Delaunays who brought color back into cubism and introduced him to the Blue Rider movement. Franz Marc was famous for his red and blue horses.

Biography

The elusive Marc Chagall by Joseph A. Harris Dec 1, 2003 (Smithonian magazine)

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/chagall.html

Chronology

1887 Born in Vitebsk, Russia (present day Belarus)

1906-1910 Studies in St.Petersburg

1910 Moves to Paris. Discovers a new light, the Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, and Les Fauves. Lives in utter poverty at La Ruche (the Beehive), a building inhabited by artists and poets in Montparnasse.

1914 Returns to Russia

1915 Marries Bela Rosenfeld

1916 Birth of Ida, their daughter.

1918 Appointed commissar of the arts in Vitebsk

1920 Moves to Moscow

1922 Moves to Berlin

1923 Returns to Paris

1939 Moves to the South of France

1941 As a Jew, he must flee France. Takes refuge in New York with Bella and Ida.

1944 Bella dies very suddenly in NY state.

1945 Virginia Haggard-Mc Neill is hired to take care of him. They become lovers and move with Virginia’s daughter to High Falls, in the Catskills

1946 Birth of David, their son.

1947 Chagall and his new family returns to France where they settle in Vence.

1951 Virginia leaves Chagall and takes boith children with her.

1952 Marries Valentina Brodsky (Vava)

1985 Dies in St.Paul de Vence, in the south of France. He is 98 and never stopped working.

Easel painting, murals, ceilings, stained glass windows, ceramics and sculpture. He worked in all those domains.

Prepared for the SBMA docent council by Jacqueline Simons,

Bibliography

Virginia Haggard, Seven years of plenty, My life with Chagall

Sidney Alexander, Marc Chagall, a biography

Chagall, connu et inconnu, catalog of the 2003 exhibits at the Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris and at the San Francisco museum of modern Art. Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris, 2003.

Franz Meyer, Marc Chagall. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers, New York

POSTSCRIPT

Chagall and his family were so angry when Virginia Haggard left Chagall that the seven years she shared with him were obliterated from his biography. Only his professional activities during that time are mentioned.

- Franz Meyer, Chagall’s son-in-law

Undated photo of Chagall.