Mary Cassatt

American, 1844-1926 (active France)

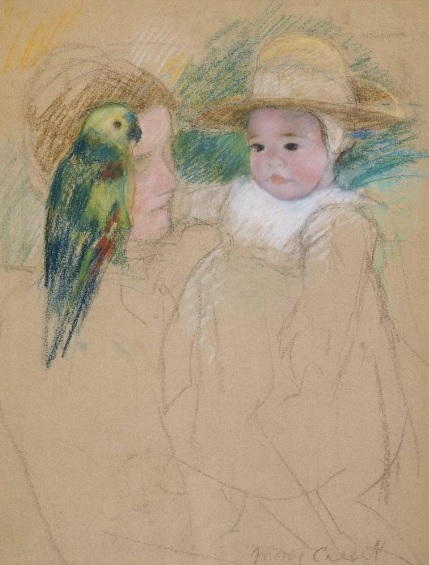

Hélène of Septeuil with Parrot, 1889 ca.

pastel on grey paper

26 x 20 in.

SBMA, Gift of Dwight and Winifred Vedder

2006.54.3

Portrait of Mary Cassatt by Edgar Degas, ca. 1876, detail

"I admired Manet, Courbet and Degas. I hated conventional art." - Mary Cassatt

RESEARCH PAPER

Mary Stevenson Cassatt “The Painter and the Poet of the Nursery” was born on May 22, 1844, in Allegheny City (Pittsburgh), Pennsylvania and died on June 14, 1926, in France at the age of 82. It can be said she single-handedly brought Impressionism to America.

“Helene of Septeuil with Parrot” is incomplete, with the mother’s body and arm barely sketched in. Yet still, Cassatt’s classic “circle” of touch, reminiscent of a Madonna image, is visible with the baby’s arm across her mother’s neck and the mother’s right shoulder and arm reaching down and over the child’s knees. The circle is completed by the child’s left arm. The pair are an intimate unit. They appear to sit in a plane just behind the dark, bright parrot who seems to gaze into this scene of maternity.

While the child’s face is complete, highlighted by her white sailor’s collar, her intense, black button eyes are less clearly directed, but suggest they are looking at the parrot. From the slant of the mother’s head and face, she appears to be looking at her daughter. The details of her face are not complete. The dark green of the parrot is balanced by the background which emphasizes the face, upper body, and hat of Helene. Most of the image is unpainted paper. Cassatt has strategically used white around the child’s button nose and pink lips which keeps the viewer focused on the chubby baby face. She has added some white feathers to the bird, again keeping our eyes on the upper one-third of the image.

Even while incomplete, this is clearly the work of Mary Cassatt. It evokes feelings of calm, warmth, and protection. You can see the individual strokes of pastel in the parrot’s feathers, the mother’s hair, as well as the teal green background. Somehow, although unfinished, you can appreciate the ‘heft’ of this well-fed child as she stands supported on her mother’s lap.

Septeuil is a commune in the Yvelines department in the Ile-de-France region in north-central France. It is in the countryside, outside of Paris.

At age 15 Mary began her studies at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts where 20% of the students were female. Unlike Cassatt, most of these women did not plan a career in art. She struggled under the patronizing comments of male students and teachers and the policies of the institution which did not permit women to work from live models and restricted their assignments to still life and flowers, which caused Cassatt to leave the Academy.

Her mother, a strong proponent of educating women, took the family on a five-year journey through Europe during which Cassatt became fluent in French and German. Mary, her mother, and friends returned to Paris in 1866.

The Ecole des Beaux Artes did not admit women, so Cassatt began private lessons with Jean Leon Jerome, a highly regarded painter, known for hyper realistic techniques. Cassatt augmented her training and meager income by working daily as a copyist at the Louvre, where copies were sold to tourists. Here she became friends with Elizabeth Gardner, an American academic and salon painter, who would marry artist William Bouguereau. While Cassatt was stubborn, a feminist, and pro-suffragette, Cassatt obtained a police report to wear pants in public.

The Franco-Prussian War began in late summer of 1870, and the Cassatt Family returned to America, in Altoona. Mary’s father, still resistant to her plan of becoming a painter, said he “would rather see his daughter dead than live abroad like some Bohemian.” He agreed to pay for her living expenses, but not for her art supplies.

In addition, she was dismayed at the lack of paintings to study. Close to giving up she wrote that she had “torn up her father’s portrait, closed her studio, and had not touched a brush for six weeks.” She traveled to Chicago and ended up losing some early paintings in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

Luckily, her work had attracted the attention of the Archbishop of Pittsburgh who paid for her travel and part of their stay in Parma, Italy. Cassatt attracted positive attention in Parma where she satisfied her obligation to the Archbishop.

Cassatt decided to live in Paris, where her sister Lydia joined her in 1877. The two women were each other’s chaperones with Lydia, often the main model, dying in 1882 at age 45 of chronic kidney disorder. Mary became confined to the home as she was without a chaperone. As a result, there was a marked increase in her painting women and children at home. Her hallmark.

Mary Cassatt tried to work in a traditional manner for ten frustrating years submitting works to the Salon before striking out with the Impressionists. She was openly critical of the politics of the Salon. Her observation that works by female artists were often contemptuously dismissed unless the artist had a friend on the jury, prompted her to say, “she would not flirt with jurors to curry favor.”

In 1877, for the first time, Cassatt had two submissions rejected and was not represented in the Salon exhibition. Just at this low point, Degas invited Cassatt to show her works with the Impressionists, (also known as Independents or Intransigents) who varied greatly in subject matter and technique. Impressionists used quick brushstrokes to capture the image in the moment. The emotions evoked in the viewer did not require details. Cassatt would quip that she used quick brushstrokes to capture the scene before the baby started crying.

Degas had seen Mary Cassatt’s painting “A Cup of Tea” at a prior Salon and exclaimed, “Voila. There is someone who feels as I do.” Similarly, Cassatt, upon seeing pastels by Degas in a shop window, responded, “Seeing his work changed my art, changed my life. I saw art then as I wanted to see it.”

Thus, began a professional and personal friendship which lasted forty years. It is ironic that Degas, a misogynist, and Cassatt, a feminist, often worked side by side, and at times with Degas adding his touch to Cassatt’s canvas. It was Degas who introduced Cassatt to pastels. She later invented a process of creating “a soup of crushed pastel mixed with milk and oils” which she at times applied with a brush.

Degas also introduced Cassatt to copper engraving, of which he was a master. He encouraged her work in prints.

In 1890, the Ecole des Beaux Artes held an exhibit of Japanese woodblocks. After seeing this exhibit, Cassatt made her colors lighter and used delicate pastels in blocks of color within clear contours. Experts said: “These colored prints now stand as her most original contribution, adding a new chapter to the history of graphic arts. Technically as color prints they have never been surpassed.”

In 1890, the Impressionists disbanded after their eighth and final exhibition. Mary Cassatt financially underwrote this exhibit. She maintained contact with some, and continued to promote their work to wealthy American collectors stipulating that these collections be donated to American Art Museums. One example is the Impressionist Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, donated by the Havemeyers, Cassatt’s friends.

Coupled with ill health, increasing blindness, and the loss of family members one by one, Cassatt became a recluse. By then she had produced 200 prints and 2200 paintings. In her advisory role to American Art museums, she was responsible for bringing Impressionism to America.

It was Cassatt’s belief that “a woman should be Someone, not Something.”

And so, she was.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Linda Gorin, 2024.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cassatt, Mary, The Complete Works of Mary Cassatt, 2017-2022.

www.marycassatt.org

Horejs, Jason, A Moment in Art History, Mary Cassatt: Painting the modern woman, The Lost Impressionists, Xanadu Gallery, Scottsdale, AZ.

Weinberg, H. Barbara, “Mary Stevenson Cassatt, 1844-1926, In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.

COMMENTS

Born to a prominent Pennsylvania family, Mary Cassatt spent her artistic career in Europe. Though unmarried, she was no stranger to the family life she so often depicted: her parents and sister moved to Paris in 1877 and her two brothers and their families visited frequently. Today considered an Impressionist, Cassatt exhibited with such artists as Monet, Pissarro, and her close friend Degas, and shared with them an independent spirit, refusing throughout her life to be associated with any art academy or to accept any prizes. She stands alone, however, in her depictions of the activities of women in their worlds: caring for children, reading, crocheting, pouring tea, and enjoying the company of other women.

At fifteen, she was admitted to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and four years later moved to Paris where she studied briefly with Jean-Léon Gérôme, but chiefly educated herself by copying at the Louvre. In 1872, already under the artistic influence of Courbet and Manet, she established a studio in Spain, studied the work of Velázquez and Ribera, and produced a series of paintings of local subjects with strongly modeled features placed against dark backgrounds.

In the Salon of 1874, Edgar Degas saw a painting of Cassatt’s which prompted him to exclaim, “Voila! There is someone who feels as I do.” That same year, Cassatt noticed several Degas pastels in a shop window and wrote, “It changed my life! I saw art then as I wanted to see it.” Soon thereafter they met, beginning a friendship and artistic relationship that would last forty years.

Degas introduced her to other members of the emergent impressionist fraternity, and for nine years, as the only American, she continued to exhibit with them and help organize their shows. She always found their company congenial and stimulating, and as her most recent biographer points out, “for the first time Cassatt found people whose biting, critical, opinionated attitudes matched her own.”

It is noteworthy that both Cassatt and Degas preferred to call themselves “Independents” rather then “Impressionists”; both always insisted on the integrity of form in their painting, whereas Monet, Pissaro, and others tended to dissolve form into light. Like them, she initially employed a high-keyed palette applied in small touches of contrasting colors. However, over time, Cassatt’s style became less painterly, the forms more solidly monumental and placed within clear linear contours.

As a woman in nineteenth-century Paris, she lacked opportunity to depict the diverse subject matter available to her male colleagues: cafés, clubs, bordellos, and even the streets were not comfortably accessible to genteel ladies. The domestic realm, with occasional forays into the theater, became her field of activity. Women and children and family members were generally the subjects of her work, and she became chiefly known for her depictions of mothers and small children. In these “Madonna” paintings she sought to avoid anecdotalism and sentimentality, overcoming the limitations of her subject matter by endowing it with firm structural authority and subtle color interest.

In later years, her eyesight failing, she turned increasingly to pastels, as Degas had done under pressure of the same condition. Like Degas, she became a preeminent exponent of that difficult medium.

In 1872, Cassatt formed a close friendship with a young American in Paris, Louisine Elder, soon to become the wife of H. O. Havemeyer, the reigning “sugar baron” of the American Gilded Age. A woman of discriminating taste and formidable wealth, Louisine turned to her artist friend for guidance in assembling a collection of paintings. In time, they amassed a comprehensive array of impressionist work. Much of the collection was donated to American museums and contributed significantly toward the shaping of public taste and general acceptance of what has since become the most popular of all painting styles.

- Smithsonian American Art Museum

https://americanart.si.edu/artist/mary-cassatt-770