James Casebere

American, 1953-

Sea of Ice, 2014

Pigment print, edition of 5

41 3/8 x 52 3/8 in.

SBMA, Museum purchase with funds provided by the Erik Skipsey Fund

2019.15

James Casebere, undated photo, Minneapolis College of Art and Design

"The novels by Latin American magical realists showed how history is rewritten by each successive military dictatorship. I look at photography the same way: as a fiction, as representative of a particular point of view." - James Casabere

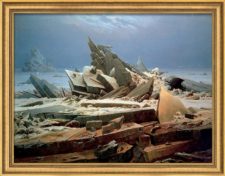

Casper David Friedrich - The Sea of Ice, 1823/24

COMMENTS

There’s a golden yet unspoken rule in architectural training and practice that scale models should be neither too realistic nor too detailed. Thus, trees and human figurines are just tolerable, but curtains, furniture, and other everyday features are questionable, if not prohibited. A model needs to retain a relative degree of abstraction as a material object to accomplish its conjectural quality—that is, to exemplify the project to which it gives scalar form. One of the most intriguing qualities of the architectural model is therefore how it balances materializing abstract plans with telling particular stories. This might explain its appeal to artists in the post-Conceptual era, as it allows for a material negotiation between idea and image, concept and object.

Over the past four decades, American artist James Casebere has built scale models, but only to photograph them. For him they serve as mere devices to make pictures. From the very start of his practice, in the mid-1970s, as he declared in a recent interview, the reproduction had to be the work itself. His interest in architecture derived from its capacity to deliver imagery for photography to capture. Modeling and then photographing the built environment allowed Casebere to address his social context and to trace both its historical and ideological formation. Domestic interiors and American vernacular architecture came first, followed by edifices of power and control, carceral structures, flooded interiors, world heritage sites (mostly Islamic), and lately, suburban environments. Whereas his early models often remained rather rough and schematic, the recent work has become ever more detailed and particular...

An explicit reference to painting was also to be found in Sea of Ice, 2014, a photograph of a meticulous material remodeling of Caspar David Friedrich’s Sea of Ice ("The Failed North Pole Expedition"; "The Wreck of Hope"), 1823/24. Casebere, however, omits the shipwreck, the very element that introduced narrative into an otherwise almost abstract picture.

Casebere radically works against the grain of conventional model-making. A model’s degree of detailing, the artist demonstrates, does not stand in a reversely proportional relationship to its capacity to stir one’s imagination regarding the future reality it projects. Nor is a plainly realistic model anecdotal by default. Casebere achieves generalization through extreme particularization. Today, when polar ice caps are melting at terrifying speed and seashores around the world face rising tides, his photographs remind us that ecological wreckage is not a distant tale, but a real story that is unfolding in our very own twenty-first-century backyards.

- Davidts, Wouter. “James Casebere,” Artforum, May 2014.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Using the camera to create fictional narratives rather than to record the visual facts of the world, James Casabere based this powerfully atmospheric photograph on an 1823/24 painting of the same name by the German Romantic-era artist, Casper David Friedrich (1774-1840). Casabere built and painted a three-dimensional tableau in his studio that reproduced Friedrich's basic composition but heavily reduced the level of detail, and rendered the far horizon darker and even more forbidding. He then photographed this scene and enlarged and framed the resulting image to take on the scale, presence and effect of a traditional landscape painting.

Friedrich's jolting early 19th century vision of the remnants of a destroyed ship, almost wholly submerged amidst towering, jagged plates of pitiless ice, is an allegory of humankind defeated by a far more powerful yet entirely indifferent Nature. In summoning but not exactly replicating Friedrich's bleak yet mesmerizing panorama - there is no ship in the photograph, for instance - Casebere's work raises contemporary questions about the future of such Arctic scenes in the face of climate change, while providing an enthralling visual experience that boldly alloys the traditionally separate art forms of painting and photography.

- Ridley-Tree Gallery, 2019