Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

French, 1827-1875

Genie de la Danse, 1875

terracotta

40 x 18 x 30 in.

SBMA, Museum purchase with Deaccessioning funds from gifts of Joanne and Robert Kendall and Mrs. Courtney Hutton

1988.5

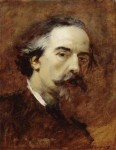

Self portrait of the French painter and sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux.

RESEARCH PAPER

SUBJECT & TECHNIQUE

The Genius of Dance was created by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux in 1869. The artist's smooth, flowing, energetic technique succeeds in making the sculpture a vibrant, almost living and breathing dancer, ecstatic in his abandon and adoration of the art of dancing.

DESCRIPTION

The terra cotta sculpture, 39 inches in height, was cast from a large marble group entitled The Dance in Carpeaux's atelier in Paris in 1872. It is a stunning male figure with arms upflung, a tambourine in the right hand. One of nine compositions in the monumental "Dance" group, a cupid holding aloft a jester's rattle frolics at the base of the statue, which is mounted on a tree stump. The dancer's robe is draped in back, and several females are dancing around him to the beat of his tambourine. The artist did not rework the sculpture at all; instead, it was reduced directly from the original plaster model for the group by a mechanical process. Terra cotta copies were made in three sizes, and in 1873 the artist began selling them commercially. Though bronze copies were made, they were not listed in the studio inventories, so it is likely that they were produced by Carpeaux's atelier after his death.

BIOGRAPHY

Born on May 11, 1827 in Valenciennes, Jean-Batiste Carpeaux was the son of Joseph, a mason, and Adele, a lacemaker. The artist was one of five children, and was educated at the local Ecole des Freres and at the Academie de Peinture et Sculpture. In the 1830's the family moved to Paris and in 1842 Carpeaux was enrolled at Ecole Gratuite Dessin, a school run by the French Government offering workers free instruction in the basic skills o£ drawing, mathematics and modeling. Graduating from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1844, he then became a student of the sculptor Francois Rude. In 1850 Carpeaux left Rude, a politically controversial sculptor, to study with Francisque Duret. In 1854 the young artist won the Prix de Rome with his piece, "Hector Imploring the Gods in Favor of His Son, Astyanax," as Duret had predicted.

Receiving a scholarship to study at the French Academy in Rome, there to create an antique marble sculpture, Carpeaux went to that city in 1856. Inspired by Michelangelo, he strayed from his studies and sculpted the "Ugolino and His Starving Sons," which gave him glory in Paris. This reintroduction to Paris brought many official commissions. He was commissioned to do decorative work at the Louve, and then was selected by the architect Charles Garnier to create a sculpture for the Opera facade. His piece was to be a dance. Although dissatisfied with the subject, he worked for four expensive years to create the controversial Dance, unveiled in 1869. This piece was severely criticized for its nude female dancers. Carpeaux later decided to extract several figures from the group and rework them into small statuettes. These figures became very popular.

Due to financial burdens, he established his atelier in Paris in 1866. His family and political problems prompted Carpeaux to move to England in 1871, where he was successful in exhibiting his works. When he returned to France, he found his atelier in ruins as a result of the Franco-Prussian war. Family problems continued and he was plagued with poor health, including eye problems, in his later life. He died in 1875, of cancer. Just two months before his death, he was made a Knight of the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honor.

Carpeaux was the leading sculptor in the period of French history known as the Second Empire (1851-1870). Not only was he awarded several important state commissions, but he was recognized as the unofficial favorite of Emperor Napoleon III, who virtually completed the building of the Louve.

STYLE

This was the heart of the Romantic period. Although a product of traditional education, Carpeaux played a very important role in a transitional period of art history. His highly expressive style defied many conventions of the time and his work was regarded as energetic realism that was a forerunner of the next generation, especially the art of Auguste Rodin. Though his sculpture was often controversial, he never compromised his search for a style based on any formal criteria.

Many of his pieces bore the title "Genie" (literally "Genius") in French the equivalent of the English "Spirit" or "motivating force." His work resembled the more sophisticated characteristics of a genie -- Bartholdi's "Genius in the Clutches of Miery." "The Dance" is also reminiscent of Duret's "St. Michael Overcoming the Dragon," Raphael's "St. Michael" and Michelangelo's "Risen Christ," which he copied several times in order to understand the upward movement needed in his "Genius" figure. He used the Princess Helene de Racowitza and the workman Sebastian Visat as models.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

J. B. Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Ky., "Nineteenth Century French Sulpture," November 3-December 5, 1971.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, "The Romantics to Rodin," March 4-May 25, 1980.

Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, "A Romance With Realism," Williamstown, Mass., May 6-August 27, 1989.

Wagner, E. Middleton, "Sculpture of the Second Empire," Yale University Press, 1986.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council, by Dorothy C. Jefferson.

POSTSCRIPT

………additional information from the docent files by Carol Spears

This is a terra cotta sculpture by John Baptise Carpeaux – done in 1875 and called GENIUS OF DANCE.

Carpeaux was a French sculptor born in 1827. He died at age 48 - a short but productive life.

Carpeaux was a student of Francios Rude, who taught that structure was everything. Carpeaux deligently practiced Rude's techniques. If you look closely at our two figures you will see how precise and realistic the human forms are. There was a great deal of time spent studying human anatomy and drawing live models.

This technique was in conflict with the way the French Academy viewed art at this time - they believed that nature should be idealized. Dispite this, Carpeaux was the leading- sculptor in French history between 1851 and 1870. He was the unoffical favorite of Napoleon III and received many state commissions.

Carpeaux was also very moved by Michelangelos work and this inspired him to express the inner emotional state of his figures. Looking closely at our figures - you can clearly see that they are enjoying themselves!

Besides being a sculptor, Carpeaux was a business man. In 1860 he opened his own shop. There he reproduced many of his famous public commissions. These were reproduced as statutes in bronze, Marble and mostly terra cotta. These were sold to private collectors. It's important to know - that these reproductions never compromised his personal standards.

Carpeaux was also a highly skilled draftsman, and considered drawing a way of self instruction. He would carefully do multiple drawings of a subject from all angles - he would study these and change them rather than re-work the clay.

In 1865 a new Opera House was being built in Paris. Carpeaux was awarded a commission to do a piece for it. He was over-joyed - this would give him the opportunity to express this favorite theme "The Spontanity of Movement".

He did numerous sketches of dancers - now in the 1830's in Paris a very lively dance became popular - THE CAN CAN! Carpeaux's sculpture captured the gay spontanity of that dance - look how the central figure is dancing with total abandon. As Carpeaux's sketches started to pull together, the central figure which he named The Spirit was a female and there were eight additional adult dancers with her. However as the sculpture progressed the Spirit took on a more masculine form - the finished Spirit is almost androgynous - expressing a physical freedom. The body is very elongated - telling us it contains a great deal of energy.

In 1869 Carpeaux's sculpture was unveiled at the Opera House. It created a public uproar - it was considered indecent and much too realistic. One person wrote -"He made a group of savages dancing the Can Can in front of the door to the Opera House. The police should have intervened". Under all of the public pressure Napoleon agreed to have the piece removed. However at this time the FrancoPrussian war was escalating and the fury over Carpeaux's sculpture faded. It remained in front of the OPERA HOUSE until 1964 when it was.removed to prevent further erosion and a copy was installed in its place.

Now in 1873 Carpeaux found himself with financial problems, so to alleviate his financial situation and to take advantage of the notorious reputation of the Opera piece - Carpeaux created nine separate works from the original and began to market these smaller statuettes. This piece is one of those nine.

Although Carpeaux is not a well known sculptor today - he played an important part in the transitional period of art history – He:

1. was the catalist for the break from the prescribed technique at that time

2. he forged a new direction for expression for future artists such as Rodin

3. he challenged long standing traditions in the Academy

4. his interest in commercializing art led to innovations that made art available to the private collector

Carpeauxs belief was that art should be a celebration of the Human Spirit.

Looking at the faces of these two figures it's very aparent that Carpeaux had the ability to express the inner feeling of his figures.

Also in the SBMA collection is a bronze portrait bust by Carpeaux, Portrait of Gerome, ca. 1871.

COMMENTS

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s Genie de la Danse, sculpted in 1875 was one of the last works this artist created, and caused the kind of petite scandale the French adore when it was unveiled to grace the new Paris Opera House designed by Charles Gernier. The controversy stemmed from the fact that this nearly nude male statue was surrounded by a circle of completely nude women and what one contemporary critic called a "smirking cherub" below. Instead of gracefully draped Terpsichore, the Muse of Dance, Carpeaux chose to represent Dionysus surrounded by the Maenads, as they celebrate a sensual round of merrymaking.. Even the sculpture’s adornments are Dionysian: grapevines, the symbol of his cult, surround the figures.

The Museum’s terra cotta model (done before the full-scale figure was completed) is only of the central figure of Dionysus and the cherub, but this allows us to see more of the details, especially the superb sculpting of the gown, which seems to be almost dancing off the statue. We can imagine the moment right before this pose when Dionysus would have thrown the robe up over his head as he prepares to strike the tambourine and begin the dance. Carpeaux’s choice of subject is not only daring for his time, but also imaginative and provocative. Perhaps he was reflecting the makeup of the ballet company to be housed in this building, since all the dance masters were male and all the dancers were female (many of the later were kept as mistresses by the exclusive and infamous Jockey Club members, who could buy season passes to the Foyer de la danse, or backstage area, in the Opera House to see the young ladies "warm up."

The introduction of the pointe shoe, circa 1820, followed by the harder pointe shoe of 1860, allowed women not to have to depend on male partners, since they could now dance on their toes without support. This, combined with the influence of the Jockey Club and the writing of such influential critics as Theophile Gautier (who did not like male dancers), led to the gradual disappearance of the male dancer from nearly all western stages except Denmark and Russia. In fact, France would not see a male dancer grace the Paris Opera for approximately 60 years – until 1910, when Diaghilev brought his Ballets Russes to Paris and astonished the Parisians by showing them the incredible Vaslav Nijinsky. One of Carpeaux’s contemporaries, Edgar Degas, recognized the power of the Jockey Club in the world of dance. When asked why two of this favorite subjects for his paintings were dancing girls and race horses, he replied, "Because they are treated just the same—they are both owned by the Jockey Club and when they get too old they are both put to pasture." The original of Carpeaux’s sculpture as been moved to the Musee d’Orsay to preserve it, and a duplicate now stands in its place on the Opera facade.

Professor Frank W.D. Ries, Ph.d., Vice chair of Dramatic Art and Director of Dance at UCSB.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

In 1869, Carpeaux revealed The Dance, a figural group commissioned by Charles Garnier for the façade of the Paris Opera. The sensual realism of the nudes caused something of a scandal. Carpeaux capitalized on the work’s notoriety by extracting elements derived from the original allegorical composition to generate a whole host of new subjects, including this variation. These smaller works found a ready market and helped cement his reputation as the most celebrated French sculptor of his generation.

- Ridley-Tree Reopening, 2021