John George Brown

English, 1831-1913 (active USA)

Pull for the Shore, n.d.

oil on canvas

24 x 39 3/4 in.

SBMA, Gifts from the Estate of Mrs. Stanley McCormick, Norman Hirschl and the American Federation of Arts to the Preston Morton Collection by exchange

1971.18

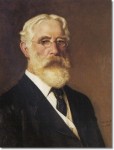

John George Brown - Self Portrait, 1908, 25 x 20”.

“The fact is, that an artist should go direct to Nature and use his own eyes – or his glasses, if he has to wear them. I teach my pupils to see – that is all” (Sheldon, 143).

“Morality in art? Of course there is. A picture can and should teach, can and should exert a moral influence” (Sheldon, 142)

RESEARCH PAPER

Pulling for the Shore depicts seven men and a boy in a rowboat. “Pulling” means to work an oar and six of the men are rowing while the seventh handles the rudder and the boy sits up on the prow looking out to the right. They are on open water, the prow points to a distant coastline on the horizon to the left, and white sails can be glimpsed in the far distance on the horizon line to the right. The SBMA version of Pull for the Shore is a version of a larger work, Pulling for Shore (34.25 x 56.125 in) owned by the Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, dated 1878. The Chrysler Museum painting was exhibited at the National Academy of Design in 1878, and our painting appears to be the smaller undated work included in Brown’s studio sale of 1892. Pulling for the Shore is detailed and has an exactness of finish that comes from the artist’s English training.

The fishermen have fair skin and ruddy complexions; they are rendered naturally and each man’s features are individualized, although somewhat obscured by shadows cast by hat brims. Although we do not know who modeled for this painting, we do know that Brown traveled in 1877 and 1878 to Grand Manan Island off the coast of Maine and that Brown stated his intention to paint the fishing people there: “I desired to paint some Grand Manan fishermen, and I went to Grand Manan and painted them from the life – their fish, their clothes, their boats” (Sheldon, 141). A number of the Grand Manan fishermen oil studies are known and they depict fishermen of similar appearance and dress to those in “Pulling for Shore.” One study in particular, “Grand Manan Fisherman Bringing Home His Oars,” “appears to record the features and distinctive hat of the oarsmen at the front right in the Santa Barbara painting” (Ferber, 156). Brown’s 1913 New York Times obituary gives the title of one of his better known works as: Grand Manan Fishermen Pulling for Shore.

Although these are portraits of specific men, the work is considered a genre painting rather than portraiture. Genre is a French term that refers to types and genre paintings are clearly delineated, often humorous, didactic or moralizing and designed to appeal to a wide clientele (Weinburg xiii). The handsome, athletic rowers in Pull for the Shore

present a robust image of 19th century American character: stalwart men pulling in concert. The theme of adult males in a group appears in several works by the artist at this time (Ferber, 156). Longshoremen’s Noon (1879, Corcoran Gallery of Art) is probably the best known. It depicts a carefully staged scene of immigrant workers on their lunch-break, resting, chatting and smoking. The picture emphasizes relaxation and camaraderie despite the disparate ages and nationalities of the longshoremen. Pulling for Shore bears a resemblance to Winslow Homer’s Breezing Up (1876, National Gallery of Art). It is likely Brown was familiar with Breezing Up. It was exhibited at the National Academy of Design in 1876, Brown and Homer were both at the Tenth Street Studio Building during these years, and Brown’s respect for Homer is documented in Sheldon’s American Painters (1879), where he refers to him as “one of our truest and most accomplished artists” (143).

John George Brown was born in Durham, England, November 11, 1831. At a young age an accident scarred his right hand so severely that the last three fingers were deformed and almost useless. He was apprenticed as a glasscutter at Newark-on-Tyne and completed a seven year apprenticeship in 1845. While employed at the Holyrood Glassworks in Edinburgh, he studied at the Edinburgh Academy under Robert Scott Lauder. Later on in London, he studied briefly at the Royal Academy and supported himself by painting portraits.

Brown is said to have been motivated to immigrate to the United States by hearing the immigration songs of Harry Russell. He boarded a ship for New York in 1853 and on arrival took a position at the Brooklyn Flint Glassworks. In 1855 he married Mary Ann Owens, the daughter of the glassworks manager, and in 1856 with the support of his father-in-law opened a studio in Brooklyn. He enrolled at the National Academy of Design in 1857, studying under Thomas Seit Cummings. Brown began to paint sentimental paintings of street boys, particularly newsboys and bootblacks, with works selling for $5 to $30, and his popularity grew.

In 1860 he moved his studio to Manhattan to the Tenth Street Studio Building at 51 West 10th Street. Brown’s neighbors included George Innes, Frederic Church, John Kensett, Albert Bierstadt, and William Merritt Chase. In 1862 Brown was made an associate member of the National Academy of Design; he gained full membership in 1863. Mary Ann died in 1867 and four years later he married her older sister. In 1889 Brown served as a juror for American Art at the Paris Universal Exhibition, where he was also awarded Honorable Mention. Brown also served on the 1893 national jury for American art at the World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago. From 1899–1903 he was vice president of the National Academy of Design. He died from pneumonia in New York City, on February 8, 1913.

J.G. Brown is best known for his paintings of boys. Brown’s boys were appealing, industrious, cheerful, well fed, and surprisingly clean street urchins. Depictions of the harsh realities of life as a bootblack or newsboy hustling a living on the streets of New York were rejected in favor of sentimental images of Horatio Alger rags-to-riches entrepreneurs, much preferred by successful Americans of the time. His first painting to attract wide attention was, His First Cigar (1860), which sold for $150. During the 1870s and 1880s Brown’s paintings became extremely popular and his images of street children were reproduced so often that he began purchasing the copyrights for his own works. He was known as both a talented artist and successful, shrewd businessman. A lithograph made from one of his paintings was distributed with packages of tea resulting in $25,000 in royalties. In 1882, Harper’s Weekly reported, “…We have no more popular artist in America than J. G. Brown” (DeLay).

Prepared for the SBMA Docent Council by Jill Gallup, June 1977.

Transcribed, researched and edited for content for the web site by Laura DePaoli and Lori Mohr, fall 2012.

Works Cited

Benjamin, S. G. "A Painter of the Streets." A Painter of the Streets V (1882): 267. Web.

Caffin, Charles H. The Story of American Painting; the Evolution of Painting in America. Garden City, NY: Garden City, 1937. Print.

DeLay, Chelsea. "John George Brown | Questroyal." John George Brown | Questroyal. Questroyal Fine Art, LLC, 2012. Web. 24 Oct. 2012.

Ferber, Linda S. "Pulling For The Shore." The Preston Morton Collection of American Art. By Katherine Harper. Mead. Santa Barbara, CA: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1981. 153-57. Print.

Hoppin, Martha J. The World of J. G. Brown. Chesterfield, MA: Chameleon, 2010. Print.

"J.G. Brown, Painter of Street Boys, Dies." The New York Times 9 Feb. 1913: n. pag. New York Times Online Archive. Web. 24 Oct. 2012.

Sheldon, G. W. American Painters. [S.l.]: Ayer Co Pub, 1981. Print.

Weinberg, H. Barbara, and Carrie Rebora. Barratt. American Stories: Paintings of Everyday Life, 1765-1915. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009. Print.

-------------

1 About $600,000 in 2011 dollars.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Pictured here are a group of fishermen, likely modeled on the workers that Brown studied firsthand on Grand Manan Island off the coast of Maine in 1877 and 1878. The composition is a slight variant of a larger version (1878, The Chrysler Museum, Norfolk), which was exhibited at the National Academy of Design, and was likely a response to a painting of a similar subject by Winslow Homer called Breezing Up (1876, National Gallery of Art). Though Brown accrued wealth through the popularity of his more sentimental pictures of the newspaper boys and boot polishers he saw everyday while living in the Tenth Street Studio Building in New York, he clearly had the ambition to create Realist compositions like this one, meant to rival Winslow Homer in their credible portrayal of heroic, American male types. As such, these real-life fishermen were intended to be seen as “manful, daring, and independent as Vikings,” as commented by one critic in 1882.

- Ridley-Tree Reopening, 2021