Brian Bress

American, 1975-

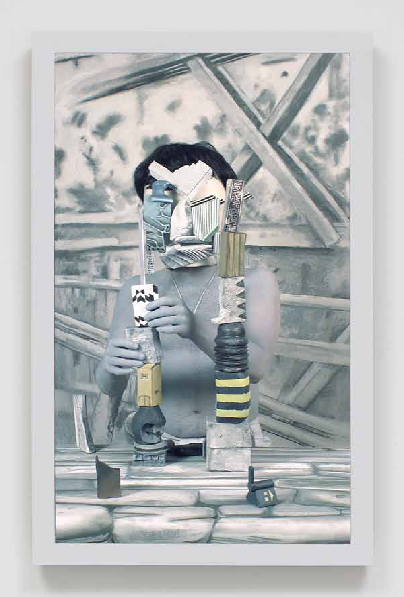

The Architect (Nick), 2012

high definition single-channel video (color), high definition monitor and player, wall mount, framed

22 5/8 x 28 x 4 in. - 43 minutes, 40 seconds

SBMA, General Art Acquisition Fund and Jill and John C. Bishop, Jr.

2012.13a-e

Brian Bress, undated photo

“I enjoy the pushing and pulling between dimensions; that is satisfying to me. I start with an inspirational photograph, then I create a collage, and I make the costumes and sets as the three-dimensional version. After that, we video tape it and place it onto a monitor, back into a two dimensional version.”

-Telephone Interview with Brian Bress, Santa Barbara, January 14, 2014

RESEARCH PAPER

When one approaches “The Architect” video at SBMA, framed and hung on the wall beside traditional paintings, the video appears as if it is a static portrait. It takes a moment to recognize that you are watching a slowly moving video. And as you understand this, you discover that you cannot look away from the screen. The movement of the actor in the video is intentionally slow and mesmerizing, and you find yourself in the TV trance-like state, watching.

“The Architect” video, depicts a masked actor, the artist’s friend Nick, shown from the waist up, wearing a spandex bodysuit painted gray, standing at a table located in a monotone gray set. He is wearing only a necklace and a collaged mask out of which he cannot see. He is caught in the slow moving act of blindly building towers, using very oddly-shaped objects. The mask and the blocks do not necessarily look like anything you have ever seen before, but the subdued color palette, the unexpected complexity of the composition, and the rhythmically slow stacking process is hypnotizing to watch. When the towers eventually fall with seemingly no perceptible reaction from the builder, it is unexpected, and the humor is revealed. While there is a beginning and an end to the 43 minute, 40 second loop that shows the process of the architect stacking objects which eventually fall, the process is continual without strong structure; a viewer can enter and exit the video freely and this adds a gentle nudge of humor that infuses all of Bress’ work.

Everything in the video, the directing, the costume, the set, the mask, the actor’s painted body, and the objects that become towers have been carefully executed by Bress in his studio. His process is thoughtful and his sets, costumes, and random objects are painstakingly hand made by him, selected, and then assembled into the tableau. Of his materials in “The Architect”, Bress says, “you can’t list them, it’s only an image on video. But the materials used to create the piece are paper, foam, pastels, polyfoam, and acrylic paint.” (4, Interview)

In discussing the video Bress says, “ ‘The Architect’ was made for a show at the Armory (Armory Center for the Arts, Pasadena) and was based on a collage that I had made. The collage was inspired by a black and white photo that moved me, and the colors in the piece are based on the collage, where I was trying to capture the feeling of the black and white image. The photo was a compelling image, to me, and a good reason to make the costume. I don’t have a set plan because I find that it stifles the image, or I’ll get distracted from the costume.” (4, Interview)

The title “The Architect” refers to a 40 minute, 43 second continuous looping High Definition single-channel video created for Brian Bress’ first solo exhibition, “Interventions”, created for SBMA and exhibited there July 15 – September 20, 2012. In the Museum-owned video, Bress combines the world of portraiture, illustration, sculpting, painting, video, collage, and objects and his unique view of our understood definitions of these modalities when he integrates them into a video portrait. In creating “The Architect” Bress approached the piece as a painting, taking the two-dimensional world of a painting, and transforming it into a three-dimensional moving collage or a moving painting, and finally into a framed two-dimensional video on the museum wall.

Brian Bress is considered to be one of the most important video artists working and living in Los Angeles today. His videos contain a preoccupation of character and create spaces with objects and color that are at once familiar and alien at the same time. Bress enjoys drawing people into his work using the mesmerizing medium of video, with slow moving, camouflaged actors, layered painterly sets, combined with a subtle sense of humor to explore questions such as, “who am I?”

When Bress was once asked about moving from traditional painting to video as his chosen medium he said, “Everything in my studio was more interesting than the paintings and so I started creating these tableaus that were large enough to get inside of and interact with. And I would arrange them as carefully as I would a painting. I was thinking ‘oh, this is a painting, this is a fixed frame, it’s everything controlled and arranged like a painting’, but I’d never taken it to the next step of trying to force a video to try to occupy the space of a painting.” (7, MOCAtv)

Bress, born in 1975 and raised in Norfolk, Virginia, is a Los Angeles based artist and filmmaker. His parents owned a large pawnshop and Bress spent much of his free time among the detritus of the eclectic objects and interesting characters found there. Spending time among the curiosities, while observing the interesting cross sections of humanity, inspired Bress, who began to develop there his unique concepts about space and his relations to objects that surround him.

From the start, Bress showed an artistic talent for drawing. He graduated with a BFA from Rhode Island School of Design in 1998 where he had studied painting and drawing and began experimenting in video. At UCLA graduate school he merged his broad art knowledge and training, combining his talents of painting and video into something his own and unique. Bress explains, “I always wanted them (various art mediums) to intersect and crossover, but I really couldn’t figure that out. But that was another reason I came to UCLA, because you could work between many different media and no one would care” (9, California Video, p 55). At UCLA interest in video art was growing exponentially. Throughout California, artists explored seriously the medium of video, however their work was characteristically lighter and more humorous than elsewhere. Bress was studying at the epicenter of this explosion and graduated with an MFA in Painting and Drawing from UCLA (9, California Video, p 7-13).

“In making the costume for the Architect, you can’t see out of the mask, and then I came up with the idea that the Architect will construct these ephemeral sculptures. In the end, a friend of mine said, ‘Well that about sums it up’ meaning, that’s life. And I knew immediately what he meant, although I didn’t set out to make that statement, it just happened. There is no building ever built that will never fall over. That’s what’s compelling about it. The blind Architect having no reaction to the objects falling is so Zen” (4, Interview)

Bress says “My goal is to make work that is approachable, and you don’t have to have prior knowledge to understand or enjoy it. I guess I’m a populist and I want my work be approachable to someone who knows about painting or is new to painting.” (4, Interview)

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Wendi Hunter, January 2014

Bibliography

1. Berardini, Andrew. "ArtSlant Interview with Brian Bress". ArtSlant. N.p., Nov. 2010. Web. 15 Jan. 2014.

http://www.artslant.com/ny/articles/show/20025.

2. Campagnola, Sonja. "Brian Bress." Http://www.flashartonline.com/interno.php?pagina=newyork_det&id_art=435&det=ok&title=Brian-Bress, Nov.-Dec. 2009. Web.

3. Chapman, Christopher. "Moving Pictures." Moving Pictures. Portrait.gov.au, Sept. 2008, Web.

http://www.portrait.gov.au/magazine/article.php?articleID=117.

4. "Conversation with Brian Bress." Telephone interview with Wendi Hunter, Santa Barbara, CA, 14 Jan. 2014.

5. Harvey, Doug. "Art in America." Editorial. Brian Bress - Reviews 30 Mar. 2012: Http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/reviews/brian-bress/.

Brant Publishing. Web.

6. "Julie Joyce on Brian Bress." E-mail interview. 24 Dec. 2013.

7. Brown, Lex. "Moca TV Interview with Brian Bress." Http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=awXdw9kqLHA.

MocaTV, 25 Mar. 2013. Web. 15 Jan. 2014.

http://www.youtube.com/user/MOCATV.

8. Philip Martin, Telephone interview. 10 Jan. 2014. Owner, Cherry Martin Gallery.

9. Phillips, Glenn. “California Video: Artists and Histories”, Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Inst., 2008. Print.

10. Santa Barbara Museum of Art. “Interventions: Brian Bress Brochure”. Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2012.

Http://docentssbma.org/bress the-architect-nick/.

11. Winant, Carmen. "Brian Bress - Interventions." Aperture Foundation NY. N.p., 25

Oct. 2012. Web. 15 Jan. 2014.

http://www.aperture.org/blog/interview-brian-bress/.

-Additional Comments

Notes from the Artist, Brian Bress

“The works that I have been making recently, on flat panel monitors inside of colored frames, are much more about the entire object, not just about the image being displayed on the monitor. They are about the thing hanging on the wall, and sensing that there is space behind and around the object.” ( 11, Winant)

In moving toward hanging framed videos Bress explained, “As much as I wanted people to think about painting and talk about painting it wasn’t happening. If I isolated these characters I was creating for these videos and presented them on this fairly new technology of a flat screen monitor, and then hid the monitor inside of a frame, then I could push people a little bit further into thinking about these things as paintings. It seemed really literal and unnecessary in the beginning, but the more I tried the more I made these things to bring people into a dark room to talk about paintings, the more I realized I needed to bring these things into the light and have people encounter them in the spaces that they are used to encountering paintings.” (7, MOCAtv)

While it is obvious that there is an actor in the “The Architect” video stacking the objects, there is no acting, and the human being, together with the camouflage mask against the camouflage set, seems to morph into another being altogether.

Further Bress says, “The Architect’s job was to create stacks, but to do this blind. To give somebody the job of having them stack something blind, it’s hard enough to do that with a vision. So that success of seeing the tower rise, he’s oblivious to it really, and the failure of seeing it fall, it’s all the same to him, and that response or lack of response from the actor is what the lack of vision gave me.” (10, SBMA Brochure)

“In making the costume for the Architect, you can’t see out of the mask , and then I came up with the idea that the Architect will construct these ephemeral sculptures. In the end, a friend of mine said, ‘Well that about sums it up’ meaning, that’s life. And I knew immediately what he meant, although I didn’t set out to make that statement, it just happened. There is no building ever built that will never fall over. That’s what’s compelling about it. The blind Architect having no reaction to the objects falling is so Zen” (4, Interview)

From the start, Bress showed artistic talent for drawing, and at school, he discovered he had a unique social currency and standing with his peers by using it. Between the ages of ten and fifteen, he enjoyed drawing bad political cartoons and taking drawing requests from his classmates. (4, Interview)

One of his favorite childhood places to pass the time was the Chrysler Museum Of Art in Norfolk, Virginia. (4, Interview)

Bress reflected, “I was never bored in class because I could always draw.” (4, Interview)

After high school, he matriculated to the Rhode Island School of Design, where he pursued his love of painting and drawing and began experimenting in video. He graduated with a BFA from RISD in 1998.

After a stint in New York City as a Web Designer, Bress wanted to study under Lari Pittman and Paul McCarthy who were teaching at UCLA. Bress enrolled at UCLA graduate school and while he merged his broad art knowledge and training, combining talents of painting and video into something his unique and his own.

Bress explains, “I always wanted them (various art mediums) to intersect and crossover, but I really couldn’t figure that out. But that was another reason I came to UCLA, because you could work between many different media and no one would care.” (9, California Video, p 55)

Artistic growth was possible for Bress at UCLA where a wide array of media was deployed for student implementation and experimental use. In fact, in Los Angeles, ever since the Sony Corporation pioneered the hand held camera and video tape recorder in 1965, video art has been growing exponentially. Throughout California artists explored seriously the medium of video, however their work was characteristically lighter and more humorous than elsewhere. They were known to use their bodies to explore notions of self, ideas of space, pop-culture, music, cultural taboos, and music. The 1980’s and 1990’s brought further technological advances through better sound, color, graphics, editing capabilities. Meanwhile, Bress was studying at the epicenter of this explosion and graduated with an MFA in Painting and Drawing from UCLA. (9, California Video, p 7-13)

Bress recalled “UCLA had a lot of big name professors who gave it gravitas at the time I was there. I really remember the workshops and classes taught by Charlie Ray, and John Badassari. Hirsch Perlman really impressed me with his teaching abilities.” (4, Interview)

This transition has been described as “he plays with the notions of subject and background, going back and forth from tri-dimensional to bi-dimensional space: from the space of imagination to the space of representation.” (2, Flash Art) This style is described by his representing gallery as a “narrative collage or a pictorial collage.” (8, Martin Interview)

To create the SBMA show, Bress was invited to display five video portraits (one created for the show The Sleeper) and hang flat-screened monitors encased by frames, on various walls throughout the galleries. These videos hung on the walls alongside Claude Monet, Vincent Van Gogh, Odillon Redon and were scattered strategically throughout the Museum, challenging ideas regarding depiction and representation in a traditional art museum setting. Bress loved be able to choose where his work would hang in the Museum and was very inspired and happy by the show and the results of his efforts.

Bress says, “It was also my first opportunity to be in direct dialogue with an art history that, up until that point, I had only alluded to. It’s one thing to be influenced by the impressionists or the futurists, or American Western painting: it’s another thing to be right next to them. It was a pleasure to see how the collection acted upon the work I made, and the other way around. SBMA gave me a lot of freedom to decide where the work went within the galleries.” (11, Winant) Just before 2012 SBMA Bress show, the Museum acquired “The Architect.”

“The Architect” video, depicts an actor shown from the waist up, in a monotone gray set, standing at a table, wearing only a necklace and a collaged mask, caught in the slow moving act of building towers blindly, using oddly-shaped objects. The mask and the blocks do not necessarily look like anything you have ever seen before, but the composed color palette, the unexpected complexity of the composition and the rhythmically slow stacking process, is hypnotizing to watch. When the towers eventually fall with seemingly no perceptible reaction, it is unexpected, and the humor is revealed. Everything in the video, the directing, the costume, the set, the mask, the actor’s painted body, the objects that become towers, have been carefully executed by Bress in his studio. His process is thoughtful and sets, costumes and random objects are painstakingly hand made, chosen and then assembled into the tableau.

“The works that I have been making recently, on flat panel monitors inside of colored frames, are much more about the entire object, not just about the image being displayed on the monitor. They are about the thing hanging on the wall, and sensing that there is space behind and around the object.” ( 11, Winant)

In moving toward hanging framed videos Bress explained, “As much as I wanted people to think about painting and talk about painting it wasn’t happening. If I isolated these characters I was creating for these videos and presented them on this fairly new technology of a flat screen monitor, and then hid the monitor inside of a frame, then I could push people a little bit further into thinking about these things as paintings. It seemed really literal and unnecessary in the beginning, but the more I tried the more I made these things to bring people into a dark room to talk about paintings, the more I realized I needed to bring these things into the light and have people encounter them in the spaces that they are used to encountering paintings.” (7, MOCAtv)

While it is obvious that there is an actor in the “The Architect” video stacking the objects, there is no acting, and the human being, together with the camouflage mask against the camouflage set, seems to morph into another being altogether. And while there is a beginning and an end to the 43 second loop, the architect stacking objects that eventually fall and then he repeats the blind stacking, a viewer can enter and exit the video freely without strong structure around the piece, which adds to the gentle nudge of humor that infuses all of Bress’ work.

Further Bress says, “The Architect’s job was to create stacks, but to do this blind. To give somebody the job of having them stack something blind, it’s hard enough to do that with a vision. So that success of seeing the tower rise, he’s oblivious to it really, and the failure of seeing it fall, it’s all the same to him, and that response or lack of response from the actor is what the lack of vision gave me.” (10, SBMA Brochure)

When Bress was asked why his masks do not have holes to see or to breathe Bress says, “It’s also shorthand for pay no attention to the person…but you can’t help but think about the person behind the mask.” (10, SBMA Brochure)

In discussing which images Bress will choose he says, “What attracts me to the images I take apart and put back together in my work? That’s a difficult question to answer but it’s one I ask myself sometimes. There are quite a few formal prerequisites that an image must meet before I’ll use it. There’s usually (I hope) a synergy between that of an image I am working on and that of the images I’m appropriating. Many times they need to play off of form, color, tone, etc. of the original image.”

“But once they meet the formal requirements they still need to untether themselves enough from their original source. I think I see a need for the images I use to be led around by the image they are collaged on top of and not the other way for me for a couple of reasons. One is that sometimes revealing the source too early can be a letdown to the piece; the final work fails to come even close to how wonderful the original is. The second reason is that I have no earthly idea what the fuck is going on in these images nor have I done any research to figure them out.”(1, Berardini)

POSTSCRIPT

Notes from Julie Joyce, SBMA Curator of Contemporary Arts

The art of camouflage is heavily used in “The Architect” and Julie Joyce explains, “Camouflage is one of the artist’s most significant tools. In the video portraits, it is used to create a Zelig-like impression, dislocating his characters (and perhaps himself), as if they are at once nowhere and anywhere.” (10, SBMA Brochure)

Commenting on “The Architect”, Julie says, “Personally when I think of this piece I also think of the rise of the "starchitect" (Frank Gehry, Renzo Piano, Herzog and Demuron) and how this has affected art-world politics and the museum experience. Because I'm aware of the heated and ongoing critical discourse related to some of these major museum projects, I find “The Architect” to be very funny--the architect is, essentially, blinded in this piece. Compositionally, I find Bress' work gratifying as well due to its relationship to abstraction. The formal properties of his works -- color, form, the use of collage--are quite interesting and wonderful. I'm also fond of its appeal to Surrealism.”(6, Joyce)

Bress’ work has been compared to portrait photographer Cindy Sherman and to Bruce Nauman's video works, and Eleanor Antin, Joan Jonas and New York artist Mary Reed Kelley. His new work in 2014, includes a commission by LACMA titled Idiom (Brian, Raffi, Britt), a triptych that will hang outside LACMA in a courtyard near the Stark Bar.

COMMENTS

The deeply philosophical question, Who am I? may not be the first one that comes to mind upon encountering Brian Bress’s sly and peculiar video works, yet it is the concealed trigger of their witty mannerisms, eerie quirks, and manic visual cues. Such a weighty question might otherwise come off as belabored, but in the artist’s video portraits it is presented in such a subversive a manner that it may not be consciously recognized by the viewer at all. It instead arrives surreptitiously, like part of a guessing game—a subtly posed Who am I? as a challenge to name a person or thing. Whether immediately apparent or not, the question is there, waiting to be answered, yet with a less strident persistence than a similar query that exists in the artist’s mind. For Bress, the question is rather, Where is the separation between what you make and who you are? In his work, the separation or line becomes not just blurred but unequivocally capricious, perhaps even unnavigable depending upon the precise piece and moment.

Bress’s occupation involves a seemingly inexhaustible list of skills, including illustration, painting, collage, casting and sculpting, pattern-making and sewing, photography, video, and more. His task list reads more like that of producer, director, designer, and cameraman, sometimes wrapped into one—and a visit to his studio feels more like a peek backstage. The artist’s preoccupation is the invention of character. His strange and sizable cast alternates between figures that are more like things, ascending from and retreating back into their backdrops, to cartoon- or Muppet-like creatures and archetypal personages.

Slippage is the realm where Bress ably functions. Material, time, and space are unfixed in his videos, as is the viewer’s perception of them. Camouflage is one of the artist’s most significant tools. In the video portraits, it is used to create a Zelig-like impression, dislocating his characters (and perhaps himself), as if they are at once nowhere and anywhere. Works such as The Architect (Nick) (2012) and others divulge Bress’s interest in dazzle camouflage—the unlikely form of camouflage introduced during World War I that cloaked marine vessels in boldly graphic and clashing patterns meant to confuse rather than conceal. Locating his practice somewhere between the cultural domains of Where’s Waldo phenomena, Dada performance, and Tableau Vivant, the venerated commingles eagerly with the banal. It is this and more with which Bress has created works that conjure the uncanny.

Beneath the irony and whimsy of Bress’s work is a demonstrated reverence for historical art and design. This is just one of the reasons his video portraits behave intuitively within the various galleries of the Museum. Another reason has to do with the way these works provoke.

Who am I? It is an impossible question, made even more ridiculous when the figure is obscured by costumes and masks, as they so obsessively are in these works. Asked why the masks don’t have holes for breathing or even seeing, the artist reflects on his thoughts about achieving character—not simply acting like another, but becoming something else entirely. “It’s also,” he explains, a type of “shorthand for pay no attention to the person…but you can’t help but think about the person behind the mask.” In earlier and other works by Bress, the disguised figure in front of the camera is the artist himself, determinedly achieving his desire “to be there but to be not seen.”ii More recently he has been enlisting friends and acquaintances to act as his subjects. It might be difficult to determine what comes first for the artist - his fixation on the surface, or his obsession with who or what is underneath. Whoever or whatever it is, the brilliance of this work is that it keeps us wondering.

Julie Joyce, Curator of Contemporary Art, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, "Interventions: Brian Bress," brochure, 2012