George Braque

French, 1882-1963

Nude with Basket of Fruit, 1924

oil on canvas mounted on wood

Bequest of Wright S. Ludington

1993.1.2

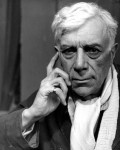

Undated photo of Braque

RESEARCH PAPER

The French painter George Braque is considered to be one of the creators of modern 20th Century art. As a master of the still life, he continued the French classical tradition inherited from the 17th Century realists and Chardin in the 18th Century. His work is characterized by a unique sense of color and sensual form. At the same time, his images reside in a tactile space without distance, in accordance with concepts developed during his formative Cubist years.

Braque was born in Argenteuil, France, and spent his childhood in LeHavre, a member of a middle-class family. His father and grandfather ran successful house painting and decorating businesses, and were considered skilled amateur painters. At age 17 Georges entered the family profession and in 1901 earned his craftsman’s diploma. Many of his artisan’s skills would eventually find creative outlet in his canvases. After a year of military service, he quit his occupation to concentrate on the study of art.

The beginning of the 20th Century was a time of tremendous change. Populations were moving from rural to urban environments. New inventions, such as the automobile, airplane, and cinema, were increasing communications locally and worldwide. Politically, the Balkan powder keg would soon ignite and create a new map of Europe. Artists, reflecting their times, experimented with new ways to see and depict their tumultuous world.

In 1905 The Fauvists debuted their work in the Salon d’Automne, a juried show for alternative art. Primarily artists from northern France and beyond, these artists were inspired by the sun-drenched landscapes of the Mediterranean. Braque eagerly joined their ranks, experimenting with their dazzling, raw colors.

In 1907, a year after Cézanne’s death, two retrospective exhibits of his work were held in Paris. These had a profound effect on Braque, spurring him to experiment with new concepts of form and color. The rhythmic, curvilinear shapes of his Fauvist landscapes gave way to more rigid, geometric forms. He began to eliminate references to sky and horizon, thus flattening the picture plane. His palette softened in favor of the more subdued and refined Cézanne blues, greens, and browns.

About this time, he met Picasso and was riveted by “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” the experimental, groundbreaking painting of five female nude figures. In response, Braque painted a large nude, using the same unnaturalistic approach, the same broken-up planes. (This nude presaged a theme in Braque’s work which would occur rarely and only when prompted by works of Picasso.) Both men had rejected the conventions of realism. Working independently, they had reached the same conclusions and decided to collaborate. They determined that there were differences between images in life and images in paint; so they did not paint objects; they painted the forms of objects, metamorphosing and simplifying shapes to emphasize volume. This was achieved by fragmenting the shapes into geometric facets and then reassembling them, rather like images reflected in shattered glass. Their unique partnership led them to Cubism.

With the outbreak of World War I, Braque became that very expendable instrument of war, a lieutenant in the infantry. The following year he was nearly killed by a shrapnel wound to the head, and his subsequent convalescence was slow and gradual.

By 1919 he had recovered, and his more mature style, incorporating the lessons of Cubism, had begun to appear. Color, form, and the tactile quality of the two-dimensional surface continued to be his foci. He ground and mixed his own colors to achieve the perfect tones and values, excelling in harmonies and textures of color. Although his palette consisted essentially of neutral tones, it was refined, restrained, and elegant. His forms revealed lyrical talents. He loosened the rigid geometry of shapes for a partial return to natural appearances. His shapes were more relaxed, more sensuous, and suppler. He continued to emphasize tactile rather than visual space: that is, he sought to bring the painted image forward to the spectator’s touch, rather than push it away through the illusion of scientific perspective.

During the period 1922-26, Braque was inspired again to paint the female figure. This resulted in a series of nudes based on the classic Greek theme of Kanephori, or ceremonial basket bearers. It is probable that the hefty female nudes of Picasso’s Classic period of 1919 suggested the theme, though not the treatment.

“Nude with a Basket of Fruit” is from this series. The painting, oil on canvas, depicts a basket of fruit borne on the knee of a large, even monumental woman. Earthy in concept, she could represent a pagan divinity associated with fertility and abundance.

The basket of fruit reflects its Cubist roots. The two sides facing the observer are split sharply into light and shadow, without resorting to the convention of chiaroscuro. They are viewed simultaneously with the top, which has been tilted forward to display the simplified shapes of fruit.

The loosely modeled curve of her right arm draws attention, by contrast, to the torso. The rounded volumes of her breasts and supple, heavy folds of her stomach are suggestive of pulpy, ripe fruit. The graceful turn of the head to her left directs the observer to her facial features, which are partially obscured. Perhaps this shadow merely adds an interesting contrast. Or it may represent a spiritual expression of a dual nature. The shading merges with the sensual flow of her darkened hair. It falls over her shoulder and down the sinuous, nearly abstracted form of her left arm to the hand resting on soft patches of drapery. The drape continues across her left thigh, ending beneath the basket. The painting is finally grounded by a luxuriant, mysterious rust red splash at the bottom of the canvas.

The colors – black, white, gray, creamy ochre, olive green, rust red, acid yellow – are surprisingly congenial and elegant. The selection of color is independent of form, exemplified by the creamy ochre tint of the body. The paints are applied upon a ground of rich black that heightens their effect, yet allows the texture of the canvas to emerge. Use of a variety of thick and thin brushstrokes enhances the surface texture and sensations of color and volume.

Braque contrasts space and suggests depth by overlapping the flattened forms, omitting any attempt at conventional treatments of perspective. An unnatural, black outline surrounds the figure, further compressing the distance between the nude and the background. The basket of fruit, her left thigh and left hand are pushed forward toward the viewer, emphasizing their tactile quality.

The fluid lines of the figure and drapery breathe life into the composition, which becomes stabilized by undefined structural forms in the background: On the left an arch curves over the figure: on the right several rigid, linear strips of wall paneling fill the space. Such ambiguities support Braque’s belief that a good picture must have elements that perplex the eye and disturb the mind.

Written by Bonnie B. Sey, April 15, 1993

Prepared for the Web Site by Terri Pagels, February, 2004

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Nude with Basket of Fruit

Brion, Marcel: Braque: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.; New York: 1961.

Cassou, Jean: Encyclopedia Americana, Vol. 4: Grolier Incorporated; Danbury,

CT; 1987.

Cogniat, Raymond: Braque: Crown Publishers, Inc.; New York; 1978.

Cooper, Douglas: Braque: The Great Years; The Art Institute of Chicago;

Chicago, 1972.

Hope, Henry R.: George Braque: The Museum of Modern Art, New York, in

Collaboration with the Cleveland Museum of Art; New York; 1949.

Mullins, Edwin: The Art of George Braque: Henry N. Abrams, Inc.: New York;

1968.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

This monumental seated nude is part of a series that Braque did in the 1920s during the return to classicism that characterized avant-garde art in response to the chaos of the First World War. Eschewing the experimental playfulness of analytic cubism with its multidimensional shattering of forms, Braque returned to the classical subject of the female nude, here replete with a basket of fruit, the conventional attribute of Demeter (Greek goddess of the harvest).

Braque’s muscular, somewhat androgynous nudes of this series appear to be in direct dialogue with Picasso’s equally monumental, classicizing women of the same decade.

- Ridley-Tree Reinstallation, 2022