Adolphe-William Bouguereau

French, 1825-1905

Portrait of Mademoiselle Martha Hoskier, 1869

oil on canvas

18 1/8 × 15 1/8 in.

Gift of Joanne and Andrall Pearson

2011.12

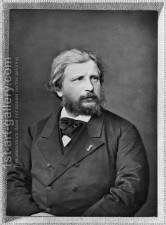

Self-Portrait of the Artist, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, 1879, oil on canvas

“I understood that the subtlety of accents, in contrast with large planes, is what makes drawing great. This truth, which I have yearned all my life to express and which still drives me on, is the secret of art. It applies to composition as well as to drawing proper. It is the principle that must guide both the young beginner and the fully developed artist.” - Adolphe-William Bouguereau

RESEARCH PAPER

The Portrait of Mademoiselle Martha Hoskier was painted in 1869 by Adolphe-William Bouguereau. Mlle. Hoskier was the thirteen year old daughter of the Danish Ambassador to France.

In this formal portrait Bouguereau subtly conveys the self-possession of the child of a diplomat quite accustomed to formal situations.

The eye of the viewer is drawn to the painting not only by the calm gaze of the sitter but also by the dramatic contrast of the delicate paleness of her skin against the dark background. The blue of the ribbons in her hair and on her white dress add color and energize the composition.

While there is the idea of a young woman about Mlle. Hoskier, the subtle shading around her lightly colored mouth and the fullness of her face give the poignant impression of a still young girl who has not entirely left childhood behind.

The gold beads around her flawless neck and the gold earring hanging from her delicate pink ear add warmth to the overall coolness of the painting. Her dark hair almost, but not quite, blends into the darker still background, ringlets hanging just behind her shoulder. Her skin is almost translucent with areas of the blue veins beneath clearly evident. Note too how the line dividing her shoulder from the dark background is not a sharp line but is not defined, giving the skin a softness, if not a glow. Her clear, hazel eyes look directly out of the painting, unblinking.

Bouguereau truly was the master of his materials and technique; a skilled painter and a practiced expert at rendering the illusion of three dimensional form on a two dimensional surface.

Born in La Rochelle, France, in 1825, from an early age Adolphe-William spent his time illuminating his schoolbooks and notebooks with drawings. In the early 1840s his Uncle Eugene arranged for him to take drawing lessons from a professor who had been a pupil of Jean-August-Dominique Ingres and was himself a committed classicist. Again with the help of his uncle, in 1846 Bouguereau moved to Paris to attend the Ecole des Artes, the school of the French Academy, and eventually became a member of the Academy becoming a highly sought after academic portraitist and decorative painter.

As was the Academy at this time, Bouguereau was a traditionalist and conservative in his views as to what constituted fine art, more specifically, fine French Art. He believed in and practiced a method of painting that had been developed and refined over the centuries in order to vividly bring to life imagined scenes from history, literature, and fantasy. Bouguereau deeply believed drawing was the necessary foundation and the beginning of all visual expression. He drew constantly and was known to draw during meetings at the Academy Julien, where he taught, or in the evenings after supper.

Mark Walker, one of Bouguereau's more enthusiastic biographers, has averred that some of Bouguereau's drawings were rendered with the aid of an optical device known as the chambre claire, or camera lucida. This instrument, by means of prisms, allowed the tracing of a subject's outlines, as observed by the artist, directly onto a drawing board. Something akin to a prism on a stick the chambre claire/camera lucida permitted the artist to readily and quickly plot and reproduce certain details which could later be used in the studio as details in a painting, with the final finished rendering dependent on the observation of the naked eye and the skill of the painter.

While Bouguereau did not paint from photographs, he had a large collection of photography which he used to analyze the effects of light on objects. If a figure was to be clothed he would also make drapery studies by posing a mannequin in place of the model and experimenting with the folds of cloth until a position was found that enhanced the underlying forms.

In the Portrait of Mlle. Hoskier the results of this dedication to such studies can be seen in the rendering of her white satin dress and blue bows. Bouguereau frequently used the combination of white and virginal blue when painting portraits of well-to-do girls and young women. Colors that he did not use in his genre paintings of female subjects of the same ages.

Alongside his mastery of line Bouguereau used tone relationships with great authority. He felt that harmony of dark and light tones to be of first importance in painting, as can be seen in the Portrait of Mademoiselle Martha Hoskier.

In Bouguereau's paintings color and light are in service to form as opposed an Impressionist painting where color and light were primary, with form not always of equal importance.

While he was a very traditional and conservative painter he was not a reactionary. He felt women should be welcomed into the Academy and the Academy's Salon Exhibitions, and taught several women as students at the Academy Julien.

Bouguereau was an admirer of traditional art and had no time for anything resembling innovation or the avant-garde and he regarded the ugly and ordinary as unworthy of representation. Yet, he did not attack the Impressionists as did many members of the Academy. His harshest words that I could find were to the effect that because he did not see as they did he could not consider himself to be a viable critic.

The portrait of Martha Hoskier was commissioned at the same time as was a portrait of her mother. Having one's portrait painted by the leading painters of the day was a tradition among the wealthy of Paris in the nineteenth century and such, these portraits are, for us, documentation of a time and life now passed.

Bouguereau's genre paintings, while technically masterful, do not stand the test of time and changing tastes. Today we respond more readily to his portraits. In the genre paintings sentiment replaces narrative. In his rendering of the theme popular at the time, the peasants were clean, comely, posed no threat to the social order, and were fare removed from the reality of the difficult lives of the French rural poor.

The portrait of Madam Hoskier remains in a private collection in Switzerland. The Portrait of Mlle. Hoskier was loaned for exhibition at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Florida from 2009 to 2011. It was then purchased and donated to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in 2011 by Joanne and Andrall Pearson. Prior to 2009 it is believed the portrait was in a private collection in England.

Martha Hoskier Married Maurice, Marquis d'Elbee, in 1879 at the age of 23, they had 10 children. Of these, 4 sons perished in World War I. Of her ten children only two had children, giving Martha 10 grandchildren, then 13 great grand children, 20 great, great grandchildren, 8 great, great, great, grandchildren, and finally 1 great, great, great, great, grandchild born in 2003. By now, I imagine there may be more.

Prepared for the SBMA Docent Council by Francis Hallinan, April, 2012.

Bibliography

Bartoli, Damien with Frederick C. Ross and Mark Steven Walker. Bouguereau, His Life and Works. Antique Collectors Club, Woodbridge, 2013

Walker, Mark. Bouguereau at Work. Art Renewal Center. Web, n.d.

http://www.artrenewal.org/articles/Technical_Articles/WALKER-BOUGUEREAU/WALKER-BOUGUEREAUpage1.php

Wissman, Fronia E. Bouguereau. Pomegranate Communications. San Francisco, 1996

Undated photo of Bouguereau.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

This generous gift from SBMA trustee, Joanne Pearson, fills a gap in the permanent collection, enabling the Museum to provide the academic foil by which the avant-garde’s radical rejection of tradition can be measured. French painter William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825 – 1905) was one of the most successful artists of his generation. Usually categorized as “academic” because of his classical training and highly polished technique, he was cast in less than flattering terms by the Impressionists and their friends; hence, his relative obscurity today. Nevertheless, Bouguereau was avidly collected throughout Europe and America during his lifetime. This portrait, which was painted during the artist’s early maturity, showcases his prodigious technical abilities.

The sitter has been identified as the thirteen-year-old daughter of the Danish vice-consul in Paris, Emile Hoskier (1830 – 1915). Although Bouguereau aspired to be known for his history paintings, his natural gift for portraiture provided him with a convenient means of supporting himself. Bouguereau’s approach is indebted to the art of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780 – 1867), which he would have known through his first teacher Louis Sage, a pupil of Ingres. His teacher in Paris, François-Edouard Picot (1786 – 1868) was a student of Jacques Louis-David (1748 – 1825), providing yet a second link to the neoclassical school. Picot and his friend, Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824 – 1904), the other great 19th-century exponent of French classicism, inherited Ingres’ deep admiration of the Renaissance masters, which they combined with an exacting verisimilitude derived from countless studies done from life.

Bouguereau’s portraits share this suave synthesis of the idealized types drawn from the art of the past and an unerring eye for nearly photo-realistic detail. In this portrait, he captures his sitter’s youthful radiance, presenting us with a beguilingly seductive array of closely observed particulars, from the satin sheen of her blue ribbons to the soft glow of her gold beads.

Ridley-Tree Reinstallation, 2011, Eik Kahng, Chief Curator