Pierre Bonnard

French, 1867-1947

Nude Against the Light, 1909

oil on canvas

Michael Armand Hammer and the Armand Hammer Foundation

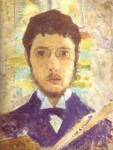

Pierre Bonnard, Self Portrait, Tempera on canvas, 1889

"What I am after is the first impression – I want to show all one sees on first entering the room – what my eye takes in at first glance." - Pierre Bonnard

“A nude by Bonnard is not an odalisque or a nymph or a goddess or a model but a woman observed in the bedroom or the bathroom, almost always self-absorbed, doing something to her body or looking at her reflection or brooding.” -David Sylvester, 1966

RESEARCH PAPER

As if we have just walked in on this woman’s private moment after her bath, Bonnard’s, “Nude Against the Light”, completed in 1909, leaves us feeling almost compelled to look away for fear of startling her. It is evident to us, as the viewer, that Bonnard’s relationship with this woman is more than just artist to model and our impression would be correct as this is Marthe de Méligny, a woman who was Bonnard’s model and muse and who would ultimately go on to become his wife. Here Bonnard paints with his signature style presenting Marthe in her own domestic surroundings, not looking out of the picture but instead, with eyes closed as if in her own quiet moment of time (Whitfield, 1998, pg. 17). A master of depicting domestic interiors, Bonnard’s loose brushstrokes and intentional placement of opposite colors of pink and green in the folding screen, provides a softness to the background of the composition that serves to compliment but not compete with Marthe’s form. Bonnard continues with this deliberate technique in the way he blends the color tones in Marthe’s skin, thereby softening her form, as well. She becomes the focus of the painting yet, at the same time, appears to be an integral part of the room itself.

Pierre Eugène Frédéric Bonnard was born in Fontenay-aux-Roses, a suburb of Paris in 1867. His father was a civil servant at the French War Ministry and following Bonnard’s baccalauréat in 1885, he insisted that his son study law. Bonnard complied with his father’s request; however, at the same time he also applied and was accepted into the Académie Julian. It is there that he met and became friends with a circle of young artists including Paul Sérusier, Maurice Denis and Edouard Vuillard, who, together with Bonnard, went on to form the Nabis. In Hebrew, Nabi is the term for prophet and for this group of artists, Paul Gauguin was seen as their hero.

The Nabis were followers of Gauguin and became known for their use of “flat surface(s) covered with colours arranged in a certain order” (Lynton, 1989, pg. 201). This “radical simplification of form and colour” provided the intensification of their works that was so appealing to them (Lucie-Smith, 2009, pg. 26). This philosophy is especially apparent in the sunlit, interior domestic scenes that Bonnard became so known for. “Nude Against the Light” is one such example of this. Painting with oil on canvas, Bonnard is able to capture the light entering the room from the left while still preserving some degree of haziness in the patterns that surround this young woman. The details of Marthe’s face are not as important to us, the viewer, as is the feeling of intimacy that is evoked when we take in the painting as a whole. One is reminded of Japanese woodcuts in the diagonal line that cuts through the space, the cropping of the figure that is slightly off-center, and the presence of what appears to be a decorative screen in the background. It is not surprising that among the Nabis themselves they designated Bonnard ‘the very Japanese Nabi’ (Lynton, 1989, pg. 201).

Bonnard was also greatly influenced with the advent of photography, especially with the ease of use that George Eastman’s Kodak camera provided (Easton, 2011, pg. 61). Unlike the Impressionists who were known to paint en plein air, Bonnard painted primarily from memory. Norbert Lynton describes his technique as, “he would tack a length of canvas on the wall of a room…and paint two or three quite different subjects on it, working from memory, away from the motif” (1989, pg. 202). Bonnard’s photographs helped him in this manner, as he would use them as a source of reference to aid his memory. In other words, photography became a way to “sketch” the motifs of future paintings (Easton, 2011, pg. 62). Bonnard commented himself on the fact that he was “…very weak, and it is difficult for me to control myself in front of the object.” (Lynton, 1989, pg. 202).

It is during Bonnard’s early involvement with the Nabi’s that Maria Boursin entered his life. By the time of their meeting on a Paris street in 1893, she had already changed her name to Marthe de Méligny, a fact that Bonnard would not discover until many years later (Whitfield, 1998, pg.15). Marthe’s presence, however, starts to be seen in his work almost immediately after this meeting and she went on to become his lifelong companion. “Nude Against the Light” is one of approximately 384 paintings in which Bonnard uses Marthe as his subject model. Like the other Nabis, Bonnard’s works allow for “no real separation” between his work and his private life (Easton, 2011, pg. 62). Although Bonnard and Marthe had already lived together for almost 30 years, the two were finally married in 1925.

Marthe’s health was fragile for most of her adult life and there is little documentation as to what her exact diagnosis was. However, it is widely known that she was obsessive about hygiene and bathing. Bonnard’s compositions of Marthe in and around the bath are some of the most recognizable in Bonnard’s oeuvre. With the outbreak of war in 1939 and Marthe’s failing health, Bonnard found himself confined to the property that he had purchased at Le Cannet, a property he named ‘Le Bosquet’. Even Bonnard’s close friends “adopted the painter’s discretion and reserve in matters concerning her” (Whitfield, 1998, pg. 27). It is possibly that under this umbrella of protection Bonnard chose to forever depict Marthe in what David Sylvester describes as, “constantly the same woman in a rather special sense: as she got older, he went on painting her almost exactly as he had when she was younger” (1997, pg. 138). Marthe died in 1942 and, although Bonnard continued to paint, he felt his loss greatly, and he followed her in death in 1947.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by

Erika Budig, February 2016.

Bibliography

Easton, Elizabeth W. “Snapshot: Painters and Photography, Bonnard to Vuillard”. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011. Print.

Groom, Gloria. “Beyond the Easel: Decorative Painting by Bonnard, Vuillard, Denis, and Roussel, 1890-1930”. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001. Print.

Lucie-Smith, Edward. “Lives of the Great Modern Artists”. London: Thames and Hudson, 2009. Print.

Lynton, Norbert. “The Story of Modern Art”. New York: Phaidon Press Limited, 1989. Print.

Sylvester, David. “About Modern Art: Critical Essays 1948-1997”. New York: Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1997. Print.

Whitfield, Sarah. “Bonnard”. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1998. Print.

Pierre Bonnard. C 1889. Photo by Annette Vaillant

COMMENTS

Strongest as a colorist, weakest as a draftsman, Bonnard was often at his best when a canvas of firmly marked shape helped him structure his composition. In this picture the rectangual shapes at the top and left side assist in giving firmness, as do the value contrasts caused by the backlighting of the figure. For the rest, Bonnard is free to indulge the lavish richness of his purples, golds, and dark greens.

- Armand Hammer Collection Exhibitions, Oklahoma City, 1971

Mirrors, and the use of mirrors to create odd juxtapositions, spatial ambiguity and the sense of forever expanding space—a space of infinite possibilities for seeing—becomes an important element in Bonnard’s work after 1900. His earlier Nabi interiors, like those of Vuillard, close in upon themselves. Now, in the first decade of the twentieth century, most often through the vehicle of the nude in the interior, Bonnard’s involvement with the act of perception and with perceptual psychology leads him to embrace the device of the mirror.

In 1908, Bonnard moved away from his earlier intimate style toward a more impressionistic and atmospheric feeling for light and nature. At this time he also began to explore further the subject of the female nude, which was to remain a central motif throughout his late work. Bonnard’s nudes at their toilette reflect the evolution of a highly personal vision, replete with references to the artist’s own art, his external experiences, and the long and complex artistic tradition in which they are located. The model is most often Marthe—Marthe at her bath, Marthe caught unaware before her dressing table, Marthe partially glimpsed through a mirror. Yet, while the paintings refer to a specific woman, they are about Bonnard’s way of seeing, and, finally, they are also about light—the light that irradiates, denoting possession, and the light that disintegrates, signifying loss.

- Sasha M. Mewman, Bonnard: The Late Paintings, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1984

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

In the first decade of the 1900s, the theme of woman at her bath or toilette assumed primary importance in Bonnard's work. Here he uses his companion, Marthe, as the subject as she goes about her daily ritual of the bath. He has muted any erotic undertones in favor of evoking an atmosphere of warmth and intimacy. The figure is cropped just below her knees, a technique that Bonnard borrowed from photography. By this point in his career, he had abandoned the darker colors of his earlier work in favor of shimmering light and opalescent color. Indeed, the coloristic brilliance of Impressionism continued to inform Bonnard's work well into the twentieth century.

- Ridley-Tree Gallery 2016