Christian Boltanski

French, 1944-

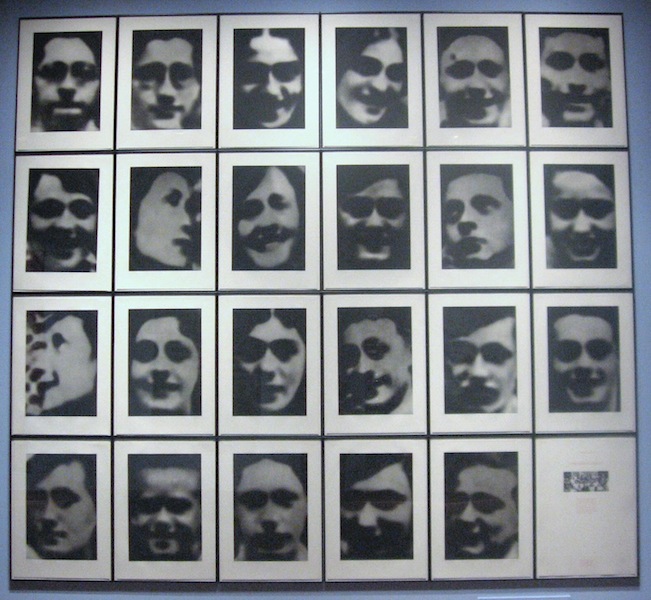

Gymnasium Chases, 1991

portfolio of 24 photogravures

SBMA, Gift of Morris B. Squire and Nurith and Ichak Adizes

1997.76a-w

Undated photo of Boltanski

The following direct quotes from an interview with Boltanski help us to understand him and his art:

“I began to work as an artist when I began to be an adult, when I understood that my childhood was finished, and was dead. I think we all have somebodywho is dead inside of us. A dead child. I remember the Little Christian that is dead inside me.”

“What drives me as an artist is that I think everyone is unique, yet everyone disappears so quickly….We hate to see the dead, yet we love them, we appreciate them. Human. That’s all we can say. Everyone is unique and important.”

“Being an artist does not make me happy…… This is a lonely life…. And what is very lonely is that nobody else can say anything useful to you about your work…..Sometimes we need to forget. For this reason, I do nothing, and I only wait to die. We must be friendly with dying. To be alive is to be honest.”6

RESEARCH PAPER

Artist’s Statement:

“They are all gathered for the last time. It is the end of the (school) year. They are students at the Gymnasium Chases, the Jewish High School in Vienna.

The year is 1931. What has become of them after so many years? What sort of life have they had? One of them recognized himself in this picture.

He escaped the horror and today lives in New York. Of the others I know nothing.” Christian Boltanski

The Artist

Christian Boltanski was born in Paris in 1944, just after the liberation of France from the Nazis. His middle name, Liberté, commemorates that historic event. The circumstances of his birth had a significant impact on his art. Boltanski’s father was Jewish and his mother Catholic. During the German occupation his parents were officially divorced, but his mother hid her husband in a secret room of their home. His mother only officially claimed Christian as her own after she and her husband were remarried. This experience never left the artist.1 His personal history and the events of the Holocaust when six million Jews in Europe were imprisoned and exterminated during World War II are the context of his art.

Of his childhood experience, Boltanski says, “I had a lot of difficulties with my childhood for different reasons, so I invented one, or rather, so many that I no longer have any childhood. I have erased it by inventing so many false memories. An artist plays with life and no longer lives it.”2 Many of Boltanski’s works are filtered memories of his childhood, the hiding and the two worlds in which he was forced to live are evoked in multiple layers of reality.3 He takes an autobiographical approach in his work, both factual and reinvented.

Boltanski is a French conceptual artist who does not use traditional mediums and conventional forms in his art. He challenges assumptions of what constitutes an artwork, using media as diverse as newspaper clippings, used clothing, amateur snapshots and flickering shadows.4 In keeping with the spirit of the artists he admires, Joseph Beuys, Yves Klein, and Andy Warhol, Boltanski believes the function of art is not to transmit information, but rather to ask questions, postulate problems. He was also influenced by the performance activities of Marcel Duchamp, the international Fluxus group and the Italian Arte Povera artists.

The Art

Gymnasium Chases, 1991, is a portfolio of 24 photogravures, based on a photograph of the 1931 graduating class of the Gymnasium Chases, a Jewish High School in Vienna. Although Boltanski has employed many of these photographs in altar-like installations, this is the first time the class is presented in its entirety. He has arranged the black and white photographs neatly in rows. The photographs depict the faces of the students which he has re-photographed and enlarged several times and cropped to reveal close-ups of their faces. In the photogravure process, the prints have become blurred so that they take on a grainy, cadaverous cast.7 The images in these photographs are so enlarged they have lost almost all detail; the heads look like skulls. Eyes are large sockets, smiles have turned to grimaces, and individuality is erased.8 Boltanski’s focus on the individual within a larger group makes this work particularly arresting and poignant.

“For this work, Boltanski started with a small snapshot and then isolated the 23 faces in it by enlarging each one into a single portrait. Through a manipulative process the joyous countenances of youth and promise are transformed into haunting images of overbearing sadness. Because of a masterful exploitation of tonal variations, the hazy black-and-white images peer out at us in anguish. We ask: What has become of these children? Is this what the war brought to innocent faces? What sufferings were they forced to endure? Who among them survives? Why are they thus memorialized? Boltanski chose as his primary themes the loss of childhood innocence, the role of memory in adult life, and the tragedy of mass death.” 9

“Christian Boltanski wishes you, the viewer, to forget that you are in a museum looking at art. He hopes that you will become so rapt in your emotional response to this art that you will leave behind your self-conscious, art-viewing thoughts and typical museum behavior. Then you will be receptive to the power of his art and open to be genuinely touched by the heart-wrenching reactions that his works inspire. In these moments-when your are not thinking about why this is art, how this is art, and what it means, when you are just genuinely reacting-the gap between an “art experience” and a “real life experience” is bridged. This is the power of Christian Boltanski’s poignant and life-affirming art.” 10

For Boltanski, patterns, repetition, repeated images, repeated formats and the ritual like repetitions of his art-making procedures—whether learned from other conceptualists or in the mimicry of everyday life, are the structural basis for almost all of his work. Boltanski used clusters of photographs in the related series of his photo-based installations from 1985 to 1991, variously titled: Omores, Monuments, Archives, the Lycee Chases Altars, Gymnasium Chases and the Bougies. These works collectively came to be known as Lessons in Darkness. “These installations are redolent of death, tinged with a religiosity and also a dose of film noir.”11

Not only are Boltanski’s photographs blurred, but there is a blurred distinction between fact and fiction, illusion and reality in his work. “In struggling to decipher these blurry faces, a viewer can hardly avoid constructing a provisional narrative, a sense of who the anonymous faces represent and what their fate has been. Without specifics to go on, this process becomes fundamentally a matter of self-examination—meditations on the facts of living and dying that are mysteriously and inevitably present in every snapshot.” 12

Boltanski’s work is suffused with a sense of history—political, cultural and personal. On one level Boltanski functions like an archeologist digging in the past, yet the means he uses to reconstruct history are those of fiction, composed from a huge inventory of faces gathered by the artist over a period of years. The images may or may not portray actual victims. Boltanski discounts authenticity which enables him to deal with the vagaries of memory, or with memories he never had—of events that preceded his own birth—simply by fabricating or reinventing them.13 He relies on the photograph’s deception to function as an authentic trace of historical events. Some read these works as homages to the lost generation of nameless children whowere victims of the Nazis. 14

Boltanski uses contradiction and ambivalence in his work to negotiate an “ill-defined” space between memory, history and the esthetic.15 His ambiguous and ambivalent method can be a lament and an icy warning of nihilism or a morbid celebration of the idea of death. Boltanski says that he reconstitutes the past, creating pseudo-autobiographical fiction with little connection to his own experience. He insists that these reconstituted memories were not based on his personal past. These reconstitutions are interesting because of the contradiction they present between photographic and other visual evidence. The photo-based pieces challenge the medium’s built-in claims to truth, while simultaneously exploiting its documentary function.16 Boltanski speaks of presenting a “universal history” of memories and explains his emphasis as a desire for universality.17

Boltanski manipulates a viewer’s experience and emotions, and he makes us aware of the manipulation. The contradictions in his work are obvious, but what makes the work affect us? He relies on basic truths about the power of association and memory.18 The sorrow one feels when first encountering one of Boltanski’s installations gives way to qualms about its sincerity—and then quite possibly to something else.19

Though he is an avowed non-believer, Boltanski has described himself as a maker of religious art.20 “The mock religiosity and mock formalism of some of his work presumably exemplify Boltanski’s ambivalent attempt to produce a contemporary sacred art.”21 He returns again and again to the themes of lost childhood innocence, the role of memory in adult life, and the tragedy of death. In this sense, his work has an aura of spirituality and is a public memorial,commemorating all who have ever died too young. Since photographs record the past, they can also be requiems for the adult’s lost childhood.

Boltanski repeatedly returns to his three themes as if he resists closure. His radical ambivalences are unresolved. At times he seems to turn history into myth. Boltanski triggers emotions associated with collective memories and probes the essential core of human experience. His photogravure process like death transforms human subjects into objects that, like cadavers, more or less resemble one another.22 The images create an awareness of the absent and forgotten. “His photo-installations become moving despite their artifice because….they provoke a coming to terms with issues like childhood loss, innocence and dying. This is the drama of Boltanski’s strange theater. His art unfolds like a play in three acts: grief, doubt and revelation.”23

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Dwight Coffin, 2006

Endnotes

1. Feinberg, p. 1.

2. Marner, p.172

3. Grachos, p.1

4. Feinberg, p. 1

5. Grachos, p. 1

6. Boltanski, p.5

7. Kimmelman, p.34

8. Feinberg, p. 1

9. Feinberg, p.2

10. Feinberg, p.2

11. Kimmelman, p.34

12. Kimmelman, p.35

13. Gumpert, p. 48

14. Gumpert, p. 49

15. Marmer, p.169

16. Marmer, p. 176

17. Marmer, p. 176

18. Kimmelman, p.35

19. Kimmelman, p.35

20. Marmer, p.233

21. Marmer, p.233

22. Gumpert, p.50

23. Kimmelman, p.35

Bibliography: Christian Boltanski

Boltanski, Christian, “Studio Visit: Christian Boltanski, Tate Magazine, Issue 2, London.www.tate.org.uk/magazine/issue 2/boltanski.htm-23k, February 20, 2006

Feinberg, Jean E., Looking at the Art of Christian Boltanski,Cincinnati Art Museum, October 22, 1994 – January 16, 1995

Grachos, Louis, Christian Boltanski, Contemporary Currents, Queens Museum of Art,

19 September – 2 November, 1991

Gumpert, Lynn, Christian Boltanski, Phaidon Press, September 26, 1997

Jacob, Mary Jane and Gumpert, Lynn, Lessons of Darkness: Christian Boltanski, Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art, 1988

Kimmelman, Michael, “Dead Reckoning:From Obituary to Art,” The New York Times, p.35, January 13, 1991

Marmer, Nancy, “Boltanski: The Uses of Contradiction,” Art in America, October, 1989,pp 169-180, 233 & 235

The many faces of Boltanski

COMMENTS

Note: The title and inscription of this work, Gymnasium Chases is the choice of the artist, and not correct English, Austrian or French language. According to Jill Finsten and Walter Kohn the proper would be Gymnasium Chajes. Boltanski has other works of art from this series and they have the same alternative spelling as the one in the SBMA collection. This portfolio of 24 photogravures, is an edition of 15, printed in San Francisco at Crown Point press, 1991. All editions have Boltanski's chosen title Gymnasium Chases, printed on them.