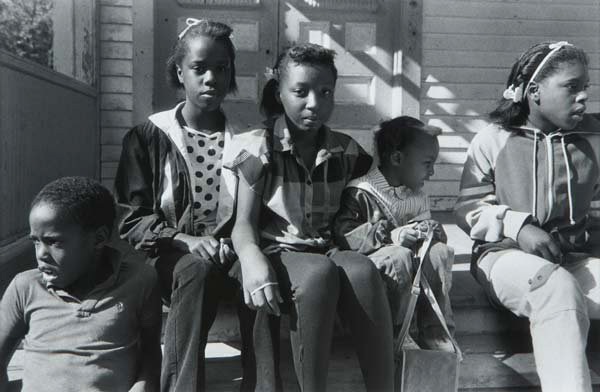

Dawoud Bey

American, 1953-

Five Children, Syracuse, NY, 1985, printed 1996

gelatin silver print

7 7/8 x 12 in.

SBMA, Gift of Arthur B. Steinman

2000.50.18

“When you are able to stand before a photograph of a person who you don’t know, and you still have a connectiveness through that photo — that’s what I try to do.” - Dawoud Bey

COMMENTS

Though Dawoud Bey, the long-beloved titan of African-American photographic portraiture, began his career 40 years ago, his often-repeated origin is worth repeating here: In 1969, Bey, then a young man from Queens, New York, heard about a controversial exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and went to check out the protests. The show, “Harlem on My Mind,” was accused of white voyeurism, anti-Semitism; a survey of Harlem culture, it was notably light on black artists. But there were large portraits by Harlem Renaissance photographer James Van DerZee, and Bey was transfixed — perhaps more importantly, he studied others studying the portraits.

Around the same time, he came across a copy of “The Sweet Flypaper of Life,” a collaboration between photographer Roy DeCarava and poet Langston Hughes, about moments between moments — a woman nuzzling a dog, a subway car mostly empty of riders. Inspiration clicked.

Bey had his subject.

For his first solo show, the now benchmark “Harlem USA,” at Harlem’s Studio Museum in 1979, his photos showed residents of that neighborhood simply being. He conveyed the inner lives of teenagers at a ticket booth, a barber posing with his chair. His portraits often showed nothing but one’s everydayness — a quality often still hard to find among the paintings and photos of people of color in large cultural institutions.

“My work, then, now, is about revealing the human community to itself,” he said the other day, outside his office at Columbia College, where he has taught photography for 19 years. “When you are able to stand before a photograph of a person who you don’t know, and you still have a connectiveness through that photo — that’s what I try to do.”

Bey, now 63, has rarely hurt for recognition.

He’s had shows at the National Portrait Gallery in London, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Detroit Institute of Arts; Minneapolis’ Walker Art Center toured a survey of his work in the ’90s, his iconic portrait of Barack Obama was included in the 2014 Whitney Biennial, and “Harlem USA” was restaged in 2012 by the Art Institute of Chicago.

Still, becoming a 2017 MacArthur Foundation grant winner, he said, buys time: “I have more ideas than time, and this allows me to focus intently.” It also comes at an unusual point in his career. Though a sense of history lingering always pervaded his work — “Birmingham: Four Girls and Two Boys,” a 2013 project that marked the 50th anniversary of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Alabama, paired children who were the age of the children who died with elderly who were the age they would have been had they lived — the images were often faces and figures. But lately, Bey has been traveling to Ohio to shoot the pathways and safe houses of the Underground Railroad.

“It’ll be nighttime landscapes, showing a sense of place, so very different for me,” he said. “There will be no people in the pictures, and yet there will be, in the sense that it’s spaces where people once moved through. I don’t know if anyone will see this work and immediately recognize it as mine but I like that. I’m in a new period, and it feels good.”

- "Photographer Dawoud Bey adds MacArthur genius grant to noted career looking at African-American life", Christopher Borrelli, Chicago Tribune, October 11, 2017

http://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/ct-ent-dawoud-bey-macarthur-genius-grant-20171011-story.html

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Recipient of a prestigious 2017 MacArthur Fellowship (known as the “Genius” award), and Professor of Art and Distinguished College Artist at Columbia College, Chicago, Dawoud Bey has enlisted photography for over four decades to insightfully portray African-American individuals and communities, and thereby give their presence and narratives greater visibility in the public sphere. Among today’s best known artists to employ the camera, Bey counts among his early influences photographers who focused on people. These include James Van Der Zee and Roy DeCarava, two earlier 20th-century African-American photographers who worked in Harlem in New York, and Mike Disfarmer, whose Arkansas farming community portraits hang nearby.

Bey is perhaps best known for his later half-length, multi-panel portraits in which his sitters pose before vivid backgrounds of powerful color. In contrast to these later works, Bey began his career in the street photography tradition, which relies on chance encounters that result in more spontaneous though still artistically deliberate compositions. His 1975 portraits of Harlem residents in this vein were shown as a group at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1979.

Bey’s three works on view here from a few years later can be seen continuing this earlier strain in the artist’s work. The trio forms a poignant, intimate, sometimes gently humorous and always affecting look into the experiences of African Americans at differing stages in their lives. Bey uncannily portrays them as both individuals and in relation to their family and/or social structure. Apparently aware of the camera, yet not always addressing it head-on, Bey’s subjects engage in various modes of self-presentation, while also consciously or unconsciously interacting within the social milieu in which they live. Bey’s ability to unsentimentally capture the vulnerability as well as self-assurance of people—younger or older—has been apparent throughout his career. A notable later series of Bey’s involved high school students who actively engaged with the artist in telling their own stories in word and image. Bey’s portraiture, whomever it pictures, consistently demonstrates a rare talent in creating richly visual and perceptively commanding works of art, as is evident here.

- Crosscurrents, 2018