Losang Samten

Tibetan, 1953-

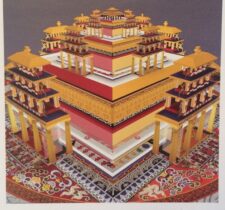

Kalachakra (Wheel of Time) Sand Mandala, 1996

colored sand

38 in. diameter

SBMA, Gift of Friends of Asian Art

SC.2019.1

"The colors and designs of each mandala have profound meaning originating in the ancient teachings of the Buddha, and have remained identical to these original teachings over the centuries, with each color being an antidote to specific negative emotions."

- Losang Samten, http://www.losangsamten.com/mandalas.html

RESEARCH PAPER

In Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism, the Kalachakra Sand Mandala is a two-dimensional representation of the five story palace of the deity Kalachakra. It is made of dyed sand that is applied using a pair of elongated metal funnels called chakpus. One contains the sand and is held in the left hand, which guides the trickle of sand onto the surface. The other is scraped against the corrugated surface of the first to disgorge the stream of sand by vibration. A second tool, the shinga, is a wooden scraper used to straighten edges and remove unwanted sand. The sand is held in place solely by gravity. Fourteen colors of sand are used: white, black, and three shades each of blue, red, yellow, and green.

The palace consists of an ascending sequence of square floor spaces, each nested within the one below and representing the next higher story of the palace. From bottom to top they represent five key concepts that must be mastered on the path to enlightenment: body, speech, mind, wisdom, and bliss. The palace rests on a series of six concentric rings radiating outward and successively representing the elements of earth, water, fire, wind, space, and blazing consciousness, or in the words of the Dalai Lama, "pristine awareness".

The mandala is constructed in two phases. First a detailed outline is drawn from the outside in on a solid wooden platform that has been consecrated in three phases: requesting the site in prayer, purifying the site in a sequence of rituals, and protecting the site through an elaborate ritual dance. The outline is made by snapping chalk strings that have been blessed for the occasion. The mandala may be of any size, but the proportions of the components are extremely demanding. The distance from the center to the outermost boundary of the palace is divided into 13 equal parts by making successive approximations with folded paper until an exact fit is found. That measure, the gho-sted, is then divided into six equal parts to produce the chachung, the basic unit that defines the measurements of all of the structural boundaries within the mandala. Once the detailed outline is completed, grains of wheat are laid out to indicate the placement of the deities that will occupy the palace.

The mandala is then painted from the inside out. The elaborate structure is adorned with a complex array of deities, animals, flowers, offerings, balconies, portals, seats, wheels, geometric shapes, Sanskrit syllables, and other esoteric references to scripture. The design, which dates back over 2,600 years to the Buddha himself, contains within it, in symbolic form, all of the instructions necessary for the attainment of enlightenment. The artist monks, who have typically had four years of education and training as well as many years of progressive experience, perform their task entirely from memory. Every element is specific as to color and form. Moreover, since each detail of the mandala faces the central deity, the monks are painting entirely from an upside down perspective.

SBMA was given a special dispensation for an educational Kalachakra Mandala that differs in three ways from the traditional version discussed below. It has only the top three floors of the customary five story palace. Some of the central layers have been elevated to bring out the appearance of three dimensionality. It has been glued down and preserved rather than ceremonially dismantled.

A sampling of the intricate symbology follows. The senior monk enters from the East (bottom) and paints an eight-petaled lotus with a five-layered platform in the center. The five layers symbolize respectively the lotus flower (letting go of attachments), the moon (pure nature that calms emotions), the sun (realization of emptiness), the head of the dragon Rahu (wisdom of immutable bliss), and the tail of the dragon Kalagni (empty form). Only the top layer is visible. This provides a cushion on which sits Kalachakra, represented by a blue vajra, a ritual implement used in tantric practice to cut through illusion. The curvilinear line represents his cloak. Seated next to him is his consort, Vishvamata, represented by a yellow dot indicating the earth element. Each petal of the lotus supports a goddess represented by a colored bead. In each case the simple bead stands for a much richer iconography. For example, on the southern (leftmost) petal is visualized the red goddess Raktadipta, having red, yellow, white, and blue faces looking in the four directions, and eight hands, holding in her right hands a butter lamp, string of pearls, crown, and bracelet and in her left hands a garment, belt, earring , and anklet. A blue background is painted around the lotus and in each corner a dot is painted in a specific color to represent the body, speech, mind, and wisdom of the deity. Finally, the highest floor of the palace is encased with two square, light blue borders in which the intervening space is filled with a chain of black vajras that represent beams supporting the ceiling. This is but a tiny fraction of the entire mandala, all of which is equally intricate and rich in symbolism.

A team of four monks next continues painting outwards, descending through the remaining floors of the palace, each responsible for one quadrant. They will later be joined by four more monks as the perimeter enlarges and space permits. For large mandalas, there may be as many as twelve monks by the time they get to the outermost ring of elements. The monks do not express any individuality in their work but, rather, commit to achieving perfection in the execution of every traditional detail.

Kalachakra is roughly translated as "wheel of time". Kala is Sanskrit for a concept of all-encompassing time that contains past, present, and future in a single, directionless field, somewhat like our concept of space. Chakra translates into wheel and represents cycles of time that continue endlessly. While unenlightened individuals struggle with change, notably the awareness of the passing of time, of loss, of aging, of sickness, and of dying, the Kalachakra deity is not attached to worldly phenomena, does not suffer change, and is therefore thought of as an omniscient guide to meditative awareness. In support of this goal, a host of subordinate deities, 722 in all, identified in the mandala by symbols, dots or Sanskrit syllables, serve as objects of meditation that are of assistance to the viewer. The viewer approaches enlightenment by imagining himself to be Kalachakra and the entire host of subordinate deities simultaneously.

The primary purpose of the Kalackakra mandala is to provide a visual framework for the Kalachakra Initiation, a ceremony in which monks and nuns take vows to pursue the bodhisattva path to enlightenment [see Postscript below]. The mandala is painted throughout the course of the ceremony and is dismantled at the end. The deities are picked off one by one by the head monk as he recites the Kalachakra mantra. The sand is then swept to the center of the mandala and placed in an urn. The urn is carried in a procession to a large body of water where the monks pray for the protective spirits of the water to accept the consecrated sand for the benefit of all beings. The dismantling is viewed as a lesson in non-attachment that recognizes the impermanence and transitory nature of all aspects of life.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Mike Ramey, June, 2014.

Bibliography

Berzin, Alexander. Introduction to the Kalachakra Initiation. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications, 1997.

Bryant, Barry. Wheel of Time Sand Mandala. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1992.

Gyatso, Tenzin, the Dalai Lama and Jeffrey Hopkins. Kalachakra Tantra Rite of Initiation. London: Wisdom Publications, 1985.

Mullin, Glen. The Practice of Kalachakra. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications, 1991.

Samten, Losang. Losang Samten. Website, 2014.

http://www.losangsamten.com/

Thurman, Robert, Editor. Kalachakra for World Peace. Washington: Capital Area Tibetan Association, 2011.

POSTSCRIPT

THE KALACHAKRA INITIATION

The Kalachakra Initiation is an 11 day public ceremony in which a vajra master, often the Dalai Lama, transmits an oral tradition to monks and nuns that empowers them to comprehend the state of mind of the deity. Three principles are personified in Kalachakra: renunciation, bodhicitta, and emptiness. Renunciation is the cessation of the suffering of attachment to either the material or experiential world, such distractions as the desire for pleasure, gain, fame, or praise and aversion for pain, loss, blame, or disgrace. Bodhicitta is predicated on the Buddhist belief in reincarnation and centers on a vow to remain of service to others on earth through countless lifetimes until all sentient beings are enlightened. Emptiness does not mean nothingness. It means empty of inherent existence, or, put another way, that all phenomena are dependent upon prior causes and conditions.

After a number of preliminaries, the initiates begin their journey of visualization by entering the mandala through the eastern gate. They circumambulate the mandala three times blindfolded. At each gate they make prostrations and intone mantras that welcome specific deities to dissolve into their bodies, allowing them to serve and please each one. The disciples make supplication to the lama for the descent of the wisdom of Kalachakra. The lama places lotus flowers on their heads. Nectar flows from the flowers purifying obstacles to the attainment of enlightenment. They remove their blindfolds, open their eyes, and see Kalachakra in radiant light, thereby clearing away all accumulated negativities. Kalachakra is visualized having four faces. The one facing east is blue black and wrathful. The one facing north is white and very peaceful. The one facing west is yellow with a look of meditative concentration. The one facing south is red, with an expression of desire. His three-tiered crown is topped with the seal of the bodhisattva Vajrasattva. His body ornaments include vajra, jewels, earrings, necklace, bracelet, belt, ankle bracelets, flowing scarves, garlands, and a skirt of tiger skin. He has 24 arms, each holding a different ritual implement. The disciples are now ready to receive the first of 7 initiations.

The Water Initiation begins at the northern gate and is analogous to washing an infant immediately after birth. Using a conch shell, the lama sprinkles the initiates with water taken from purified vases. A ray of light from Kalachakra's heart draws the initiates into his mouth, through his body, and into the womb of Vishvamata. Offerings are made and the initiates radiate back to their seats at the northern gate. Their five bodily elements (space, air, water, fire and earth) are generated into five mothers located at the crown, forehead, throat, heart and naval chakras. Light radiates from the five mothers in the bodies of the disciples and draws from the mandala replicas of their counterparts there. The stains of the five bodily elements are washed away and the initiates are granted the ability to achieve positive potential.

The Crown Initiation is also performed at the northern gate and purifies the five aggregates: form, feeling, perception, the unconscious, and consciousness. The disciples then perambulate to the southern gate for the Silk Ribbon Initiation, which purifies speech. The Vajra and Bell Initiation is also given at the southern gate, and represents the union of compassion and wisdom. The procession then returns to the eastern gate for the Conduct Initiation, which clears away defilements from the sense powers and their objects. The Name Initiation follows, to purify the faculties of action and activities (mouth, arms, legs, and groin). The procession is then lead to the western gate for the Permission Initiation, to cleanse the pristine consciousness with the five hand symbols (vajra, sword, jewel, lotus, and wheel).

Taken together, the seven initiations clear away the defilements of ill deeds and authorize the disciples to cultivate achievements, set potencies for the collection of merit, and grant practices and feats related to the highest pure land. The disciples can now say the final mantra with the pride of being the deity.

OṀ SARVATATHᾹGATA SAPTᾹBHISHEKHA SAPTABHŪMI PRAPTO ʻHAṀ

"Om, through all the Ones Gone Thus manifestly bestowing the seven initiations I have attained the seven grounds."

[Om is a Sanskrit seed syllable found at the beginning of all mantras and indicating that a sacred text is to follow.]

http://www.cs.cornell.edu/~kb/mandala/main.htm