Unknown

Roman

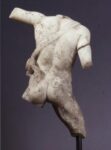

Achilles and Troilos, 2nd c. CE

marble, white

20 x 16 1/2 x 8 in. and 12 1/2 x 9 x 4 in.

SBMA, Gift of Wright S. Ludington

1992.37.1a,b

RESEARCH PAPER

The Myth

Ancient Greek Man created God in his own image. Greek gods quarrel, envy, play favorites, take sides, play tricks, hold grudges, seduce and prey, cheat, make bargains, exact revenge.

And, they meddle.

This sculpture tells a story, and the story begins with gods fighting over an apple. Slighted for not being invited to a wedding, Eris (goddess of strife!) tosses a golden apple labeled “to the fairest” in the midst of Hera, Athena and Aphrodite. Called upon to settle the inevitable dispute, Paris, son of Priam, King of Troy, picks Aphrodite after she bribes him with the promise that Helen, the fairest of mortals would be his. Paris of Troy steals Helen of Sparta, and the Achaeans (1) launch a thousand ships, and lay siege to mighty Troy.

The war is long, costly and cruel, and gods take sides. Slighted by the Judgment of Paris, Athena is on the side of the Greeks. Apollo on the other hand, angry that Agamemnon (2) snatched the daughter of a priest of his, sides with Troy.

Troilos (3) is a beautiful adolescent, the youngest son of Priam, the king of Troy (although he is in fact thought to have been fathered by Apollo,) and Hecuba, and therefore a brother of Hector and Paris. The oracle prophesies that Troy will not fall if he lives into adulthood. Achilles is a fearsome Greek warrior, anxious to capture Troy and end the war. The goddess Athena urges Achilles to seek and kill Troilos, thus avoiding the prophesied survival of Troy. The stage is set for the violent encounter depicted in our extraordinary marble sculpture.

Being a non-warring adolescent, Troilos is safe close to home. But he takes great delight in his horses, and one day rides with his sister Polyxena and her water jug to a well in Thymbra outside the walls. Aided by Athena, Achilles ambushes him, drags him off his horse by the hair, pursues him into the nearby temple of Apollo and slays him at the altar. The sacrilege will later cost Achilles his life, as an angered Apollo will reveal to Paris that, to be lethal, Paris’ arrow must strike the Achaean’s only soft spot, his heel. In one version of the story even, Apollo personally guides the arrow to the Achillean ankle. (4) (5)

The Piece

The modestly sized group of Achilles and Troilos is sculpted out of white marble. In its present state it consists of two discrete fragments; a standing male on the left leaning slightly to his right while reaching with his left arm toward a second male figure, which is seemingly in the process of dismounting a horse. Missing are the men’s heads, most of the horse’s tail, and, with the exception of the rider’s fairly intact left arm, parts of the limbs of both the men and of the horse.

The horse is rearing on its (for the most part missing) hind legs, which would have been resting on an also missing base. Holes in the stubs of the horse’s otherwise unsupported forelegs indicate that at some point pins in those spots held those missing limbs, probably following a repair after the vulnerable extremities broke off.

In addition to the rear legs, a cylindrical member, sculpted to look like an incidental tree trunk, “grows” from the “ground“ and rises to support the mass of the horse and rider. The rider’s right leg, airborne and therefore structurally fragile, is braced onto this “trunk,” as the missing left leg would likely also have been. It is inevitable that the main support would be visible, which is why it’s made to look like a tree stump. The braces are positioned so that they can be credibly out of sight. The horse is saddled by means of two lion-skins the heads of which meet mouth to mouth at its chest.

Dating antiquities is an approximate and tenuous business, and in this case even SBMA references clash somewhat. Our Achilles-Troilos Group is generally labeled to be from the 2nd c. CE, but in the Del Chiaro, 1985 exhibition catalogue it is referred to as of “the second century B.C.” This could be a misprint (B.C. instead of CE), but R. R. R. Smith and C. H. Hallett, in the Journal of Roman Studies speculate that the “…date is clearly not second century B.C., more likely third or fourth century A.D.” It is in any case generally agreed that this artifact is a Roman copy of a late 4th c. BCE Hellenistic original.

Its modest size suggests that it was meant to be displayed on a raised support (such as a tabletop or plinth.) The care taken to craft and detail all sides suggests that it was intended to be seen in the round, presumably enjoyed and ostentatiously displayed by a wealthy, cultured Roman citizen or official. It is believed to be from Asia Minor, and its style suggests that it is very probably the work of a sculptor of Aphrodisias, where the miniaturization of famous statue-groups of which full-size versions are known to exist in the city is a common phenomenon. (6)

It is fair to pose two questions about the piece: how do we know that the two fragments belong together, and how certain can we be that they depict these particular actors of this particular legend acting out this particular event of mythical violence? Regarding the grouping of the two fragments, in addition to the basic facts and similarities (discovery, type of material, scale, gestural and postural formal relationship…), the tell-tale evidence is sculpted on the back of the standing figure. Behind the warrior’s empty scabbard, at just the right spot, is a form that is in fact the tip of a horse’s tail. Mentally filling in the missing parts we thus find our Achilles linked with a tuft of hair not only with the unfortunate young Troilos, but also with Troilos’ diminutive horse.

That these figures are indeed Achilles and Troilos is credibly surmised by the postural relationship of the horse and men, details like the lion skin blanket typically shown on Troilos’ horse, and the popularity of sculptural, painterly and particularly ceramic depictions of the myth throughout the Greco-Roman world (and even earlier, such as Etruscan.)

Action driven mythical and heroic subjects were generally popular, but there is no general agreement as to the reason for the broad popularity of this particular theme. Credible arguments are that it’s because this singular event foreshadows both the fall of Troy and the demise of the major heroic figure of Achilles; because of the elements of extreme hubris and sacrilege and their punishment; because of the melodramatic nature of the brutal slaying of a young non-combatant; and even because of the somewhat pederastic assurance that the beautiful boy would never grew old and ugly, preserving his youthful image for all eternity. Perhaps the confluence of many or all of these reasons ensured the appeal.

The Santa Barbara piece therefore shares similarities with many examples. However, it also possesses certain unusual features, some arguably unique. For one thing it is a piece of sculpture, and in the round at that. Some other sculptural examples exist but few if any are meant to be enjoyed from all sides, and for most part this theme is much more often depicted in pottery or relief.

Less common is the depiction of Achilles not in full armor, specifically not carrying his famed shield. This seems minor, but we can argue that this is a gesture of realism that distinguishes it from artworks that adhere to stylization. A powerful armed warrior ambushing an unsuspecting unarmed adolescent astride a horse does not need a shield. He needs a free hand with which to pull the youth down, and a hand with a sword in it with which to slay him. An artist depicting this scene in the more popular version, with Achilles in a helmet and shield, does so because “that’s how warriors are drawn.”

Arguably unique to this piece, is that the Troilos figure is a) large in scale, and b) depicted not astride the horse but with both legs on its side as if he is in the act of dismounting. How could this be, if he’s suddenly being pulled off a horse? And in all other depictions the figure of the adolescent Troilos is always smaller than Achilles’; here it is essentially the same size and has a similar adult muscular structure. There’s speculation that this indicates versions of the myth where Troilos is not a passive youth but a brave warrior who is responding to the ambush by dismounting, and that, were the right hand intact we would be seeing it grasping a sword. I believe that the sword conjecture is off, since there’s no scabbard, and the sculptor paid so much attention to the furnishing of a detailed one for Achilles. I tend to believe that both Troilos’ posture and scale are aesthetic choices; in this way the massing of the group is visually better balanced, and we are presented with the preferred full frontal view of two naked males than with the unceremonious and half-hidden side view of one of them. (7)

Speaking of Aesthetics

Largely intact, well preserved and minimally restored, this exquisite acquisition is a finely crafted example of Hellenistic sculpture. The articulation and grouping of relatively complex masses is masterful, as is the modeling of beast and men. It is a violent scene that we mentally reconstruct, yet we can imagine the delicate finesse involved in the two otherwise hard and heavy masses of the composition being delicately joined by the flowing tail of the horse. We feel the powerful bracing and muscular power of Achille’s firmly planted right leg, the violent twist and jerk of Troilos’ neck, enough to fling him off his leonine saddle, his tight and desperate grasp of the reins, the energy latent in the entire motionless stone complex.

A final note, as we contemplate the polished and pure white marble: in the crevices of the supporting “tree trunk” we see remnants of reddish pigment, reminding us that the ancients painted the entirety of their sculptures. And so we begin again to mentally reconstruct and reimagine anew…

Notes:

(1) Name of ancient Greeks much more commonly referenced in the Homeric epics of the Trojan war.

(2) Commander of the Greek armies.

(3) To the Romans, Troilus.

(4) More background on Achilles: He was the son of the Nereid Thetis and of Peleus. Thetis was the daughter of sea-god Nereus. After Peleus and Thetis married, the ladies of fate (oracles) prophesied that their son was destined to die in battle outside the wall of Troy. Thetis tried to make Achilles immortal by holding him by just one heel and dipping him in the river Styx, which made tiny Achilles virtually invulnerable. His only weakness was his heel which had no contact with sacred river water. Hence the term Achilles heel to express a weakness or vulnerable point.

(5) This is the basic, most common telling of the stories of The Judgment of Paris, Achilles and Troilos, and Achille’s death. Greek mythology is rife with variations.

(6) The provincial capital of the Roman Caria in western Asia Minor. Marble sculptures and sculptors from Aphrodisias were famous in Roman times. A stunning blue-grey marble horse with a white marble rider, found in the Basilica at Aphrodisias, has also been identified as depicting the mythical Achilles and Troilos ambush.

(7) And in doing so our sculptor now chooses to sacrifice realism to serve aesthetics.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Marcos Christodoulou, 2020.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Del Chiaro, Mario Aldo. SBMA exhibition catalogue, “Classical Art Sculpture.” Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1985.

Smith, R. R. R. and Hallett, C. H. “Troilos and Achilles: A Monumental Statue Group from

Aphrodisias.” Article in The Journal of Roman Studies, August 2015.

Graves, R. (1955) “The Greek Myths.” Penguin Books, 1990 printing of the 1960 revision

Daehner, Jens. “Art Matters Lecture Series: (Pt. 1). October 2017.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COzS_i6wXgw&t=3029s

COMMENTS

Hellenistic original; probably from Asia Minor

This active and relatively small figured group is comprised of two male figures and a diminutive horse - the standing figure detached, the horse and rider in one piece. The entire group was doubtlessly set on a single plinth (base), and, consequently, the standing figure would have been placed higher and closer to the mounted figure than now. Although the rider appears to be dismounting with his body turned toward the standing figure, he is actually being pulled off the horse by his hair, which was originally grasped in the left hand of his adversary. Evidence for such reconstruction is offered in a stereotyped pose already well known by the late fourth century B.C. - especially in scenes depicting the struggle between the Greeks and the Amazons (women warriors). The theme of rider dragged off his or her horse became a popular one in Greek as well as Etruscan art.

The rider in the Santa Barbara group, naked but for vestiges of a mantle clasped around his neck and shoulders, grips the reins tightly with his left hand as he is unceremoniously pulled from his mount. Despite the fact that the head of the rider is altogether missing, one can sense the violent backward twist of the head.

Although it is difficult to ascertain what, if anything, was originally held in the now missing right hand of the rider , the corresponding hand for the standing figure must have unquestionably held the sword drawn from the now empty scabbard that rests high at his left side, suspended from a broad strap that runs diagonally across back and chest and over the right shoulder. The strap itself is decorated with a narrow strip along each side and a series of circular, disklike forms set about 5 cm apart.

The undersized horse, displaying a double-cropped mane and tousled forelocks, is "blanketed" with a double lion-skin, the heads of which meet mouth to mouth at the horse's chest. The legs and paws of the lion-skin dangle at the horse's hind and shoulder quarters. Beneath the belly of the horse, a tree trunk serves as a support for both horse and rider, whose disproportionately large left foot rests flat against the lion-skin at the left flank of his mount. That this lively group does not refer to an Amazonomachy (battle of the Greeks and Amazons) is quite obvious from the sex of the two figures. If the rider, who seems to be attacked as he is about to dismount, can be regarded as Troilos, and the aggressor as the Greek hero Achilles, then the sculptural figured group represents the popular Homeric tale of the ambush and death of Troilos. According to prophecy, beseiged Troy would never fall as long as the youngest son of the Trojan king Priam survived. Because of this one can better understand why such a heinous mismatch as that of the Greek warrior Achilles against the youthful Troilos was acceptable to the ancient Greeks.

On the evidence of the horse type (long neck, small head with its prominent eyes set into a clearly articulated bony structure, small upright ears, flat cheeks, gaping mouth and distended nostrils, and double-cropped mane with contrasting forelocks) and its lion-skin covering, and the appearance of both Achilles and Troilos as nude figures, Asia Minor more than elsewhere in the Hellenistic world is likely its area of origin. During the second and first centuries B.C., such small sculptures-- perhaps conceived as table-top decorations or as small garden pieces to be viewed in the round--would have appealed to cultured persons or buyers. Interestingly, the Asiatic horse type in this Achilles-Troilos group finds its closest parallels in monuments created in Asia Minor.

In view of the typology of the horses, the parallels in stereotyped pose, and the chronological association as early as the second half of the fourth century B.C., I believe that the Santa Barbara Achilles-Troilos Group was produced for an educated, upper-class client by an Asia Minor sculptural workshop during the second century B.C., strongly influenced by earlier, late-fourth-century models.

- Maria A. Del Chiaro, SBMA exhibition catalogue, Classical Art Sculpture, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1985.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

One story from the Trojan war stated that the city of Troy could never fall while its youngest prince Troilos was still alive. Wanting to ensure success for the Greek side, the hero Achilles ambushed and killed the prince outside the city walls. Many images of this event exist in different media and it is likely that this sculpture is a miniature version of another more monumental example. In most other depictions, Troilos is shown smaller than Achilles, demonstrating the relative importance of the Greek hero in the broader story of the war. Here they are the same size, indicating an interest in promoting the Trojan prince in the story from a boy to a warrior in his own right.

- Ludington Court Reopening, 2021