Unknown

Chinese

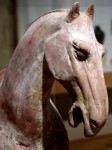

Standing Horse, 618-906 CE, Tang dynasty

buff earthenware with traces of pigment

22 1/2 × 25 × 7 in.

SBMA, Gift of Robert B. and Mercedes H. Eichholz in honor of C. Ann Booth

1992.15

RESEARCH PAPER

With tilted head, wide open eyes and nostrils taking in all there is to see and smell, and raised foot, this clay horse figure looks alive and in motion. The attention to details seen in this figure, its precise proportions, and realistic representation of the muscles and bones exemplify the highest aesthetic standards for realism or naturalism, which typify the arts in China’s Tang Dynasty (618-906).

The History and Meaning

The horse is both a religious and political symbol. As the “heavenly horse”, also known as Ma-Wang, it was the symbol of the life force in the pre Buddhist and early Buddhist theology. Having better horses enabled the Han Dynasty emperors to unify China, so this horse was also the symbol of the power and authority of the court.

Religious symbolism

From the pre Buddhist theology that was brought to China from India, the metaphor used to describe the cosmos was the configuration of the horse. For example: the back of the horse represented the heavens, the underbelly: the earth. The head was the sunrise, and the eyes: the sun. The rump sags down like the setting sun. The four flanks represented the four cardinal directions, the limbs: the seasons, and the joints were thought to represent the months. The bones are the stars, and the flesh: the clouds. But most significant: the horse’s breath was thought to be the wind or life force; and fire essential to life comes from its open mouth.

When we see the SBMA Tang horse so alive and in motion, we “see” the life force or Ch’i.

As this pre Buddhist concept about the horse was adopted into Buddhist theology, it took on even more meaning because the Shakyamuni Buddha was said to be born in the year of the Horse. Consequently, the zodiac years of the Horse are believed to be the most auspicious times. Parables about the behavior of Buddha’s horse, Kamthaka, are used to help believers to be aware of the need to keep a constant balance between their inner wild nature and their duty to others: even as the wild horse is tamed for human use, it is still wild.

Cultural symbolism

Since before the Shang Period (1766-1122BCE), China had horses. They were depicted on cave and tomb walls as short legged, 12 to 13 hands high (4.5 feet) to the shoulder, stubby creatures that looked much like mules or ponies. Even this early, the Chinese used the horses domestically rather than simply hunted them as prey. The great mythical first Emperor Yu (around 2250BCE in Neolithic times) is thought to be the first to use horses rather than cattle to pull his cart: so the Chinese are credited with inventing the harness.

It was in the Han Dynasty (206BCE to 220) that images of horses portrayed on tomb walls changed, and the image of the elegant refined “heavenly horse” began to appear. Though Emperor Qin Shi Huang Di had begun the unification of China, barbarian peoples were still invading the remote grassland regions. As the military campaigns were sent to recapture these remote regions, the generals heard rumors of superior long legged and lean horses; 15 to 16 hands tall (about 5.5” to the shoulder or withers) with aristocratic faces, short manes, and no feathers at the legs. They were described as quiet tempered but alert and quick to arouse and so strong and noble and that they “sweated blood”. (These are the ancestors of the Akhal-Teke: Turkmenistan Horses. It was known they were being bred near Fergana, Bactria, which is now Afghanistan).

The Han Emperor Wu (141-87BCE) wanted these superior horses so he could dominate and control the barbarians, but also he believed such mythical horses could carry him to heaven. So they were named the “heavenly horses”.

He purchased over 500 of them in exchange for silks, jade, ceramics, and fine filigree bronzes. This trade marked the beginning of China’s role in the trade activity on the “Silk Road.”

By the Tang Dynasty (618-906), when the SBMA Standing Horse was made, the Emperor was said to have over 700,000 horses. Owning a horse meant having power and authority. So all the courtiers wanted to own them or have replicas (mingqi) of them in their tombs. So the Tang artists not only portrayed them with unprecedented naturalism, but also symbolically with one leg ready to go: alluding to being able to “dance for an Emperor”; and with their head cocked and nostrils flared to show their great power, and energy.

By the middle of the Tang Dynasty, horses were used by courtiers for recreational activities too like riding, hunting, and playing a game like “polo” which had been imported from Persia. (This can be seen in the figure of the SBMA Falconer in the other Tang Case(?)).

It is important to note, that while courtiers valued this symbol, no great Confucian scholar or statesman would have agreed. Instead of the horse, the donkey was the symbol of the scholar and when scholars are presented as riding in the Classical Chinese Paintings from the Song (960-1279CE), Chin or Jin (1115-1234), Yuan (1280-1368) and even the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) they are usually riding donkeys.

How it fits in the History of Chinese Ceramics

Ceramics have been important throughout 45 centuries of China’s history. While many other cultures had developed ceramics for utilitarian purposes, the Chinese started created pieces with unique stylistic traits even before the Shang Period (1766-1122BCE). The combination of the development of the smoother kaolin clays and the discovery of glazes in this Period allow some scholars to say that the production of artful ceramics in China predates similar wares in the West by 2,500 years. (see #4, page 132)

Because they were so unique by the times of the Han Dynasty, these artful Chinese ceramics were as valued in the West as silks, jades, and bronze filigree. Then, with the great expansion of wealth and demand for the refinement by an ever more sophisticated court; ceramic arts reached a golden age during the Tang Dynasty. Even lesser court officials and persons of modest wealth could collect and own these clay figures.

Material and Technique

The SBMA Standing Horse was first formed by the sprigging together of molded parts. You can see a fine dark line where the neck and body are joined and between each leg and the body. A fine orange colored partial kao-lin clay mix, low in metallic particles, that distinguish clay works of the Tang period, was pressed into the base molds and diluted for use in the finish coat. This finish layer was spread over the mold parts to hide the joints. This terracotta-tinted slurry can be seen both on the neck and on the rump,

Then, rather than use either the bold tri-colored or bright white glazes which distinguish Tang Ceramics and can be seen in many of the other SBMA Tang clay figures, a thin layer of wet clay and white or buff powder was spread on the surface and scraped with many short strokes. This was probably to replicate the short hair coats of the fine Fergana horse it represented.

Finishing it this way may have made it look more realistic, but it also may have served to recall the myth that when these golden-red horses were covered with sweat from exertion, their coats seemed white, and as they reflected the sky they could not be told apart from heaven.

Over this coat, in some places there are lumpy deposits of coarse material, which appear to have adhered to the white layer and were left on in restoration so as not to obliterate the underlying white finish. These may be remnants of soil found on the figure as it was recovered from its burial in a tomb. Seeing remnants of this soil layer left on allows the viewer to contemplate the time and place where this great horse was found and the delicacy of the process of recovery and restoration of fine art pieces from such ancient times.

Style

Upon first view of the mass, it seems improbable that such fine thin legs could support such a thick dense body and large neck and head: especially with one leg lifted. Then on closer examination, it is clear that the backward sway of the rump and the offsetting the tilt of the neck and head with the lifting of the opposite leg makes the balance work.

Each of these features: it’s size, the sophistication of its composition, and detail, exemplify the highest of technical skills for making these clay figures. This distinguishes the ceramic arts of the Tang Dynasty Period.

The unusually large size of the horse, the unique finish and the incredible balance that has been created to allow it to stand upright all celebrate the special craftsmanship it took to make this magnificent Horse.

Prepared for the Docent Council by Gail Elnicky: July 2004

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Boulnois, Luce as translated by Helen Loveday. Silk Road; Monks, Warriors

and Merchants on the Silk Road. New York: W.W. Norton and Company,

Inc., 2004.

2. Harrist Jr., Robert E. Power and Virtue: the Horse in Chinese Art . New York:

China Institute Gallery, 1997.

3. Hean-Tatt, Ong. Chinese Animal Symbolisms. Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia:

Pelanduk Publications(M) Sdn. Bhd., 1997.

4. Jacobsen, Robert D. Appreciating China. Minneapolis, Minnesota: the

Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2002.

5. Juliano, Annette L. Bronze, Clay and Stone: Chinese Art in the C. C.

Wang

Family Collection . Seattle: University of Washington Press and Hsi An

T’ang,1988.

6. Lee, Sherman, Editor Curator. China, 5,000 Years. New York: Harry N.

Abrams for the Guggenheim Museum, Inc., 1998.

7. Medley, Margaret. The Chinese Potter; A Practical History of Chinese

Ceramics. London: Phaidon Press Limited,1999.

8. The World Book Encyclopedia: Volume H. Chicago: World Book, Inc. 1999.

WEB SITES:

www. asia.society.org

www. english.people.com