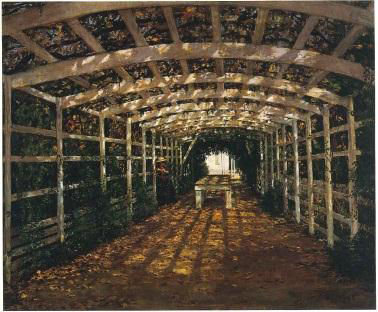

Alexander Harmer

American, 1857-1925

Arbor at Rancho Camulos, 1886

Oil on canvas

25 x 30"

Estate of Helen Padotti

TR 3150

“…eulogist of the beauties of the world.” - Alfred Douglas Harmer

COMMENTS

That phrase aptly describes a special person in the history of early California and vaquero art. They were spoken by Alfred Douglas Harmer about his beloved father, and only begin to introduce the artistic and social contributions made by Alexander Harmer, an artist considered to be the first important painter of the West and a leader in California’s art community of the late 1800s and early 1900s. Harmer was a pioneer in the portrayal of not only the “fantasy” of the West but of its reality with his depiction of the plains and its indigenous people. But his most popular contribution must lie within his collected works that celebrated the memories and visions of the people and ways of early California.

Harmer’s love of the early history of California led him to meet one of the most important people he would come across, ironically when he was about to leave California to study once again at the Academy in Philadelphia. In 1888, Harmer became fast friends with Charles Lummis. Lummis shared Harmer’s love of the Hispanic culture of the past days of Alta California and they both held concerns for the restoration of the California Missions. Lummis would go on to be the center of that passion-play and create the “Landmarks Club of California” in 1894 dedicated to the task of rebuilding the missions – and the ethnic romance attached to them. Lummis called upon Harmer to assist him with the publication “Land Of Sunshine” – a magazine dedicated to the mission task that celebrated the area’s prose, poetry and art. Harmer created numerous illustrations and paintings during this period and of his work Lummis said, “Harmer is particularly and undisputedly the artist of the Apaches and the old-time California.”

It was Lummis, who early on, introduced Harmer to the Del Valle family, said to be among the last of the area’s old Spanish families to have retained the “old ways” of their culture. Their ranch, Camulos would be the inspirational setting for Helen Hunt Jackson’s book, Ramona. The reenactments and settings would be the subject of many photographs taken joyously by Lummis and became the fuse that launched Harmer into his most important period. The subject of old California would become the new imagery that would fill Harmer’s work and become an important window on the past that helped define the vaquero culture of California, to this day. Harmer’s work, while widely admired, had yet to see a wide collector base outside the region. With the resurgence of interest in the vaquero culture and of the era’s horsemanship techniques, Harmer’s work has found a new and broader audience, far past the borders of the old Alta California vaquero’s world.

[Now a National Historic Landmark and Museum in Piru, Ventura County, Rancho Camulos is open to the public for docent-led tours Saturdays, 1-4 p.m.]

- William Reynolds, "Smoke Signals," July, 2009