Unknown

Japanese, Edo Period (active Japan)

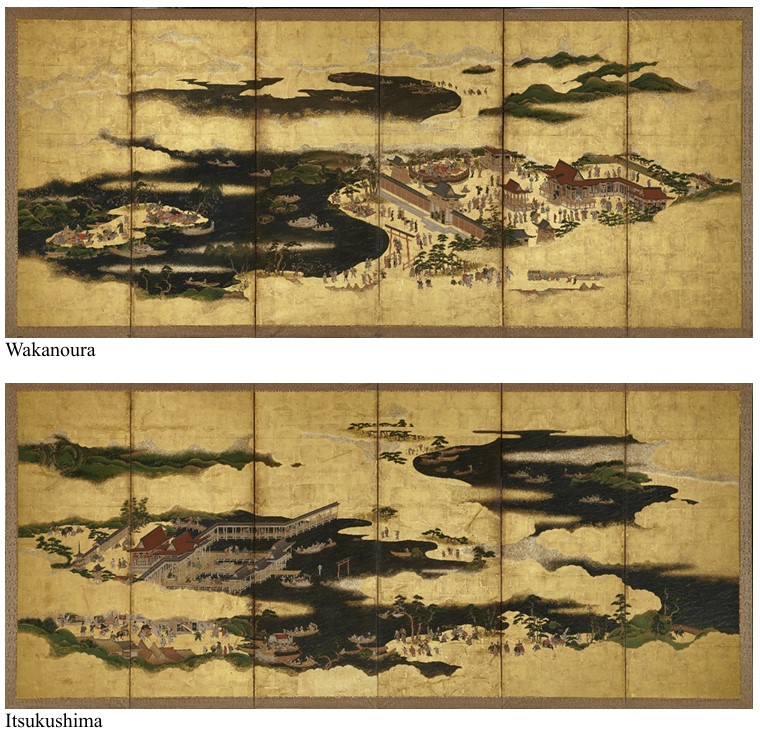

Views of Scenic Sites Itsukushima and Wakanoura Shrines, 17th-18th century

Color and ink on gold leaf; pair of six-panel screens

37 1/2 × 17 1/2 × 73 in.

SBMA, Museum Purchase, Peggy and John Maximus Fund

2017.26.1-2

RESEARCH PAPER

“Views of Scenic Sites Itsukushima and Wakanoura Shrines” are examples of the paintings of famous places (meisho-e) that became a genre during Edo period (1615–1860), when after a century of peace, tourism helped develop a cohesive Japanese culture. The scenic locales depicted on this pair of six-panel screens both feature Shinto shrines, celebrated as early as the ninth century in traditional poetry: Wakanoura on the island of Shikoku and Itsukushima, part of the Miyajima shrine complex on the western end of Inland Sea near Hiroshima. The shrine architecture is detailed enough to date the paintings with known phases of construction and alteration; each features the red Torii gates identified with Shinto, as well as enclosures and gates that reveal the procession toward the inner sanctum. At the bottom of each screen, beneath a cloudlike element that LACMA curator Hollis Goodall (1/20/2019) calls a “device to compress time and space,” one can glimpse the local village where tourists might find lodging, food, souvenirs, and other pursuits.

The compositions are complex and colorful, with sinuous shapes—inlets of water, puffs of clouds and fog, mountain peaks—and the angular forms of architecture, set on a gold ground. The dominant impression created by the gold ground conveys its etymology from a Sanskrit word meaning “to shine, shimmer.” The gold would reflect light, creating a dreamlike atmosphere that contrasts the ever-green pine trees, which convey an enduring character (Goodall 10/3/2018). The addition of cut foil and gold dust “satisfy the insatiable taste for the new and fashionable” (SBMA gallery label, 2024) and “overlays of two-tone cut-sprinkles, kirikane, …indicate that it was created for a wealthy urbanite.” (CollCmt)

The view from above, which seems to be tipped upward without regard to Western concepts of perspective, is in “map style…as if from a drone,” according to Goodall (lecture Jan 20, 2019) During the Edo period artists began to simplify their compositions, to focus on key locations, rather than attempt to depict the entire temple precinct, although Goodall notes that this painter had probably never visited Wakanoura because he depicts the shrine as if it is on the shore, when in fact, it is 100 meters up a steep hill. The portrayal of Itsukushima, which is a shrine dedicated to the protection of fishermen, features many kinds of boats, including ferries to transport visitors to the main sanctuary and the floating stage used for performances of Bugaku, an ancient form of court music and dance.

Although the Kano school developed its characteristic style in official workshops as painters of the shogunate and its sophisticated courtiers in Kyoto, by the late sixteenth century, “The services of these artists were also sought by newly affluent merchants for whom displaying such paintings in their homes conveyed their civic pride and erudition. Based on the liveliness of the figures who are engaged in various activities…these screens were likely to have been painted in a machi-eshi (“town painters”) workshop, where artists created the earliest paintings in the ukiyo-e (“floating world”) style…typically unsigned…eclectic in subject and style, with innovative compositions.” (Graham)

An amalgam of genre scenes depicting festivities on temple grounds engage the viewer in the life of the period. The left half of the Wakanoura screen is occupied by revelers picnicking under the cherry blossoms of spring, fishing, and floating on party boats. Inside the first gateway, within the outer precincts of the shrine, a dancer (perhaps a geisha?) is entertaining a circle of admirers behind a cloth enclosure, while others peer through gaps in the barricade, catching a glimpse of the “floating world,” in a scene that seems lifted from period ukiyo-e.

Different classes of people can be differentiated by costume: courtiers in tall black caps; monks in brown robes; samurai carrying swords; nobles on horseback; commoners, including porters with bare legs, hoisting heavy loads; children scampering. In the inner precincts of temple grounds, the domain of the kami (Shinto gods), only the elite were permitted entry, so the latest fashions are displayed on the figures therein. Figures on horseback are centered in the tourist villages at the bottom of each screen, and a lone horseman, perhaps a sentinel, is the sole figure on the right panel of the depiction of Itsukushima.

The Japanese term for such screens is “byobu,” which literally means, “to stop the wind” (Goodall 2018): these were furniture as much as paintings, room dividers that were foldable and portable. Their structure surprises visitors, who assume they are panel paintings, according to SBMA docent Denise Klassen; in fact, explains Kyoko Sweeney in her research paper (2002), “Each panel is made of a light wood frame surrounding a latticework interior covered with several layers of paper. Over this foundation the painting is mounted. Real gold is used for the gold background: to make a very thin gold leaf, gold sheet about 3 inches square are placed between papers and pounded carefully. The paper surface is painted red to give the gold a richer tint and the gold leaves are glued to the paper with animal glue…Held together with ingenious, invisible paper hinges, the screen can be folded for storage or transportation, resulting in a monumental-size painting light enough to be carried by a single person.”

Numerous screens portray famous shrines, dating from the early seventeenth century, but few pair the two sites of Itsukushima and Wakanoura with each other. In her report to the SBMA Collection Committee, Graham illustrates other known versions of this duo in the Tokyo National Museum, Idemitsu Museum of Art, and the Wakayama Prefectural Museum. Santa Barbara is fortunate to be added to this list of “famous places.”

Prepared for the Docent Council of the Santa Barbara Museum by Letitia (“Tish”) O’Connor, 2025

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goodall, Hollis. Lectures to the SBMA Docent Council, October 3, 2018, and January 20, 2019.

Graham, Pat. Report on “Views of Itsukshima and Wakanoura,” presented to the Collection Committee at the Santa Museum of Art, October 17, 2017.

Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 2018. “Paths of Gold” exhibition labels.

Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Object labels in SBMA galleries, 2024.

Seishi, Namiki. Untitled? article, Bijutsu Forum 21 (33), 2016. (Attached, in Japanese)

Sweeney, Kyoko. SBMA docent website, Oct 2002.