Ellsworth Kelly

American, 1923-2015 (active France)

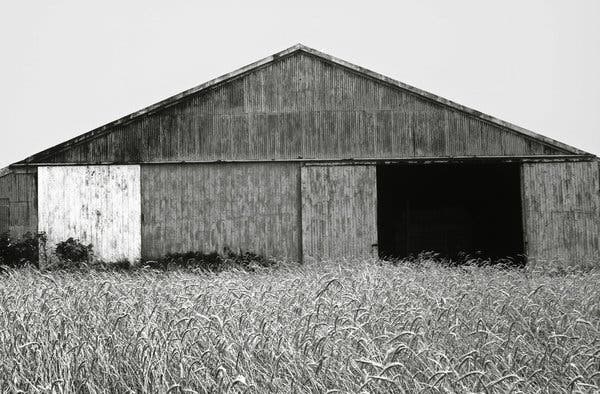

Barn, Southampton, 1968

gelatin silver print

11 × 14 in.

Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, Spencertown, New York

Ellsworth Kelly - Self-Portrait with Thorn, 1947

"I realized I didn't wan t to compose pictures ... I wanted to find them" - Ellsworth Kelly

COMMENTS

Ellsworth Kelly first picked up a camera in 1950 and began making pictures as “records of my vision, how I see things,” he told an interviewer in 1991. His straightforward pictures of houses, barns, brick walls and winter branches yield the same distinctive observation of perceptual phenomena so characteristic of his hard-edge paintings, sculpture and prints: Rectangles float; shadows fall into hard-edge shapes; surfaces reveal evenly mottled patterns and unlikely grids.

Black-and-white photography was tailor-made for these interests. His simple picture of a barn in Southampton, N.Y., for example, is a study in elementary geometry, underscored by the pure black, white and grayness of the photographic print. He divided the picture frame into three precise strips: On top, the gabled roof is a well-balanced triangle; underneath it is a wall composed of squares and rectangles, one painted white, and another a deep-black opening bookended by two gray doors; below is a lighter shade of evenly patterned grass.

Once you see the structural components and the geometric contours, the barn itself seems rather incidental. His photographs show the layered planes of the three-dimensional world as seen by the eye before the mind can identify the objects within it.

Mr. Kelly was interested in the 19th-century photographers Timothy O’Sullivan and Carleton Watkins, both of whom made pictures of vast landscapes that flattened into line and shape; he believed they were “doing things with form that no one was doing in painting.”

“Photography is for me a way of seeing things from another angle,” he said, describing, for example, the way a scene viewed through the spindles of a chair is altered by moving perceptibly in one direction or another. In other words, everything is rearranged depending on how it is framed, and Mr. Kelly explored an endless variety of new arrangements to see how they might reside on the surface of the picture plane.

The shadows, outlines and juxtaposition of elements that preoccupied him are things, he noted, that early man would have seen. They are the visual building blocks that toddlers see as they try to comprehend the vicissitudes of the physical world.

The camera is a neutral device. Edward Weston, who photographed patterns and structures in nature, drew a distinction between making pictures to learn about the world and those that impose a vision upon it. It was his intention to make pictures, he once said, not as “an interpretation, a biased opinion of what nature should be, but a revelation — an absolute, impersonal recognition of the significance of facts.”

It is edifying to look at Mr. Kelly’s photographs with their deadpan fidelity to the actual world, and to be reminded of the purity of the camera in service of the artist trying to understand the perceptual building blocks of his own experience — and of ours. “I realized I didn’t want to compose pictures,” he told The New York Times in 1996. “I wanted to find them.” And he did.

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/25/arts/design/review-the-painter-ellsworth-kellys-love-affair-with-photography.html