Alexei Jawlensky

Russian, 1864-1941

Sorrow, 1928

oil wax medium on cardboard

16 1/8 x 12 1/2 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert B. Baird

1967.11

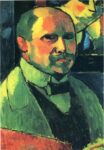

Sergei Jawlensky - Self-Portrait, 1928

“Human faces are for me only suggestions to see something else in them – the life of color, seized with a lover's passion.” - Alexei Jawlensky

“I knew that I must paint not what I saw, but only what was in me, in my soul.” - Alexei Jawlensky

RESEARCH PAPER

Alexei Jawlensky (1864-1941) is regarded as one of the great German Expressionistic portrait artists, and yet, ironically, he was born and raised in Russia and did not consider his images of faces to be portraits. To him they were meditations on mystical and spiritual concerns. As he once remarked, “For me the face is not just a face but the whole universe. In the face, the whole universe is revealed.” (Heather Hess, German Expressionism: Works from the Collection. 2011).

Highly impressionable and eager to learn, frustrated with the Realistic Movement in the late 19th Century, Jawlensky moved to Munich from Russia in 1896 and was heavily influenced by the number of new “isms” brewing in Europe: Fauvism (the wild beasts)—in particular the artist Matisse, (Jawlensky was sometimes referred to as the “Russian Matisse”); and the Constructivism and Cubism of Kadinsky (who became a lifelong friend.)

Matisse introduced Jawlensky to the spiritual Nabi movement. Les Nabis (the prophets) were a group of artists who eschewed realism and instead encouraged the expression of spiritual truths through their art. He also joined the Neue Künstlervereinigung (“New Artists’ Association”) eventually gravitating toward an offshoot group, “The Blue Rider” led by Kadinsky which promulgated “…forms which must be stripped of all extraneous to express strongly only what is necessary.” (Kadinsky)

Starting from 1917, Jawlensky worked on three series: Mystical Heads, 1917-1921, Geometric Heads, 1921-1933, Meditations, 1933-1937—wholly focusing on the human face. This leads us to ‘Schmerz’ (Sorrow), an oil wax on cardboard painted in 1928, one of over 300 paintings in the “Abstract Heads” also known as the “Geometric Heads” series. The series is reminiscent of the geometric figures of Cubism with contoured horizontal and vertical lines filled with vivid panes of color. The linear structure of all the works in the series is basically the same: an asymmetrical and strikingly simple composition of faces with the eyes closed. The only variation being Jawlensky’s play with color.

Without question, ‘Sorrow’, is steeped in sadness. The long contour line of the nose bifurcates the painting; connects with the right brow; the angle continues upward forming a triangle— perhaps a sail—then travels south completing the left, downturned eyelid. The half circle of the chin mirrors the curve of the eyes and the lobe of the right ear. The composition of the face, to this viewer, resembles a sailboat bobbing on turbulent waters—with the chin the hull of the ship. One worries soon to be a sinking ship.

Deeply spiritual, grounded in his Russian Orthodox roots, Jawlensky depicts religious overtones with the stained-glass palette of reds, yellows and blacks. Matisse and the Fauvist influence are most certainly on display with the bold colors and texture. The yellow and red tones, with their haphazard-like brush strokes, weigh heavily as if color is literally being drained from the face. The top of the head is missing—perhaps consumed by the looming, pale-gray background. We can’t help but feel despair when observing, yet perhaps, the last vestige of hope is suggested with the gentle, calming coral pastel of the bottom lip; the tip of the lobe; above the brow.

In the late 1920’s, Jawlensky was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis—about the time he painted ‘Sorrow’ and became increasingly debilitated. Initially affecting his hands, it made it almost impossible to hold a paintbrush and he had to use both hands to paint. With the extreme pain he must have experienced, one can’t help but wonder if the title of this painting, the sentiment expressed, sorrow, is sadly, somewhat autobiographical. Arthritis eventually paralyzed Jawlensky and forced him to abandon painting in 1938.

Adding to his physical difficulties, in 1933, the Nazi’s banned Jawlenky’s paintings labeling them as “Degenerate Art”: the Nazi regimes’ perverse program criticizing and ostracizing modern art. Jawlensky was forbidden to show any of his work and in 1937 the regime went even further confiscating many of his oils to display in The Degenerate Art exhibit in Munich.

Alexei Jawlensky died in 1941 at the age of 77. Most of his paintings are now held at the Museum Wiesbaden in Germany. Having had created over 2,000 oil paintings of the human face—self-described as acting as the mirror of his soul, Jawlensky accomplished what he was after—expressing what was churning within, saturated with his passion and spirituality all within the confines of a face.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Judith Dewey, January, 2023

Bibliography

Goldberg, Itzhak. Jawlensky The Promised Face (French Edition). Editions L'Harmattan.

https://cartedart.wordpress.com/2015/05/12/alexej-von-jawlensky-meditation-verhaltene-glutsubdued-glow-n-112-february-1935-private-collection/

https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-4983628

https://davidcharlesfox.com/alexej-von-jawlensky-abstract-heads/

https://www.landaufineart.ca/jawlensky

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/02/27/the-beautiful-and-the-unexpected

https ://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/09/arts/design/from-alexei-jawlensky-abstract-faces-at-fullintensity.html

https://www.studiointernational.com/alexei-jawlensky-neue-galerie-review-new-york

http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/famous-artists/alexei-jawlensky.