Awol Erizku

American, 1988-

Nefertiti - Miles Davis (Gold), 2022

hard coated foam and mirrored tile, ed. 1/5

SBMA, Museum purchase with funds provided by the Gail Wasserman Family Foundation and the Luria/Budgor Family Foundation

2022.215.1

Awol Erizku Photo by David Alekhuogie, courtesy the artist and Gagosian Gallery

“Part of my studio practice involves spending over two hours a day finding new music so that when I’m in the studio I have something to play, something new to work off of. So yes, it’s crucial to my work.” - Awol Erizku

RESEARCH PAPER

“Nefertiti - Miles Davis” is golden, mirrored, mosaic sculpture of Nefertiti that spins from the ceiling with light and music. A multi-disciplinary installation, it projects spots of light on the walls and was designed to be played to the rhythm of Miles Davis’s album “Nefertiti.”

Awol Erizku’s art is built on his strong African roots. Nefertiti was an iconic 18th Dynasty Egyptian Queen. In his works that include Nefertiti, the historical strength of Black culture is underscored by the world power of ancient Egypt, and the international recognition of Queen Nefertiti.

A Styrofoam sculpture covered by numerous, small, gold, square mirrors, “Nefertiti - Miles Davis” is reminiscent of disco balls popular in the 1970’s. The recorded mixtapes of the Disco Era combine Black R&B, soul, jazz and rock, and Latin sounds like salsa. Mixtapes have become an important part of Erizku’s artistic inspiration and practice.

Erizku’s objective is to move Black cultural representation out of a European context. He breaks the boundaries and traditional conceptions of art and culture by referencing and exploring an expansive Black imagination. Bridging the gap between an African and an American culture, Erizku builds an aesthetic he sometimes calls “Afroesotericism.”

He does not distinguish between commercial and fine art. In an earlier piece, “Nefertiti (Black Power)” (2018), Erizku depicts Nefertiti in glowing neon. The image of the African Queen includes Chinese characters that translate in English to the words “Black Power.” The neon suggests popular culture and advertising, particularly as it is seen in Hong Kong where he first showed this piece.

A surrealist, a satirist, and an appropriator from the school of Duchamp (whose 1917 “Fountain,” was a commercial urinal), Erizku has stamped Black Panther symbols on American flags and spray painted them on white picket fences. He collects and repurposes found objects for his art and is interested in the relationship that Black people have to iconography in fashion, style, and beauty.

Art need not be confined by or limited to museums, galleries, or concert halls. Erizku believes art can and should be shown in public spaces, including those previously reserved for advertisements. He has shown 600 photographs in New York City and Chicago bus shelters, which have become transformed into enclosed glass showcases for art. These enclosures have traditionally been reserved for advertisements.

He sees social media as a vehicle for expanding both access to and definitions of what is considered art. Erizku has talked about how his childhood engagement with television and the Internet opened the world to him, enabling him to discover unexpected points of cultural continuity.

A prolific photographer, sculptor, painter, filmmaker, and DJ, Erizku’s art is most often multi-disciplinary. His ethos is poetry. Collage and mixtapes have inspired his technique. His use of color, light, movement, shape, staging, and music is designed to enhance the strength and beauty of his Black subjects.

Erizku thinks of himself as a visual “Griot,” the West African storytellers who are the keepers of oral history. He hopes to preserve Black expressions of music as an art form by giving them a visual component. His spirituality, poetic ethos and dual Ethiopian and American heritages give him a unique kind of artistic vision.

Born in 1988 in Ethiopia, Erizku grew up in South Bronx, New York where he attended Art and Design High School. In 2010, he received B.F.A. from Cooper Union and four years later his M.F.A. from Yale’s Visual Arts program. While college and graduate school expanded his skills and knowledge of the arts; it also confirmed his growing recognition that people like him tended to be invisible in the art world.

He has described his mother as a “closeted poet,” who refused to publish anything. Talking in parables she avoided giving him direct answers, allowing him to come to his own conclusions. He has said that his mother’s way of thinking has very much influenced how he thinks, how he does art, and why he believes that art can spark an idea of what is possible.

Erizku intention is to influences how Black culture is represented. He uses global/cultural references to reclaim and repurpose the subjects and artifacts of history that have previously been seen through colonial and post-colonial lenses.

In summary, Awol Erizku breaks boundaries, changing both how art is defined and how it is disseminated. His art is multi-disciplinary, multi-cultural and international. It does not distinguish between commercial and fine art. It moves away from a European context, exploring the consciousness, emotion, and imagination of a Black cultural esthetic. He advocates for his work to be shown in commercial spaces and on social media as well as in more traditional art venues. Awol Erizku has built his art on the foundation of artists that came before him; it is appropriated and, it is entirely original.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Sheryl Denbo, 2024.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bailey, Stephanie. “Awol Erizku’s Global Afropolitism.” OCULA, March 9, 2022 (online).

Duron, Maximiliano. “At Gagosian, Awol Erizku Takes Apart the Sphinx to Offer New Possibilities for Imagination.” ARTNEWS, March 11, 2022.

Erizku, Awol, director “Chadwick Boseman: Portrait of an Artist.” 2021 (short film).

Erizku, Awol. “Mystic Parallax.” 2023.

Rea, Naomi. ‘I’m Not Giving People What They’re Used To:’ Artnet interview, February 1, 2023.

Sargent, Antwaun. ‘Awol Erizku Is Creating A New Language,’ GO. October 1, 2020 (interview on-line).

St. Felix, Doreen. “Awol Erizku’s Afro-esotericism.” The New Yorker, June 7, 2023.

Tyner, Ashley. “Artist Awol Erizku, On Creating New Black Mythologies.” March 11, 2022 (online).

POSTSCRIPT

The Santa Barbara Museum of Art is home to three of Erizku’s works: 1, “Nefertiti - Miles Davis,” 2022, (discussed above), is an installation designed to combine music, light and motion with a sculpture of Nefertiti; 2.“No Hesi,” 2022, 97” x 72", mixed media painting, on aluminum, made with spray paint, metal chains and two regulation size basketball hoops. Erizku produced a conceptual mixtape to score the exhibition where this painting was originally shown; 3. An untitled, 2021, life size photograph of Amanda Gorman, a Black American poet and activist. Gorman, born in 1998, became the first person to be named National Youth Poet Laureate in April 2017.

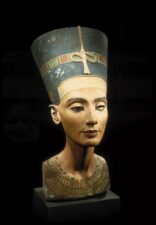

Thutmose – Queen Nefertiti, ca. 1345 BCE, Neues Museum, Berlin

COMMENTS

Awol Erizku is an Ethiopian-born American artist known for his staged portraits of African Americans and appropriation-based practice. Reminiscent of both David Hammons and Richard Prince, Erizku’s sculptural installations and photography meld canonical Western artworks with assemblages lifted from African culture, gang markings, and vernacular objects. “I treat my Instagram account like a gallery—I keep it private and then from 9 to 5, Monday or Tuesday through Friday, like gallery hours, that’s when it’s public,” he said of his approach to creating art. “It’s in line with what I do anyways, which is kind of like using readymades in the 21st century.” Born in 1988 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, he grew up in the Bronx neighborhood of New York before attending Cooper Union where he graduated in 2010. Receiving his MFA from the Yale School of Art in 2014, the artist had his first solo exhibition the same year “The Only Way is Up” at Hasted Kaeutler gallery in New York. In 2017, it was discovered that Erizku was behind the famous photographs released on Instagram of Beyoncé, first several months pregnant and later posed with her twin infant sons. The artist currently lives and works in Los Angeles, CA.

http://www.artnet.com/artists/awol-erizku/

Since its discovery in the early 20th century, the bust of Nefertiti, a work of limestone and stucco crafted by the sculptor Thutmose around 1345 B.C.E., has cemented the ancient Egyptian queen’s relevance as a global pop-culture icon. The Nefertiti of the infamous sculpture dons her signature cap crown, an extravagant royal blue headdress with a golden diadem band and elaborate designs, which suggest a power embellished by an elegant aesthetic. Beneath it, her face—symmetrical, poised, and objective in its beauty—is a reminder of the allure that has made the bust of Nefertiti one of the world’s most enduring artworks.

A testament to her staying power in popular culture, Nefertiti’s likeness continues to be reimagined by contemporary artists around the world. Through their adaptations and homages, these artists’ works bridge the gap between antiquity and modernity. Yet the sculpture is also the subject of heated debates; the significance of Nefertiti’s gender and questions surrounding her racial identity have forged schisms in her modern cultural appeal. Over the past few decades, German, Egyptian, and American artists, in particular, have pushed matters of race and gender to the forefront of the discourse surrounding Nefertiti, calling on us to consider what it means to co-opt, distort, and reimagine the image of an African queen to whom many feel entitled…

In his numerous works featuring Nefertiti, Ethiopian-American artist Awol Erizku argues for Nefertiti’s utility as a historical reference point for black cultural dominion and extravagance. In Nefertiti (Black Power) (2018), the profile of the Egyptian queen is lit up with neon lights. As a medium that doubles as an advertising tool, neon lights are often used to intrigue consumers. This neon Nefertiti denies the viewer eye contact, drawing us in while keeping us at a distance. In Nefertiti—Miles Davis (2017), Erizku continues to connect Nefertiti with black culture, this time by transporting her to the 1970s, disguised as a disco ball.

For all the lore that surrounds Nefertiti’s image, very little is known about the life of the “beautiful one,” as she is called. In fact, Nefertiti largely disappeared from the historical record by the 12th year of her husband Akhenaten’s reign, when she was around 30 years old. Yet as an ancient muse, her cultural potency is only enhanced by this mystique. Without it, she would not be fit for the artistic and political projection that remains foundational to her posthumous reception. By inciting our engagement with the politics of race, gender, and colonial entitlement, Nefertiti has effectively surpassed the royal reach that once marked her dynasty. In exchange for this influence, she must remain a figurehead, her 21st-century fame marked by the disembodied power of a bust.

- Jordan Taliha McDonald, How Nefertiti Became a Powerful Symbol in Art, Feb 16, 2019

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-depictions-nefertiti-way-society-views-gender-race

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

At one level, this is a golden disco ball with lights traveling across the floor, a sparkling but silent evocation of the disco era and dance clubs. On another, it is the iconic portrait bust of Nefertiti (1345 BCE), an ancient Egyptian queen, and contains layered references to Black history and identity. Because ancient Egypt was a world power and an African country, it looms large in the consciousness of Africans and African-American people today as a respected and consequential Black nation. There is still more to unpack. First, Miles Davis’s album Nefertiti (released 1968), which turned out to be the trumpeter’s final all-acoustic recording. Second, the decision to make a golden mirrored mosaic that rotates with spotlights, reintroducing the timing, rhythm, and movement of the album.

- State Street Entrance, 2022