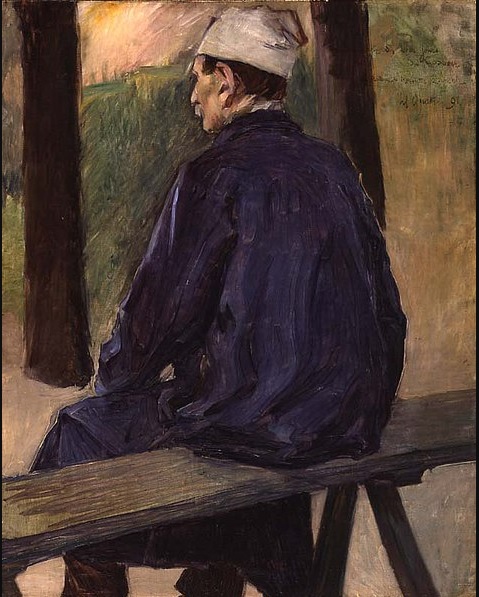

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

French, 1864–1901

A Convalescent, 1891

oil on canvas

31¾ × 25½ in.

Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio, Museum purchase, Howald Fund

Louis Anquetin - Portrait of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1886

"Lautrec has an excellent portrait of a woman at the piano ["Mademoiselle Dihau at the Piano", 1890, Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Albi] and a large painting which holds its own very well. ["At the Moulin Rouge: The Dance", 1889-1890, Philadelphia Museum of Art] There’s a great distinction in it, despite the risqué subject. In general it’s noticeable that the public is beginning to be more and more interested in the young Impressionists, there are at least a certain number of art lovers who are beginning to buy them."

- Letter from Theo to Vincent, 19 March 1890

COMMENTS

Vincent Van Gogh (1853-90) and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), eleven years his junior, both contracted syphilis and both died at the age of thirty-seven. Despite their completely different backgrounds, character and way of life, these freakish outsiders formed a strange friendship during the last four years of Vincent’s life. They were drawn together by their passion for art, which relieved the agony of their lives. They respected each other’s work, exhibited together, exchanged paintings and corresponded, though none of their letters has survived.

Vincent, the son of a Protestant minister, grew up in a dreary Dutch village. He had abortive careers as an art dealer, schoolteacher, bookseller, magazine illustrator, clergyman, and evangelical missionary among Belgian coal miners, and for years lived alone and impoverished in rural villages. After painting peasants and briefly studying at the Antwerp Academy, he moved to Paris to live with his brother Theo, an art dealer, who gave him psychological and financial support.

Lautrec was born in Albi, in southwest France near the Pyrenees, into a wealthy and disastrously inbred aristocratic family. He grew up on their inherited estates—his father a great sportsman, his mother frail and indulgent—and was educated at the elite Lycée Condorcet in Paris. He broke both legs in two adolescent accidents and grew to be only four feet, eleven inches tall in Cuban heels. The worldly and sophisticated Lautrec had a defensive razor-sharp wit and confessed, ‘my family has done nothing for centuries.’

Vincent’s blunt peasant features were disguised by a striking red beard. Lautrec, severely disabled and grotesquely ugly, could not hide his deformity and lurched along on crutches, lisping and drooling. The singer Yvette Guilbert, whom he painted, was shocked on encountering his ‘enormous dark head, red face and very black beard; oily, greasy skin; a nose that could cover two faces; and a mouth like a gash from ear to ear, looking almost like an open wound!’

They met as students, learning the basic skills of drawing and painting, in the studio of Fernand Cormon. The French critic Marc Tralbaut writes,

Cormon, who was described by Toulouse-Lautrec as the thinnest and ugliest man in Paris [quite a compliment, coming from Lautrec], had gained a certain reputation from his large historic compositions, which are now completely forgotten. He was an indifferent painter, but he was a good teacher, whose kindness and patience made up for his lack of talent and imagination.

Lautrec’s biographer David Sweetman explains that Vincent was in a precarious mental state: ‘When he arrived at the studio in the autumn of 1886 he was already teetering on the brink of emotional collapse, enervated by the excitement of Paris, obsessed with wild enthusiasms, swinging between delirious happiness and sudden, uncontrollable rage.’ Julia Frey, another Lautrec biographer, describes Vincent’s weird and off-putting behavior:

Often morose and withdrawn, he worked silently in the studio, ignoring the students’ banter, then suddenly breaking into unsettling loquaciousness, engaging anyone near him with abrupt intensity. On those occasions he would launch into stuttering outbursts of bad French, loudly declaiming his theories on line and color, and hissing through badly fitting false teeth.

Vincent could not fit into the studio; Lautrec did not even try.

Their art was as different as their personalities. Vincent worshipped Delacroix; Lautrec adored Degas. Vincent’s jagged brush strokes and vertiginous swirls of paint seemed charged with an electric current; his expressionist art was feverish and agonized. Lautrec’s superb draftsmanship and incisive satire seemed effortless. But both artists believed that the subject of a picture was less important than its execution and that the painter must be committed to an ideal vision of art. Lautrec, one of the first to recognize Vincent’s talent, introduced him to the intoxicating pleasures of absinthe and to the louche cabarets of Montmartre.

Sweetman also explains that Lautrec was perversely attracted to the boorish qualities in Vincent that repelled everyone else—and this enabled him to break through Vincent’s protective carapace:

He found Vincent’s gaucheries and wearisome habits of alienating everyone appealing, for he too had suffered from public aversion to his appearance. The stumpy, black-clad aristocrat with his fleshy face and bulbous eyes peering through his pince-nez, and the emaciated Dutchman in his workman’s blue, with his hunched shoulders and suspicious looks, were soon familiar partners in the bars and cabarets of the Butte.

In a revealing dramatic passage, the model and painter Suzanne Valadon described Vincent’s crude social behavior:

I remember Van Gogh coming to our weekly gatherings at Lautrec’s. He arrived carrying a heavy canvas under his arm, put it down in a corner but well in the light, and waited for us to pay some attention to it. No one took notice. He sat across from it, surveying the glances, seldom joining in the conversation. Then, tired, he would leave, carrying back his latest work. But next week he would come back, commencing and recommencing with the same stratagem.

Unable to take part in the sophisticated talk about art, craving recognition and obsessed with his own work, Vincent couldn’t think of any other way to attract attention to his one-man show. Though the artists teasingly refused to acknowledge his picture, he persisted, week after week, in his hopeless and humiliating ploy.

Believing that Lautrec was very wealthy, Vincent pursued him with idealistic plans for an artists’ commune. Lautrec disliked these schemes and, perhaps impatient with his tedious friend, gave him excellent advice and made a shrewd prediction. He praised the light and color of Provence and thought the brilliant atmosphere in the south of France would inspire him. In February 1888 Vincent left Paris for Arles and began to create his greatest work.

In a reflective letter to Theo of August 11, 1888, Vincent compared his brilliantly coloued portrait of Patience Escalier, a Provençal herdsman and gardener, to Lautrec’s soft and subdued painting of a sad Parisian, ‘Young Woman at a Table: Poudre de Riz’ (face powder), which Theo owned. Patience, with a yellow straw hat, ruddy complexion, grey beard and blue shepherd’s smock, rests his huge rough hands on a tall stick. In Lautrec’s grey-toned painting, the pale-faced woman, with a white blouse and billowing dark skirt, is seated facing the viewer with her arms crossed on the tablecloth and a red jar in front of her. Trying to match Lautrec’s art and his own, Vincent felt the odd association and unusual contrast would make both pictures look more interesting:

I don’t think my peasant will do any harm, for instance, to your Lautrec, and I even make so bold as to imagine that the Lautrec would appear still more distinguished by the contrast, and that mine would gain by the odd association, because that sunlit, sunburned quality, weatherbeaten by the full sun and open-air, would come even more into its own alongside the face powder and the fashionable clothes.

The following year, in another letter to Theo, Vincent again praised his friend’s art: ‘There are some Lautrec’s [sic], which are very powerful in effect, among other things a “Ball at the Moulin de la Galette”, which is very good.’ A mutual friend reported, in contrast to Vincent’s earlier gauche efforts, that Lautrec was now ‘equally attentive to everything Van Gogh showed him. He would take a deep breath, then look and listen. Every time his horizon broadened, he would clap his hands.’

In early l887 Lautrec did a pastel on pasteboard, ‘Portrait of Vincent Van Gogh’. He exchanged it for one of Vincent’s works and it is now in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. Vincent is seated at a table with a tall glass of cloudy absinthe in front of him, which probably accounts for his tense feeling. This highly alcoholic, anise-flavored, green-colored spirit, though not (as claimed) hallucinogenic and addictive, was banned by 1915 in most European countries. In ‘Poison’, Charles Baudelaire glorified the sublime effects of the ‘green fairy’: ‘Nothing can equal the fearsome marvel of your acid saliva, which plunges my remorseless soul into oblivion and, bringing vertigo, swirls it in a swoon to the shores of death.’

Vincent, seen in profile, with a high-arched nose, jagged red beard, blue shirt and brown jacket, leans forward with clenched hands and a fervent expression. Behind him is a blue zinc table with empty glasses, a six-panelled window and a swirl of yellow lines that suggest the effects of the absinthe. Frey notes that Lautrec imitated Vincent’s ‘multicolored hatching and comma-like strokes’ to portray his anxious mood. Gazing straight ahead and lost in thought, Vincent may not have posed for this portrait but been caught in a moment of reflection or despair.

Lautrec confirmed his friendship with the absent Vincent in a drunken banquet in January 1890. He got into a violent dispute with the mentally unstable Belgian painter Henry de Groux—like Lautrec, a Velázquez dwarf—who insulted Vincent’s work and called him an ignoramus and a show-off. The two miniature men almost came to blows as Lautrec’s friends tried to keep him from demanding a duel. The dispute ended when the painter Paul Signac threatened to kill de Groux if he hurt Lautrec.

The last meeting of Vincent and Lautrec, who was an unexpected guest, took place at Theo’s Paris flat on July 6, 1890. The two friends, so often the targets of mockery, were delighted to find someone else to mock. They had a lot of fun at the expense of an undertaker’s assistant they had just met on the staircase. Vincent was in unusually good spirits, and four days later told Theo, ‘I have very pleasant memories of this trip to Paris. The picture by Lautrec, the portrait of a woman playing the piano [“Portrait de musicienne”], is very remarkable. I was deeply moved by it.’

On July 27, only three weeks after their last meeting, Vincent shot himself in Auvers, outside Paris, where he was being treated by Dr Gachet. On July 31 Lautrec, who heard the news of Vincent’s death too late to join the cortège at his funeral (he was too short to be a pallbearer), sent his condolences to Theo and reaffirmed his comradeship with Vincent: ‘You know what a friend he was to me and how anxious he was to prove it. Unfortunately, I can acknowledge all this only by shaking your hand cordially in front of a coffin, which I do.’

- Jeffrey Meyers, The Madman and the Dwarf: Van Gogh and Lautrec, The London Magazine, June 7, 2021

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Toulouse-Lautrec first met Van Gogh in the studio of Fernand Cormon, where both artists studied, along with their mutual friends Louis Anquetin and Émile Bernard. Lautrec was fascinated by the demi-monde social ‘types’ that he observed in Montmartre, which abounded in dance halls, circuses, cafés-concerts, and brothels. The aristocrats, streetwalkers, artists, writers, models, and cancan dancers he counted among his friends became the subjects of his art.

As is frequently the case in Lautrec’s work, the main figure (a recovering patient) is shown as though unaware of being watched, while seated on a park bench, presumably taking the fresh air as a restorative to good health. Lautrec’s ill health (he suffered from an undiagnosed bone disorder that stunted his growth) and terminal alcoholism would result in his own status as a recovering patient in an asylum in Paris, where he was confined in 1899. Important to note is Lautrec’s interest in representing solitary figures either lost in reverie or seemingly idle, a kind of slowed experience of time that is distinct from the Impressionists’ interest in the rapid flux of modern life.

- Through Vincent's Eyes, 2022