Pablo Picasso

Spanish, 1881-1973 (active France)

Portrait of Dora Maar (Theodora Markovich), 1936

lithograph

35 ¼ x 25 in.

SBMA, Unknown Donor

00.53

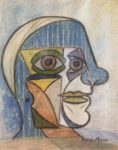

Dora Maar - "Portrait of Pablo Picasso", 1936, Pastel on paper

"Are we to paint what's on the face, what's inside the face, or what's behind it?" - Pablo Picasso

“Everything you can imagine is real.” – Pablo Picasso

RESEARCH PAPER

Pablo Ruiz Picasso left behind a body of work of over 40,000 pieces and a legacy that describes him as one of the most important artists of the 20th century. He spent his life in search of new artistic ways to express himself, continuously combining his ideas with radical innovation. With unprecedented inventiveness he presents his oeuvre in new and unexpected ways, always lively, multi-facetted and stimulating and yet objective. His subjects were women, harlequins, flamenco guitars, peace doves and black bulls, in many media. Whatever his eye captured is inspired by Picasso’s irresistible charisma.

Picasso’s work is never boring nor predictable because of its myriad and surprising content. His original lithographs are among the most brilliant works in his artistic oeuvre, and “Portrait of Dora Maar” is no exception. Picasso himself was rather involved in his lithograph process as he enjoyed improving upon it, and his art, by adding different colors or mixing up materials.

This portrait of Dora Maar, which is executed with Picasso’s very personal style of simple lines, captures the essence of the woman. She holds her head pensively, one eye looking in a different direction, the other eye straight ahead. The expressive, abstracted way of portraying his muse allows us to see her beauty and personality as she is lost in thought. Picasso invites us to see what he considers important. The colors are subdued and pale in this rendition compared to his usual style of painting in vivid colors. Picasso’s style used contoured, linear, figurative outlines without feeling compelled to represent the exact specifics of the subject.

Picasso met Dora Maar (née Henriette Theodora Markovíc) in 1936 at the Café des Les Deux Magots in cafe in Paris where he used to go after his evening walk. He was having dinner with his friend, Paul Eluard, the French Surrealist poet, when Dora’s and Pablo’s eyes met. Picasso later told the story of their meeting. He recounted that Dora was wearing black gloves embroidered with roses that evening. She entertained herself by stabbing spots with a knife between the fingers of her left hand lying on the table. At one point she slipped a fraction of an inch. He mumbled a few words in Spanish which Dora understood since she had grown up in Argentina. They connected instantly and she became one of his many muses. Picasso kept her bloodied gloves all his life in a shadow box.

Dora Maar was an extremely talented surrealist photographer in her own right. However, she abandoned photography after she met Picasso, who encouraged her to paint instead. According to Picasso, she was a nervous and troubled creature. Consequently, he often chose to represent her with large deep eyes full of anxiety, grief, or in a dream-like state. Picasso had six muses over his long life. His relationship with Dora Maar lasted about 10 years. Dora Maar’s presence in Picasso’s life left an indelible mark on the work he produced during the prolific years of World War II. She was intellectually and emotionally challenging. Consequently, he often represented her through torturous imagery, deconstructed angular forms and intense colors. Dora Maar’s jealousy regarding Marie-Therèse Walter and Françoise Gilot finally led to the dissolution of the duo’s relationship. She suffered a nervous breakdown and underwent many years of psychoanalysis. After that she found solace in Roman Catholicism, from which her famous declaration derives — “After Picasso, Only God”. She died in 1997, outliving Picasso by 24 years.

Research paper prepared for the Santa Barbara Docent Council by Gisela Balents, 2020

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Dora Maar”

https://www.pablo-ruiz-picasso.net/theme-doramaar.php

“Masters of Printmaking: Pablo Picasso and His Original Lithographs”

http://news.masterworksfineart.com/2018/02/22/masters-of-printmaking-pablo-picasso-and-his-original-lithographs

“Picasso Printmaking Techniques”

https://sapergalleries.com/PicassoPrintmakingTechniques.html

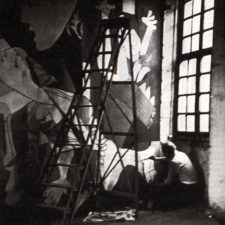

Picasso in production of painting Guernica, photo by Dora Maar.

COMMENTS

In 1936 54-year old Picasso met Yugoslavian Dora Maar (1907 -1997), the photographer who documented Picasso's painting of Guernica, the 1937 painting of Picasso's depiction of the German's having bombed the Basque city of Guernica, Spain during the Spanish Civil War. She became Picasso's constant companion and lover from 1936 through April, 1944. Maar went back to painting and exhibited in Paris soon after Picasso left her for Françoise. Picasso referred to Dora as his "private muse".

Dora Maar and Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso had a string of muses, mistresses and lovers throughout his long career. Yet, there are few who compare, in terms of significance and influence, to Dora Maar. Her relationship with Picasso lasted over a decade, and during this time she was a source of inspiration, an archivist, and assistant, and later a worthy opponent when their relationship soured.

Maar was born in Paris in 1907 to a French mother and a Croatian father. She was christened Henriette Theodora Marković, a name she would later change. Her father won a commission for the Austro-Hungarian Embassy in Buenos Aires, and when Maar was three the family moved to Argentina to allow her father to work on the embassy and other projects. During her time in Argentina, Maar learned French, English and Spanish. However, she was never happy there, disturbed by a sense of isolation, and by her parents’ constant fighting. She returned to Paris at the age of 19, and enrolled at the Académie Julian (the then equivalent of the all-male Ecole des Beaux-Arts). It was during this time that she changed her name to Dora Maar. She studied photography at the Academie, and first met Picasso when she was 28 whilst working on set for Jean Renoir. Unfortunately, Picasso has limited recollection of this encounter, as he recalls a more dramatic meeting, which happened a short time after at Les Deux Magots. Maar was sitting at a nearby table, wearing black gloves embroidered with roses, playing a variant of ‘five finger fillet’, a game in which the player splays the fingers of one hand on a table and then uses their other hand to rapidly and repeatedly stab a knife in gaps between their outstretched fingers. Picasso was instantly enchanted, and even went so far as to ask for her bloodstained gloves as a memento.

Over the following years, Maar became an integral part of Picasso’s life. She found him his attic studio at 7 Rue des Grands Augustins, and helped him move. It was here that she would document and aid Picasso in the creation of his masterpiece Guernica. Maar was the only assistant Picasso worked with on the painting, and the photos she took of Picasso at work are the only ones which remain.

Yet their relationship, though so intimate, was far from perfect, and its many faces and shifting tides are captured in the portraits from this era. Early on, Picasso painted her with an almost comic air in Portrait of Dora Maar, in which she perches, smirking, on a branch as a bare-breasted owl.

Later that year, he painted Maar as the Weeping Woman. The work is often viewed as the conclusive part of Picasso’s study of suffering, which he first began exploring (with Maar as his assistant) in Guernica. Picasso said of Maar:

“For me she’s the weeping woman. For years I’ve painted her in tortured forms, not through sadism, and not with pleasure, either; just obeying a vision that forced itself on me. It was the deep reality, not the superficial one.1“

This somewhat callous description of Maar is important, as it underlines a deep dissonance in their relationship. Theirs was a love coloured by tumult and tension as much as passion and respect. The almost combative blend of the above is best captured in Dora Maar au Chat, 1941, which Picasso painted towards the end of their relationship and during the Nazi occupation of France. The painting depicts Maar in a calm and almost regal setting: she sits atop a throne-like chair, and she wears a hat whose flowers are almost like the tiny arches of a crown. Yet, her hands, which hang loosely over the arms of the chair, are finished with sharp talon-like nails; and the cat, which is curled in her lap has blank, dead eyes, and a gaping maw. The cat was a traditional symbol of feminine sexuality, and its placement and aspect in this painting may hint at Picasso’s merciless shaming of Maar for her infertility. Even during the halcyon days of their relationship, when Picasso called Maar his “private muse”, he continued to see his former lover Marie-Thérèse Walter, and Maya the daughter of Picasso and Walter. When Picasso first laid eyes upon Françoise Gilot in 1943, she was to be Maar’s successor, his relationship with Maar was drawing to a bitter end, and the pair were already beginning to draw battle lines.

Up until the end of both of their lives they were never quite free from the power the other held. Picasso took Dora out for dinner with Françoise to publicly humiliate her by spending the evening extolling the virtues of his new lover, and once again chastising and attacking his former muse. He sent Maar a chair designed to look like an instrument of torture, and in response she sent him a rusty shovel blade. He even had a signet ring engraved with her initials, and then set a large spike at its center to make it unwearable.

Eventually Maar moved to the country, and spent the last years of her life between a small apartment in Paris and her cottage in Provence. She worked on her own paintings, returned to taking photos, and worked on a private collection of poems. She passed away in July of 1997.

1 Léal, Brigitte: “Portraits of Dora Maar”, Picasso and Portraiture, page 395. Harry N. Abrams, 1996.

https://blog.lofty.com/featured/dora-maar-and-pablo-picasso/

Lithograph

Lithographs are made by creating a drawing on a flat prepared surface, usually a large and heavy slab of thick Bavarian limestone. The drawing, made with a greasy crayon or similar material, is then stabilized with a gum-arabic solution. The plate (or flat stone) would then be sponged with water, the greasy drawn areas repelling the water but attracting the rolled-on ink and the rest of the stone remaining wet and repelling the ink. Paper is positioned over the plate, and the pressure of the press transfers the ink from the stone to the paper, printing a reverse image of what was drawn. The dates in reverse in so many of Picasso's prints is due to this fact.

Picasso also created lithographs on zinc plates as they were lighter and did not require him to work at the lithographer's studio. It was 1945 that Picasso took up residence at the Mourlot studio in Paris enjoying the medium where he could rework an image on the same printing surface and preserve the complete evolution of the composition.

Picasso later created his lithographic images on a paper which was then transferred to the stone in reverse from the original drawing. Then, when printed, the print would be a reverse of the inked surface, thereby consistent with the orientation of the original drawing. In examples where Picasso's date is read correctly, it is likely that the print was made by transferring a drawing to the plate.

http://sapergalleries.com/PicassoPrintmakingTechniques.html