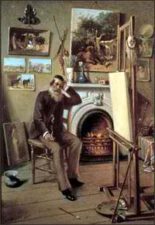

Erneste Etienner Narjot

French, 1826 – 1898 (active America)

The Forty-Niner, 1881

oil on canvas

40 x 50 in.

SBMA, Gift of Marguerite West and Charles King

The Forty-Niner may be thought to be inspired by a very similar painting by another French expatriate painter active in the San Francisco area at the time, Jules Tavernier (above right). While Tavernier’s story in the San Francisco art community is ripe for a full treatment unto itself – he was quite the local Bohemian with a self-styled entourage of his own, suffice it to say he had a dark side as evident his own work detailing the California Gold Rush days, “The Pioneer” (1877; see below), accomplished four years prior to Narjot’s “The Forty-Niner”. It is clear that Narjot’s thoughts of his own Forty-Niner days were less dark than Tavernier’s.

RESEARCH PAPER

What we see is a middle-aged man, a bit scruffy-appearing, seated on his bed in his small, sparse log cabin, with his faithful dog by his side, head resting on his master’s knee. He is reading what we imagine are a collection of letters and other materials from home. Perhaps it has been some months since he has had any news. The title of the piece, “The Forty-Niner”, suggests that he is a lone gold miner in the California foothills seeking his fortune during the California gold rush, as many did at the time. The tools of his trade - a pick, a shovel, and mining pan – are at the foot of his makeshift bed, and right in the front of the composition for the viewer to see. Other necessities of life in the woods are evident in the small room he calls home; an axe and a musket are hanging on the walls. There’s a fire in the fireplace, doubling as his cooking space and also drying his laundry that is hanging from the ceiling. It’s a clean space, although cluttered, but there’s no evidence of the riches he most assuredly was hoping for. There appears to be money lying on the bed that had likely been sent to him in the just-received mail from home. Sunlight is streaming through a window in the back wall, illuminating his face and his letters from home. The artist involves us in the emotions of the 49er by flooding his face with sunlight in the otherwise dim interior. Evident also are the vines creeping in through the open window. Who is this man? Has he been here too long? His countenance, as well as the countenance of his faithful dog, and the presence of the vines creeping in through the window suggest this may be the case. Is he pondering, perhaps, that it may be time to move on?

Narjot was born in Saint-Malo on the northwestern coast of France December 1826, son of a local merchant clerk and his wife, also painters. He studied art at an early age in Paris (school unknown) but at age 23 set sail in 1849 for the gold fields of California to find his fortune, as did close to 30,000 other French pioneers around this time. While he painted on the side during this period, his California mining fortunes did not pan out and, with other disenchanted French miners, he headed to Sonora Mexico at age 26 to start a new mining adventure. While this enterprise also failed, he did meet and marry a young Mexican woman, settled down, started a ranch, bred horses, did some mining, and continued to paint scenes of border life in the area.

Because of the political climate in Mexico at the time, in 1865 at age 39 he returned to San Francisco and opened a studio accepting all commissions in order to survive. He did newspaper and book illustrations, portraits, landscapes, and fresco work, much of it intended for French patrons.

In the 1870s, San Francisco found itself as the financial center for the new-found wealth from the gold fields of California and the silver mines of Nevada, and this wealth turned San Francisco into a “promised land” for artists (Chalmers, 2002). Prosperous patrons began commissioning and collecting art, and Narjot enjoyed much success at this time.

In 1885 at age 59 he found himself teaching art at the California School of Design in San Francisco, exhibiting regularly, including exhibits sponsored by the San Francisco Art Association, the Mechanics Institute, and the California Agricultural Fairs. By the late 1880s, Narjot was considered one of California’s most accomplished painters, earning a gold medal at the 1888 California State Agricultural Fair and a silver medal in the ensuing year.

Narjot was trained in the classic, highly detailed French painting traditions of the time, prior to the introduction of alternative aesthetics, including Impressionism, in the latter half of the 1800s. He is best known for his scenes of the Gold Rush and scenes of border life in early California although he also was active as an accomplished portrait artist. The “Forty-Niner” was painted in 1881, approximately 30 years after his own sojourn in the mining camps in the California gold fields. Could the “The Forty-Niner” be, in fact, a portrait itself, perhaps a self-portrait?

As evident in the Forty-Niner, his portraits often included a dog in the scene (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, n.d.), which, in the context of this painting, would typically symbolize loyalty, faithfulness, and love – perhaps loyalty, faithfulness, and love for his missing family.

The one bright color in this painting, the red flannel shirt hanging on the clothesline, is a bit of a trademark of his paintings of his Gold Rush and border life scenes (Chalmers, 2002) as evident in “The Horses Eagerly quenching Thirst, Camels Disdaining” and “The Search for Water” (both 1867).The use of red is a frequently used artistic device to pull in and involve the viewer in the work.

Narjot died in 1898 at age 72, one year after falling ill from paint or plaster dropping in his eyes while working on an important mural commission on the ceiling of Leland Stanford’s tomb on the grounds of the Stanford University in Palo Alto, CA. As evidence of his stature in the early California art community, thirty well-known California artists at the time held a benefit sale of their works to support Narjot’s family during his illness.

Unfortunately, there a few paintings left by, as he became known, the “Dean of California Painters” (Chalmers, 2002). The great 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire destroyed most of his local commissions, including his very last commission for Stanford University.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Jeff Vitucci, February 2018

Bibliography

Chalmers, Claudine. “The Heart of Bohemia: French Artists in California”. Antiques & Fine Art Magazine. September 2002. Downloaded from http://www.antiquesandfineart.com. November 2017.

Chalmers, Claudine. “Ernest Etienne Narjot (1826-1898)”. California History, Vol. 78, No. 3, Fall 1999; page 146.

Dressler, Albert. “California’s Pioneer Artist Ernest Narjot, A Brief Resume of the Career of a Versatile Genius. 1936. Privately printed. San Francisco.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, n.d. Curator notes for “Portrait of a Girl with a Dog” c. 1879. Downloaded from agency web site https://collections.lacma.org/node/230543

Society of California Pioneers, n.d. “Ernest Etienne Narjot”. Dowlnloaded from agency web site http://www.californiaprioneers.org/collections/art/artists/ernest-etienne-narjot, November 2017

Citations from prior (1979) research paper by Sylvia Jones not cited above:

200 Years American Painting. Cat. 30, Fresno Arts Center, Fresno, Ca. Page 23

American Processional (The Story of Our Country), National Capital Sisquicentennial Commission, Laurel Printing Co., New York, 1950 Pages 143-160

McCraken, Harold, 1952. Portrait of the Old West. McGraw Hill Book Co., Inc. New York, New York..

Ostarnder, Doris, 1974. Artists of the American West. Swallow Press. Chicago, IL.

Narjot, Self-portrait in the Artist's Studio, 1890. Oil on canvas, 38 x 26 inches. Courtesy of Garzoli Gallery.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Narjot made his reputation as one of the leading painters of the California Gold Rush. He arrived in the States from France in 1849, drawn to the prospect of making his fortune by panning for gold. When his luck fell short, he turned to painting as his livelihood, becoming one of the best recognized artists of the Gold Rush, as he had experienced it firsthand. This painting, done decades after his time panning for gold, is overtly sentimental. By the 1880s, the collection of gold was done mechanically, rather than by hand. But this wistful scene of a miner, reading a letter, likely from a faraway loved one, captures the romance of the adventurers who first participated in the excitement of the Gold Rush. The lonely miner lives in a rough log cabin, the simple implement of his vocation, conspicuously on display at the foot of the bed, with only his faithful dog for company.

- Preston Morton Reinstallation, 2022