John Paul Jones

American, 1924-1999

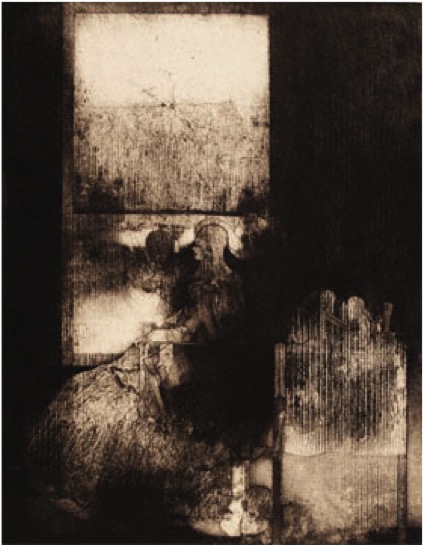

Annunciation, 1959

etching on paper

28 x 22 in.

SBMA, SBMA Acquisitions Fund

1960.22

John Paul Jones. Self Portrait. 1950

“Even taking into consideration the fickleness of art trends, it is surprising to find that in the 1950s and 1960s John Paul Jones was widely and consistently ranked as among America’s leading printmakers,” said art historian Susan Landauer. “In 1963, he was the first pick of the eminent curator Una E. Johnson to inaugurate the Brooklyn Museum’s solo exhibition series on distinguished contributors to the media of drawings and prints in the United States. By then, he had also become a nationally recognized painter. With twenty-eight one-person gallery and museum exhibitions across the country in the first decade of his career, Time magazine gave him an illustrated feature article in 1962. Yet today, Jones has been almost entirely forgotten by art historians–by historians of American printmaking, by historians of West Coast art, and even by scholars writing about the art of Los Angeles, where for many years he was championed as a local talent.”

COMMENTS

John Paul Jones – the visual artist, not the rock bassist – was big in the 1950s and ’60s, known for being one of America’s foremost printmakers.

He founded the printmaking program at UCLA in 1953, and did the same for UC Irvine in 1969. He had dozens of solo exhibitions during his career, including a critical one at the Brooklyn Museum in 1963. Time magazine did an illustrated feature on him in 1962.

But time hasn’t been the kindest to Jones, a Laguna Beach resident from the mid-1960s to 1990. After his death in 1999, he seemed to drop off the map for those documenting California art since the 1950s. Critics and art historians seemed to forget many of his accomplishments in painting, printmaking, sculpture and teaching.

However, a new exhibition at Laguna Art Museum aims to revive Jones’ career and legacy. “John Paul Jones” is a retrospective based on the Laguna Beach museum’s extensive permanent collection of his work – probably the world’s largest. The show, curated by Cal State Fullerton art professor and gallery director Mike McGee, runs through Jan. 23.

The two-gallery exhibit – which incorporates Jones’ prints, paintings and sculpture – comes after a larger exhibition last year at both Cal State Fullerton and Orange Coast College. That show was originally intended for Laguna Art Museum, but didn’t materialize because of lack of funds to mount it and publish an accompanying book on the artist.

Yet, through the hard work of McGee and others, the 210-page text, “John Paul Jones: The Pursuit of Beauty’s Perfect Proof,” has recently been published, providing Laguna Art Museum an opportunity to showcase Jones once again.

“It’s important to have the museum present an exhibition from our own holdings in the collection, which are substantial,” said Bolton Colburn, director of Laguna Art Museum. “That’s why we’re doing this show. With the publication now out, it helps to locate him within the geography of California art and art nationally.”

The exhibit starts with self-portraits, namely the distinctive, black and white etching “Self-Portrait” (1950), then proceeds with mostly figurative prints and paintings. Many of them are quite dark – morose, melancholy and somber in tone and subject matter. An isolated figure disappearing into (or emerging from) a hazy atmosphere of muted color or pure black is a common motif.

Jones’ darkness could be connected to his difficult childhood (his parents divorced and his mother was institutionalized for mental illness), or to his experience as a sergeant in the Army at the Battle of Okinawa during World War II. Historians have identified that battle as one of the deadliest, most grisly encounters in the Pacific theater of the war.

The United States and its allies torched Okinawa’s intricate system of underground tunnels with “liquid fire” (a mixture of gasoline and napalm), and many of those passageways had women and children civilians hiding out in them. Afterward, as a sanitary measure, Jones and his battalion spent three weeks burning corpses. In her essay for the Jones catalog, art curator and writer Susan Landauer cogently articulates Jones’ military past and its possible connections to his work.

“You can see they do have a ghostly quality,” McGee said about Jones’ ethereal, dark works. McGee got his master’s in fine art degree from UC Irvine, where Jones was on the committee judging his master’s thesis. “He was introspective. He was a quiet guy. A modest guy.”

Jones also wasn’t interested in following the flashy trends in the larger art world. As Abstract Expressionism gave way to Pop Art, Jones kept to his discipline of crafting subtle and haunting etchings, lithographs and paintings that weren’t exactly marketable.

“He intentionally avoided being fashionable,” McGee said. Unlike contemporary Andy Warhol, Jones wasn’t obsessed with selling his work or becoming famous. “He was really into challenging himself.”

A CHANGE IN TONE, MEDIUM

After a period of inactivity, Jones got busy in the 1980s with sculptures that mark a distinct departure from his moody, ’60s work. They don’t seem to be affected by disposition, darkness or existential angst. Rather, they are light, energetic, minimalist and diligently hand-crafted.

Pieces like “Harpsichord” (1988) are sparse yet playful, almost musical. Jones created a number of “gate” sculptures from wood and steel which are so finely executed they could nearly be missed by the naked eye. “Jelly Cutter” (1983), made from basswood and aluminum, extends high above the viewer’s head with changing textural values and a bouncy quality that makes it look almost kinetic.

Other pieces such as “Tower 4” (1986) and “Plaza Sweet (Maquette)” (1987) are architectural – mini-towers that could serve as models for future, large-scale projects.

Overall, the sculptures appear as if they were crafted by an entirely different artist. However, some observers say they share the same concerns with line, value and abstraction as seen in his earlier work.

A LEGACY LIVES ON

Though the art historians may have overlooked Jones, legions of his former students remember him fondly. Many of them still live in Orange County or in the greater Los Angeles area. They include McGee of Santa Ana, Irvine artist and curator Jay Sagen, art professor Tom Dowling, and accomplished L.A. artist Ross Rudel.

Dowling, a Costa Mesa resident, studied with Jones at UC Irvine and served as his teaching assistant for two years.

“He was really inspirational to students,” said Dowling, who now teaches art at Orange Coast College in Costa Mesa. “He had this romantic sensibility of what art does, and what the teaching of art is all about. He backed it up with this work ethic. You always knew where John Paul was. He was always in the studio.”

Dowling says he learned many things about the teaching craft from Jones, including “being engaged in a dialogue with students and with ideas. In a sense, not patronizing them, but being there for them at their level.”

Dowling added that Jones encouraged every student to find his or her own voice. “He wasn’t interested in turning out little versions of John Paul. I’ve never met anyone ever who had anything negative to say about their experiences with John Paul as a teacher. He was just a very unique individual.”

Curator McGee says Jones’ work is important to contemporary viewers because it’s complex and layered, yet efficient and minimalist at the same time.

“It’s something that people should see now. In our fast-paced society, there’s a dedication and depth to this that’s becoming very rare.”

- Richard Chang, Orange County Register, November 21, 2010