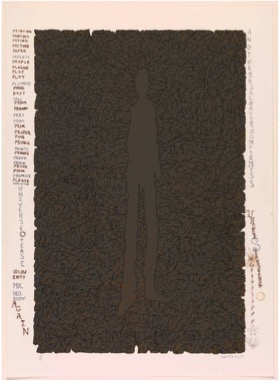

William T. Wiley

American, born 1937

Mr. Nobody, 1975

lithograph

43 x 31 in.

SBMA, Museum purchase, funds provided by SBMA Contemporary Graphics Center and William Dole Fund

1977.27.1

William T. Wiley, 1975 Mimi Jacobs, photographer

COMMENTS

San Francisco Bay Area artist William T. Wiley grew up drawing while listening to cowboy stories on the radio. Now nearly 72 (2009) , Mr. Wiley still sketches while glued to the airwaves.

News and talk shows serve as fodder for many of his word-laced drawings, paintings and sculptures, part of a rambling retrospective at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

While unafraid to take on the weighty issues of the day, the artist often raises more questions than he answers. His densely layered work careens from narrative scenes to enigmatic texts, arcane symbols and clever puns, while juxtaposing different styles and references to earlier art.

What’s that long black diagonal on Mr. Wiley’s watercolor map of the United States? Turns out it represents a highway constructed of radioactive residue from the nation’s nuclear power plants.

Say the title of another work, “Sold Yours Return,” aloud and you’ll get the point. Based on an illustration by N.C. Wyeth, it pictures a homecoming soldier with amputated limbs to symbolize the consequences of war.

Even when you think Mr. Wiley’s intention is clear, another allusion surfaces to complicate the meaning of his stream-of-consciousness imagery. “If it doesn’t stay mysterious, why bother?” he asks rhetorically about his art.

Deciphering “In the Name of (Not to Worry, It’s Juxtaposition),” one of his larger pieces from the 1980s, requires picking out the details in a representational drawing of the artist’s studio framed by snippets of abstract painting. Accompanying the canvas is a watercolor and a sculptural construction, which reappears as part of the drawing.

The piece is rife with references to Mr. Wiley’s earlier works, from an artist’s palette to eyeballs and a four-part square. One of these is the black-and-white line extending across the bottom of the canvas. It alludes to a surveyor’s pole and a scale marker on a map, suggesting the artist is taking his own measure of his work.

More than four decades have passed since Mr. Wiley entered the art scene as part of the Northern California funk movement. At a time when minimalism was in vogue, he and colleagues like ceramicist Robert Arneson jettisoned abstraction for narrative art influenced by popular culture and the conceptual work of artist Marcel Duchamp.

Being outside the mainstream wasn’t always easy for Mr. Wiley. In the late 1960s, he thought of giving up a career as an artist and summed up his feelings in the palette-shaped piece “What’s It All Mean?,” which titles the exhibit.

A trip to Europe inspired him to experiment in watercolor, a traditional medium that liberated his considerable graphic skills. As shown in the exhibit, these delicate paintings resemble old-fashioned book illustrations with patchworks of colored shapes outlined in ink.

In one, “Hide as a State of Mind,” an animal hide resembling a U.S. map is divided by a striped pole into a snowy white East Coast and a colorful interior. A cartoonlike figure in the bottom right corner expresses his exasperation at the regional differences, no doubt a reference to Mr. Wiley’s experiences in the art world.

Unlike many of his single-minded peers, Mr. Wiley has tried his hand at just about every type of art and this fearlessness is part of the appeal of his eclectic work. Within a single piece, he can conjoin contradictory styles and mediums, including folk and high art, abstraction and representation, painting and sculpture.

In addition to working in conventional formats, the artist has dabbled in making hand-colored buttons, an eight-story metal tower and a pinball machine. During a recent lecture at the museum, he sang about the themes of his work while strumming a guitar, a musical instrument represented through several prints and sculptures in the exhibit.

A restless talent whose conflicted feelings about art are discernable in his work, Mr. Wiley pictures himself as “Mr. Unatural,” a tall, lanky figure who wears a fake nose, loosely belted robe and dunce cap. Both magician and clown, the persona is a takeoff on cartoonist R. Crumb’s chunky, bearded wise man, Mr. Natural.

Mr. Wiley also creates characters to poke fun at present-day technology. An artist named “D.V.D.,” a cousin to an earlier figure called “Seedy Rom” (CD-Rom), struts into the foreground of a 2005 painting carrying canvases bearing drawings of sailing ships.

This reference to Christopher Columbus, a recurring theme in the artist’s work, is supported by other imagery related to discovery, including tents inscribed with “Clue us” and “Lark” (Lewis and Clark).

Other recent work reveals Mr. Wiley’s interest in medieval art. To express his outrage over the nuclear meltdown in Chernobyl, the artist enlarged a detail from “Temptation of St. Anthony” by Hieronymous Bosch into a striking painting of a burning village, one of the more straightforward scenes in the show.

In another work, he combined Pieter Bruegel’s “Tower of Babel” with a Mesopotamian ziggurat and a Civil War ship, the Monitor, to represent a construction symbolizing surveillance.

Only a few years ago, Mr. Wiley’s 1960s-style rants would have seemed tired, but in light of current environmental and security concerns, they are relevant again. The artist’s combinations of language and images are right at home in the Internet age, allowing viewers to surf their frames to find wisdom, humor and beauty among his intense ruminations.

By - The Washington Times - Sunday, October 11, 2009